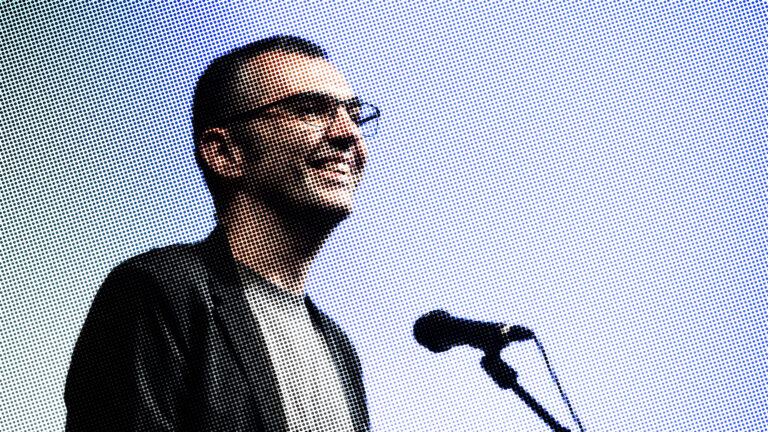

Nikola Ležaić: “Memory Distorts Reality”

K2.0 spoke with the Serbian director about his second feature, a deeply personal tale exploring fatherhood, family memories, and the passage of time.

I had one strict rule: everything in the script had to have really happened.

Still from How Come It’s All Green Out Here?

Davide Abbatescianni

Davide Abbatescianni is a film critic and journalist based in Rome. He works as an International Reporter for Cineuropa and regularly contributes to publications such as Variety, Documentary Magazine, New Scientist, The New Arab, Business Doc Europe, and the Nordisk Film & TV Fond website. He also serves as a funding expert for two European financing bodies.

This story was originally written in Albanian.