When Ibrahim Hoti returned to Kosovo after going on the Hajj in early 1972, he suffered a brief illness and promptly recovered. Little did he know that he had brought smallpox to Yugoslavia, having likely picked it up in Iraq during his group’s return trip. The disease, which hadn’t been seen in Yugoslavia for four decades, soon spread beyond his village, across Kosovo and on to central Serbia and then Belgrade.

Soon after the Prizren-based doctor Durmish Celina (one of the first Albanian doctors in socialist Yugoslavia) identified the disease, the government sprang into action to contain the epidemic. By the time it was declared defeated less than two months later, there had been 175 confirmed cases and 35 deaths; most were in Kosovo.

Public awareness of the epidemic has largely faded in Kosovo. In much of the rest of former Yugoslavia, memory of the events were kept alive by the 1982 cult classic film “Variola vera,” which, inspired by Camus’s “The Plague,” is a cynical take on Yugoslav society that follows the workers and patients in a quarantined Belgrade hospital at the peak of the outbreak.

The Kosovar premiere of Mladen Kovačević’s recent documentary film “Another Spring” at this year’s DokuFest is a chance for Kosovar audiences to reacquaint themselves with the story. Built entirely from archival footage from the period and narrated by Dr. Zoran Radovanović, who was a young doctor in 1972 tasked with running a quarantine facility, the film tracks the progress of the outbreak and the Yugoslav medical community’s attempts to identify and then contain the disease.

With a story-telling approach that is part police procedural, part medical thriller, the audience is kept in tension throughout by the spooky pulsing soundtrack and the ghostly effects of artificially slowed down footage. Periodic news broadcasts from the outbreak are interspersed throughout which give the film an almost anthropological effect and at times a burst of comedy.

