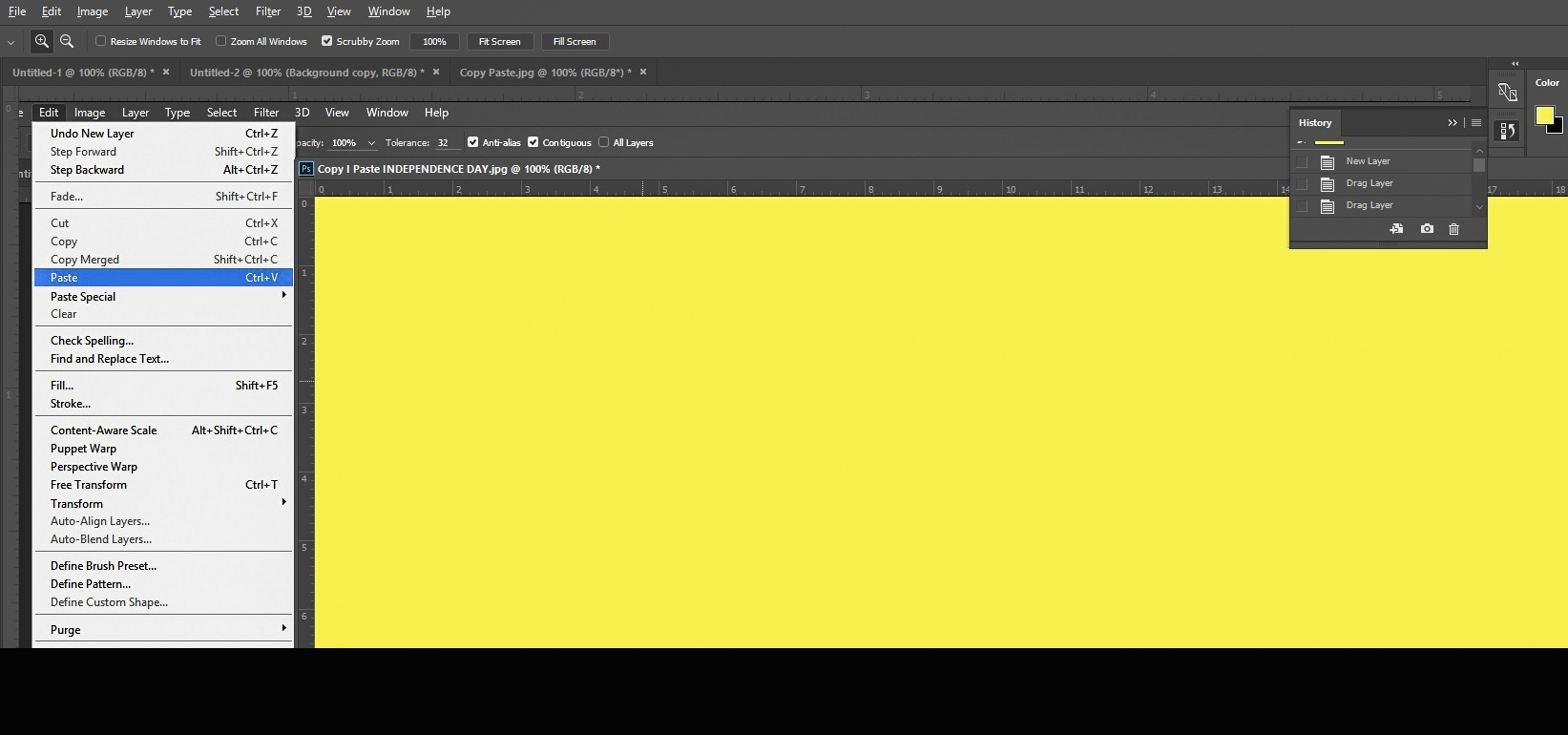

‘Copy paste’ Independence Day

As Kosovo marks another Independence Day, it has many familiar problems — but it can start to move beyond them if citizens are placed at the heart of the country’s democracy.

‘Fake news’ and ‘alternative facts’ might be more recently coined terms elsewhere, but their existence as concepts are not necessarily novel in Kosovo.

Citizen-focused issues have rarely dominated or become the focal point of our daily political conversations.

Besa Luci

Besa Luci is K2.0’s editor-in-chief and co-founder. Besa has a master’s degree in journalism/magazine writing from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism in Columbia, U.S..

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.