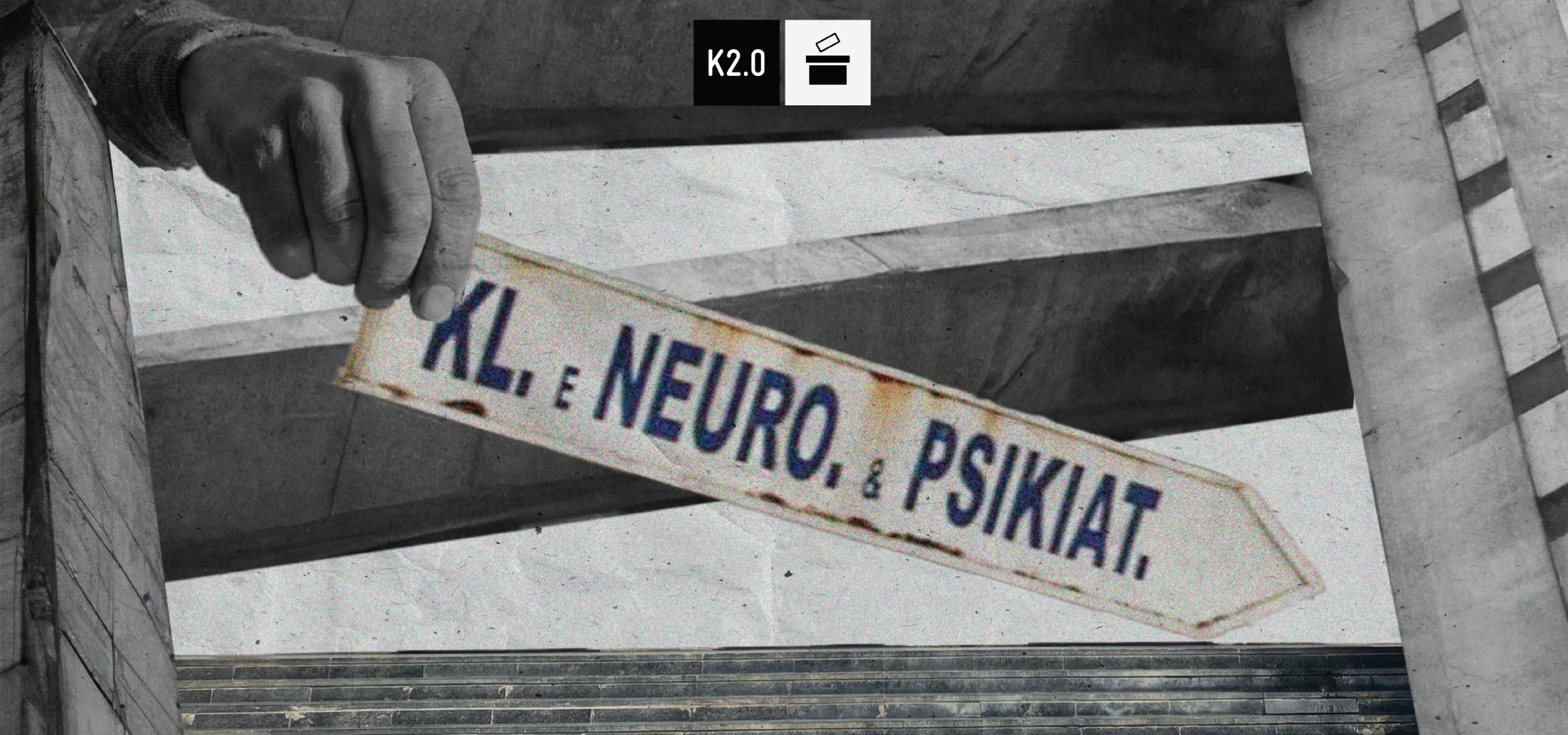

Political parties' pledges on mental health

K2.0 analyzes election programs.

Bind Skeja

Bind Skeja is a political activist and mental health professional. He serves as the executive director of the Center for Information and Social Improvement and is the co-founder of the suicide prevention hotline “Lifeline.” He holds a BSc in Experimental Psychology from the University of York.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in Albanian.