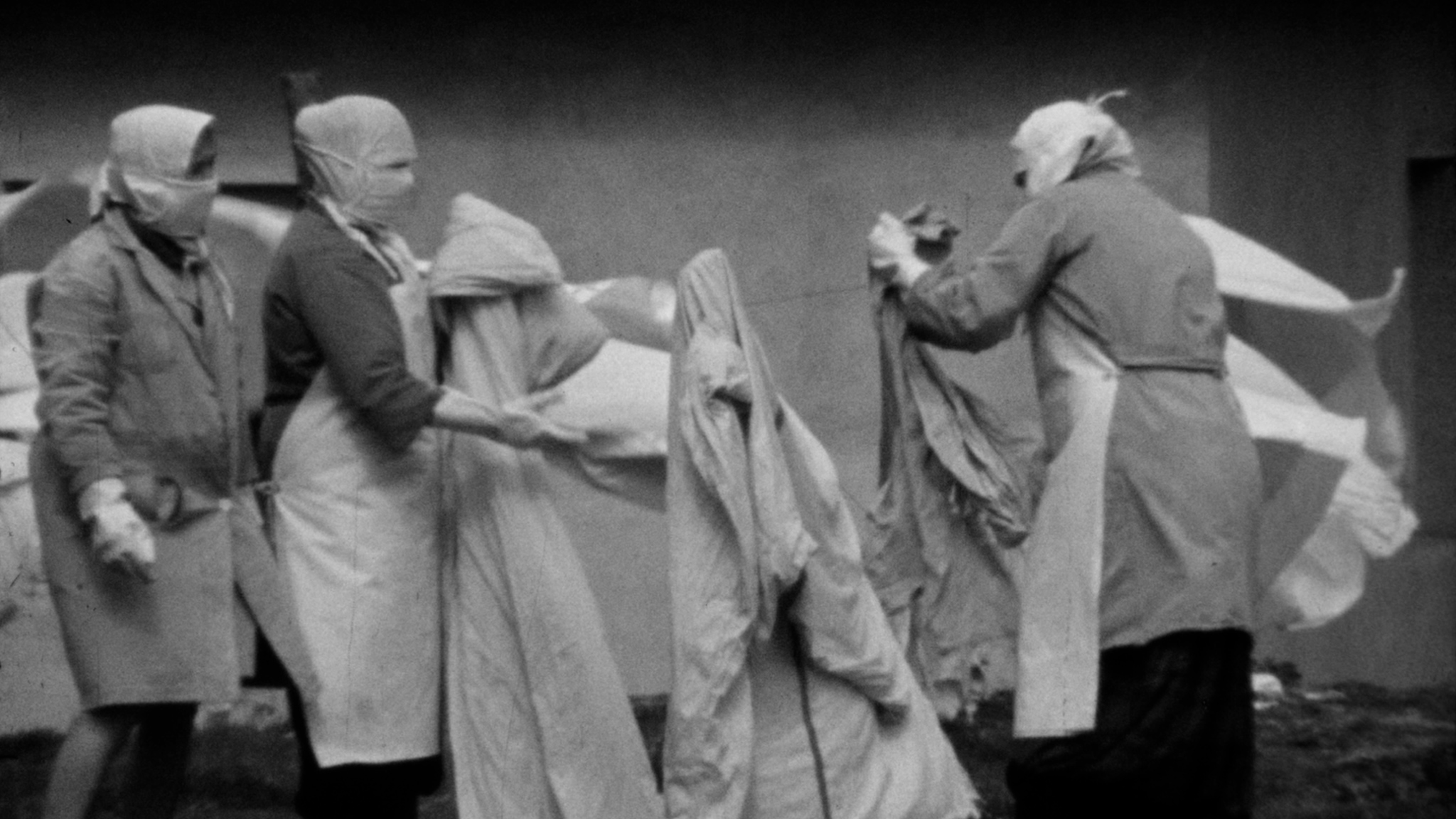

The Yugoslav government implemented strict quarantine rules to contain the smallpox outbreak. Photo: Film still from “Another Spring,” courtesy of Horopter Film Production.

In response to the outbreak, the Yugoslav government quickly drew support from both sides of the Iron Curtain. International medical experts arrived and helped implement mandatory quarantine programs and a nation-wide vaccination campaign that reached almost all 18 million citizens within a few weeks. It’s hard not to contrast the response with the vaccine hesitancy, half-measures and increasing distrust in medical experts that defined the Covid era.

“Another Spring” premiered at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in May 2022 and had its regional premiere at the Sarajevo Film Festival a few months later. Ahead of the Kosovar premiere at DokuFest in Prizren, K2.0 spoke to the film’s director Mladen Kovačević about the inspiration for the documentary, smallpox, and digging through film archives in Belgrade and Prishtina.

For viewers, ‘Another Spring’ will automatically bring to mind the Covid pandemic. How did Covid affect the creation of your film?

If it weren’t for the Covid pandemic, “Another Spring” never would have been made. It’s not just apparent in the inspiration of the film. In early 2020, after the Rotterdam Film Festival where my previous film premiered, I started to plan out the filming of the next one, which was supposed to be filmed in Serbia and a few other countries. But when the pandemic hit, we realized that that type of filming would be too complicated — practically impossible — given the quarantines, travel restrictions and other epidemiological measures that were strictest there at the start.

Because we didn’t know then how long the measures would last, I started to think about what would be a logistically simpler film. Above all, I wanted a film that would be thematically relevant for the moment in which we found ourselves in. Our lives took a sudden turn and everything went upside down, and a lot of themes suddenly seemed banal. That’s how I came up with this idea of making a film on the 1972 Yugoslav smallpox outbreak.

In Serbia, the 1972 smallpox outbreak is remembered as a moment of international solidarity and governmental competence. Did your research into 1972 give you any particular insight into the Covid pandemic?

Naturally, every conversation about this film leads to comparisons with the Covid pandemic, to comparisons between two very different diseases, and two vaccines, which isn’t entirely deserved. For example, in 1972, the smallpox vaccine was already in use for over a century. Although more dangerous, with many more side effects than modern vaccines, it was proven to be effective and it protected against a horrible disease that saw one in five infected people die in agony, while survivors could be crippled for life.

In just a few weeks, the Yugoslav government vaccinated almost the entirety of the population against smallpox. Photo: Film still from “Another Spring,” courtesy of Horopter Film Production.

