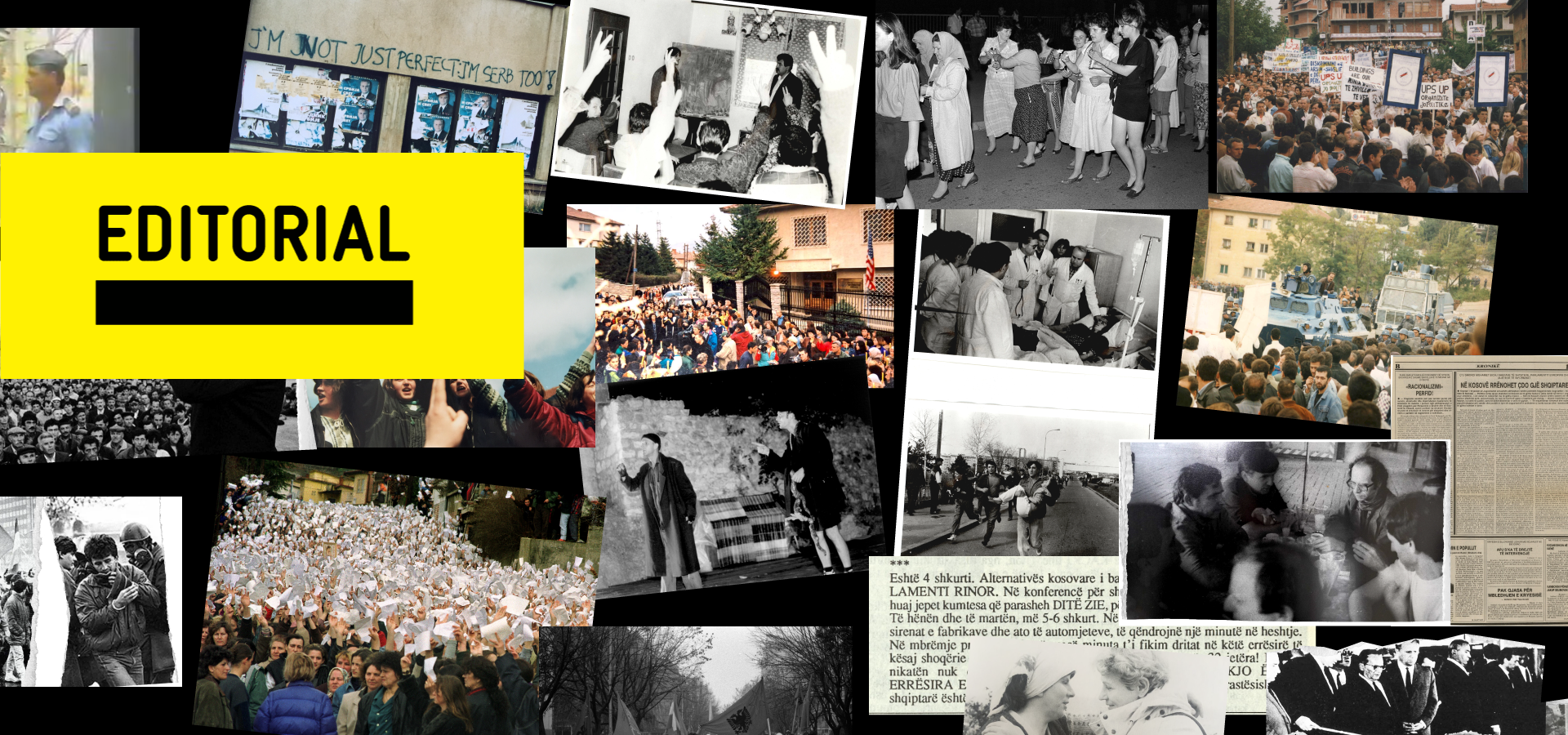

K2.0 returns to the ‘90s

Letter from the editor.

|18.03.2025

|

We wanted to situate Kosovo within the broader history of Yugoslavia and the deep structural inequalities that have long othered Kosovo, economically, politically and culturally.

Yet, it is precisely within such political and structural crises that forms of care, support and solidarity emerge.

These mass firings were more than just economic attacks; they were a deliberate attempt to erase the Albanian presence from public life.

Women played a pivotal role from the kitchen tables to the workshop tables to the negotiating tables.

Because of this, we will certainly return to the ‘90s again.

Besa Luci

Besa Luci is K2.0’s editor-in-chief and co-founder. Besa has a master’s degree in journalism/magazine writing from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism in Columbia, U.S..

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.