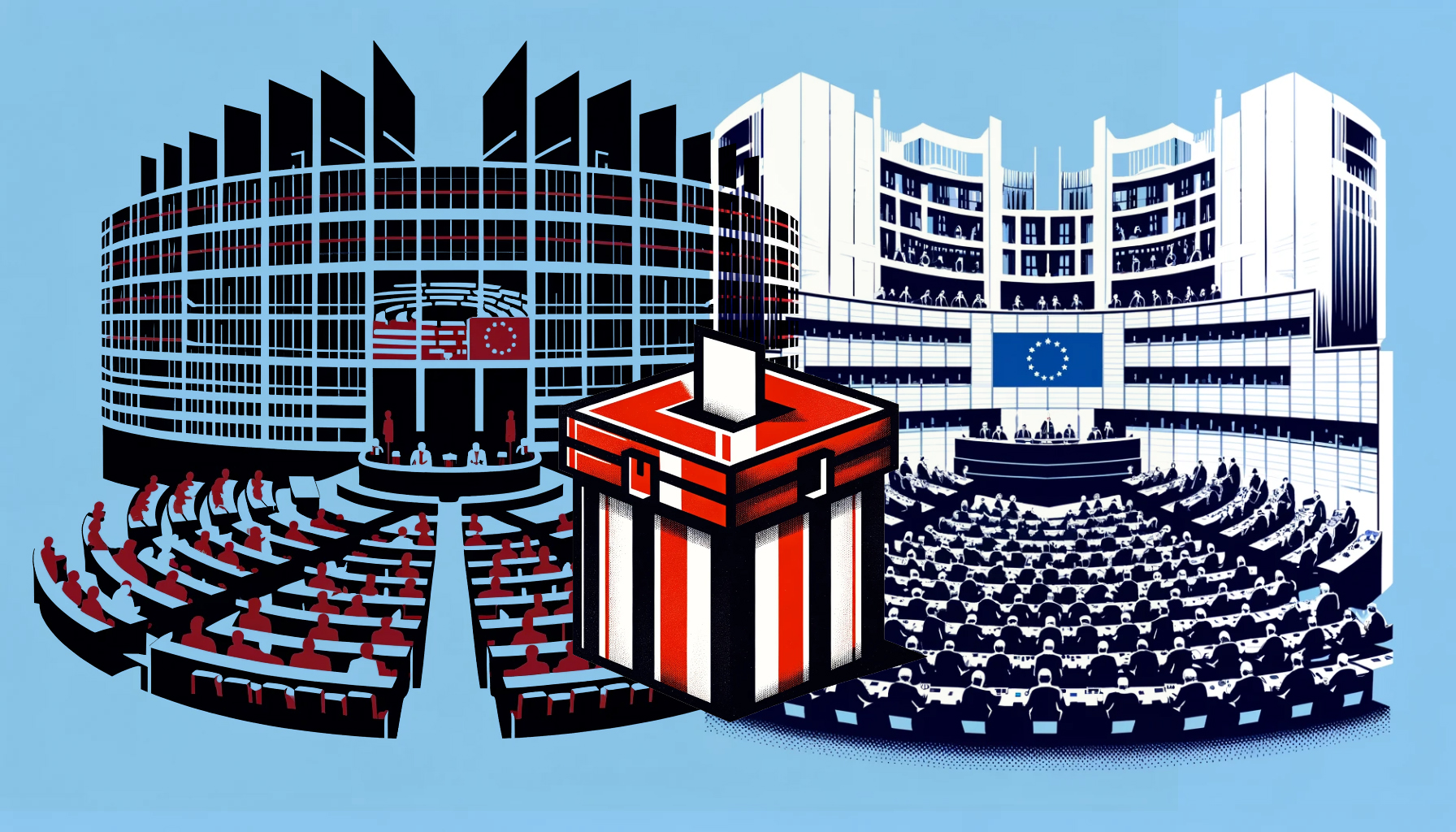

EU voters are normalizing the far right

The left is failing to attract disaffected voters.

What happens when voters elect populists who equate majority will with moral good?

Growing inequality and economic insecurity have created a fertile ground for insurgent political parties to make inroads among voters whose concerns have not been assuaged by mainstream political parties and other political alternatives.

Discourse about far-right parties reflects the political establishment’s unending sense of self-importance.

Nicholas Kulawiak

Nicholas Kulawiak is English language editor at K2.0. He holds a master’s degree in Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies from Georgetown University and bachelor’s degrees in History and Politics from University of Puget Sound.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.