In that sense, it’s a little tricky to draw direct parallels between the two outbreaks in order to gain some insight into the Covid pandemic. However perhaps we can compare how institutions, the state and the wider society functioned then and now. People no longer trust the state institutions the way they used to. Today, every aspect of life is flooded with government decisions influenced by ratings, profit, corruption, crime, so the average person tends to doubt even scientific facts. Many people equate science with corrupt state apparatuses. And that problem isn’t only ours, local, or Balkan, rather global and civilizational. People lost trust in institutions, in the government, and they seek truth elsewhere.

Of course, the internet proves to be fertile ground for these doubts about institutions and science to just go haywire. This has long-term implications for our civilization, where the atmosphere of unity, solidarity, and competence, like we had in Yugoslavia in 1972, is practically inconceivable.

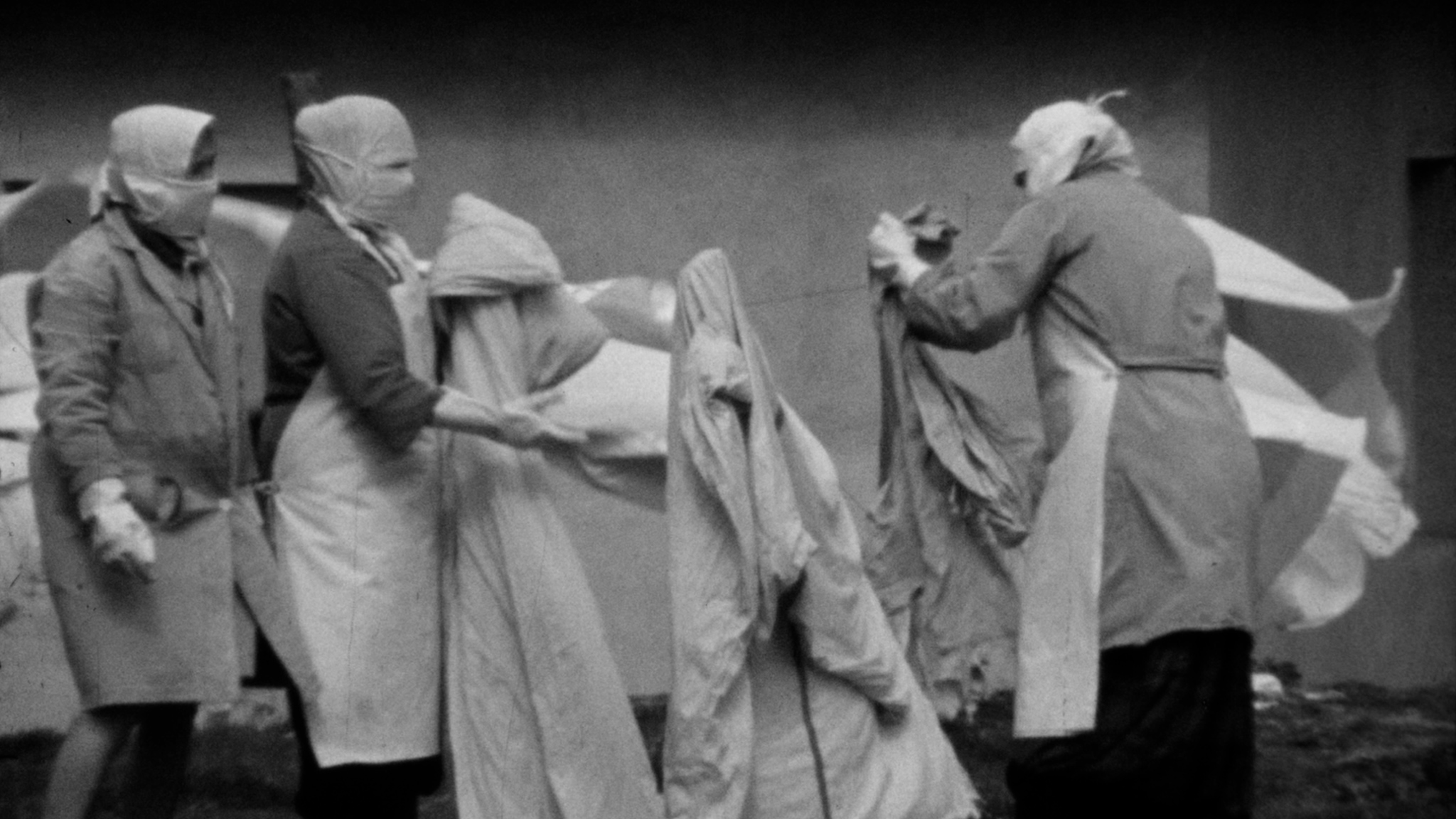

The film is created entirely out of archival film material from the time period. Tell us about what the process of hunting down that footage looked like.

The process of finding archival material can be long and tedious, but in the case of this film it was far simpler than it may seem. The majority of footage we used was taken from a film archive kept by the Radio Television of Serbia (RTS), so RTS became a co-producer of the film by granting us access to their archives. The footage was just lying there on tapes for 50 years and it wasn’t until we decided to use it for our film that it got digitized.

Other sources came from Filmske Novosti, Zastava Film and Radio Television Kosovo. Since the smallpox outbreak was a unique event which was far from the routine filming of current affairs or daily news reporting, everything related to it was registered in TV archive catalogs with great precision. It was harder to find footage from the period that wasn’t about the epidemic because it wasn’t so obvious how to search for such footage besides carefully combing through every single catalog entry pertaining to the period and locations mentioned in our story.

Bit by bit, relying on catalog abstracts as well as with the help of television staff members, we managed to get our hands on everything we needed within a few months. In the end, alongside the epidemic scenes, we ended up using material filmed for travel documentaries, news programs, and other similar things.

‘Another Spring’ is built entirely out of archival film footage from the period of the 1972 outbreak. Photo: Film still from “Another Spring,” courtesy of Horopter Film Production.

All of this was to tell a complex story, one part of which takes the form of a police procedural, prior to smallpox being identified in the story, where protagonists try to uncover what’s happening. The other part is where the protagonists enter the fight against the epidemic, which is more akin to a medical thriller. The material was reinterpreted and adapted so that it fits into this particular film format.

The film is narrated by Zoran Radovanović, who was a young doctor in 1972 and tasked with helping suppress the outbreak. A few years before Covid he published a book about the outbreak. What role did he have in the creation of the film?

Professor Radovanović’s book served as the main source of information for the film. Since he was one of the protagonists in the events of 1972, it was only natural that he would narrate the film. We spent a week in the studio just talking and we built the story of the film through his memories and his intimate reminiscences. The archival material itself was treated with the intent of bringing to mind memories, for it to fit in the rhythm of the doctor’s thoughts. By that I mean the slowing down of the footage which accentuates the menacing ambient sound and which reflects the threat posed by the fast-spreading disease.

Professor Radovanović was very present in the media during the Covid pandemic, he was very critical towards the Serbian government’s decisions. It was really exciting to listen to him as one of our most experienced epidemiologists — one people turn to in order to hear the truth — talk about the smallpox outbreak that happened 50 years earlier, at the beginning of his career. If it weren’t for him, the film wouldn’t have been made.

There are a number of graphic scenes in the film, including footage of people suffering horribly from smallpox with terrible sores all over their body. How did you decide to use this footage?

Ethical dilemmas are always going to be there and these are tough to solve. However, it’s only through explicit scenes and the emotional interplay between narration and the image that a film like this can provide insight into the frightening nature of smallpox. Only in this way does the significance of the 1972 Yugoslav epidemic containment and disease eradication become obvious and indisputable.

When the Covid pandemic began, the Serbian media made frequent mention of the 1972 smallpox outbreak. There was hardly a word about it in the Kosovar media though. Despite the fact that the outbreak started in Kosovo and Kosovo was where the majority of the cases and deaths were, it has almost no role in the public imagination of the country and the younger generation doesn’t know about it. Why do you think that is?

Is the smallpox outbreak the only subject that’s avoided or is it that people rarely discuss Yugoslavia in general? It is hard for me to make assumptions about why these events, which hit Kosovo hardest, would not be spoken about. The smallpox epidemic was identified by Kosovar doctors, while Kosovar healthcare workers bore the brunt of the fight against this terrible disease.

Why do people in Serbia keep discussing this matter even outside the context of the most recent pandemic? Well, one of the probable causes might be Goran Marković’s “Variola Vera,” one of the most significant and best-known films of ours that you can’t forget so easily; this is a work that preserves our collective memory of the event.

Kovačević used archival material from Belgrade and Prishtina to create the documentary. Photo: Film still from “Another Spring,” courtesy of Horopter Film Production.

Another reason is probably the unresolved conflicts in Serbian politics, in which the attitude towards Yugoslavia somehow defines the two sides of the conflict. Some view Yugoslavia as a better society that’s almost unattainable in today’s day and age, while others openly hate it and deem it the root of all that’s wrong in this part of the world. The story of the 1972 smallpox epidemic is the story of Yugoslav society, so it makes sense that perspectives have shifted. Let’s take Goran Marković’s film as an example — it criticizes society as it was back then, given that the Yugoslav society, too, was imperfect. One of the main roles of artists is to question and challenge the societies they live in.

‘Another Spring’ will be a significant contribution to the local, regional and perhaps global remembrance of the 1972 smallpox outbreak. Can you tell me how your narrative perhaps differs from the way the story has been told in Serbia? I’m thinking in particular about occasional framings of the outbreak that cast blame on Ibrahim Hoti (who has been accused, with unclear evidence, of using an alcohol swab to undermine the efficacy of the mandatory smallpox vaccine he received prior to the Hajj in order to avoid side effects) or Muslim Kosovars more broadly.

‘Another Spring’ is a film that tells the official version of events from a reliable narrator’s perspective. It’s neither a polemical film nor a film with a political agenda. The story is too broad to be covered by the film in its entirety, but I hope the takeaway here is as obvious to viewers as was the takeaway I got from my conversation with Professor Radovanović: the official version of events does not place blame on Kosovo in any way. Even Ibrahim Hoti’s individual blame is still unclear, Professor Radovanović says that it’s possible that the vaccine Hoti got just failed.

Even if he’d decided not to get the shot because he feared the side effects or if he’d decided to “wipe it away” — as it was administered through skin scarification — it would be hypocritical to judge him from this point in time, when large numbers of people are opposed to a vaccine that’s substantially milder than the smallpox one. It would be even more hypocritical to interpret all that as Kosovo’s collective issue. Smallpox was absent from Yugoslavia for 40 years, so no one expected it. Even doctors forgot what it looked like.

A global vaccination program helped fully eradicate smallpox only a few years after the 1972 Yugoslav outbreak. Photo: Film still from “Another Spring,” courtesy of Horopter Film Production.

However, the whole thing also had to do with an unfortunate turn of events, coupled with the fact that the 1971 constitutional amendments devolved some healthcare competences to constituent republics and provinces of Yugoslavia. The authorities didn’t get used to this new arrangement in due time, so a tragedy ensued. Eventually, the Kosovar doctor Durmish Celina was the first in Yugoslavia to identify smallpox. At that point, there were patients in Belgrade who were already hospitalized. The Yugoslav society responded in such a way that the epidemic was contained in record time. That’s the most important aspect of this story — Professor Radovanović also puts the greatest emphasis on it.

What’s your next project?

I’m currently in the editing phase with the film “Beginnings: Possibility of Paradise” [“Počeci: Mogućnost raja”] which, through a few stories that take place somewhere that recalls the archetypal representation of heaven on earth, deals with existential tension and ethical dilemmas related to the search for happiness. I’m also preparing for the shooting of “Koryo” [“Korio”], a documentary film essay inspired by a 16-year-old Yugoslav girl’s diary from 1987 — which she wrote when she spent a summer in North Korea with her sister in order to visit their father, who was working there. Through the diary, and the younger sister’s recent return to North Korea, “Koryo” is an intimate journey into childhood and the world’s most isolated country.

This interview took place in Serbian and has been edited for length and clarity.

Feature image: Film still from “Another Spring,” courtesy of Horopter Film Production.