As smokers enjoy their macchiatos on the recently re-opened undercover terrace of Prishtina’s Kafja e vogel, a woman with horns stares straight at them. Placed between two other portraits of women, the mural on the popular cafe’s wall represents key symbols of Fitore Berisha’s artistic expression: women and horns.

When the owner of Kafja e Vogel decided to renovate the pub’s yard, he called his childhood friend Berisha to put her characters on the wall. “The Woman With Horns” resembles one of the paintings in her latest exhibition “Te dalshin brinat” (“May Your Horns Emerge” — an Albanian curse used to scold someone when they’re acting rebelliously), which opened in December at another Prishtina cafe, Hani i 2 Roberteve.

“The Woman With Horns” adorns the wall of Kafija e vogel’s popular terrace.

“The sweetest revolution comes from art, from that bitterness that gets built up inside you,” Berisha stated before her latest exhibition. “And when you think there is no way to come out, it explodes through the paper, pen and colors, and in this case through the horns too.” Through her paintings, Berisha called upon women to let their horns emerge in order to move beyond the inequality.

Growing up surrounded by paintings and artists, Berisha knew from a young age what path she would take later in life. She studied painting during Kosovo’s parallel education system in the 1990s and was in the class taught by Muslim Mulliqi, one of the most acclaimed Kosovar painters.

Berisha says that conversations with the late painter in his house studio during the era of Serbian state oppression encouraged her to pursue her own style. “‘You are on the right path to creating your style,’” she recalls her professor telling her. “‘Your style will define who you are. You need to stay faithful to who you are, to your feelings, to what seems good to you, and then the critique of others around you — of professional people — will come.”

In 2003 Berisha founded Mural Art Group, a nongovernmental organization (NGO) that finalized several projects with the aim of beautifying the city environment through art, and a special emphasis on providing a sense of hope for a brighter future among young people in Kosovo’s post-war era.

Berisha has two homes: Kosovo and Iceland. In 2006 she visited Reykjavik as a tourist and was immediately offered a job working with the City of Reykjavik as a street art theater manager. Later she also worked as a choreographer for an independent theater in Reykjavik. “I didn’t go there as an immigrant, but I became one,” Berisha says.

When the refugee crisis reached Iceland’s shores last year, Berisha would talk to the local media about her experience of being stuck in Kosovo during the war and about how the world, and societies, need to be open towards refugees fleeing their war-torn countries.

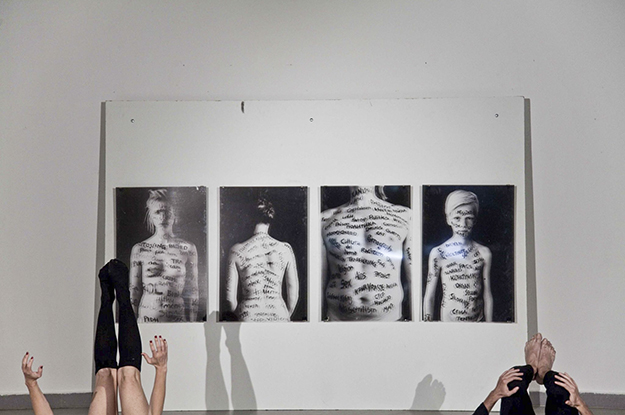

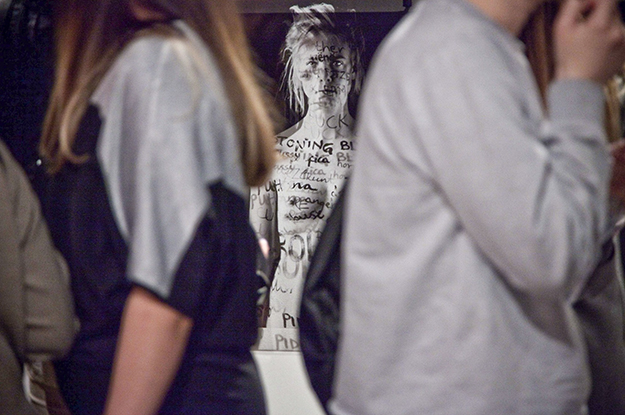

After 10 years, in 2016 Berisha returned to exhibit her work in Prishtina with her project “Revolt Against Violence” in the feminist festival, FemmeArt. Pictures of naked bodies and with messages on them, sent messages of protest against all forms of violence and of respect for fundamental human rights. Her exhibition was accompanied by a dance performance, which through the body movements of Agnes Nokshiqi and Tristan Halilaj transferred the conflict from the more general to the specific within a couple, as a call for women’s empowerment.

Berisha’s first exhibition in Kosovo for 10 years was “Revolt Against Violence,” at 2016’s FemmeArt festival.

K2.0 caught up with Fitore Berisha to discuss her latest exhibition, women’s rights and using art to face her past.

K2.0: “Revolt Against Violence” was exhibited in Prishtina, but also in Reykjavik. How did the experience of exhibiting in both locations compare?

Fitore Berisha: I was very happy to come back and present a project at FemmeArt. I always thought that I needed to present this kind of project in Kosovo, a dance performance, which together with black and white photos, and those dirty words, expressed my revolt, which over the years has built up against conflict. But within that conflict, in the conflicts that are being repeated in the world, there was also a personal conflict. Because the moment you watch the media and see what is happening in another country, you again experience that anger, that conflict [that you have experienced during life]. It’s like the wound becomes partly closed, but when you take off the plaster the wound is still there.

I, as an artist and peaceful human being, would like to see the world putting a stop to conflict. Civilians are the ones who suffer mostly during conflict and that is why I used human faces and wrote those messages, because we all know that there is violence — assaults and massacres — during conflict and we lose something from ourselves psychologically. Every conflict takes something from us.

Berisha’s “Revolt Against Violence” featured images of bodies with protests against violence, accompanied by a choreographed dance performance.

When I talk about conflict I also refer to it as a personal conflict. And that is shown through the performance, where love was the topic. Love which brings emotional blackmail, love which is a struggle. In [the performance in] Prishtina it took a different form — a more aggressive form. Every movement was deeper, more alive.

It was followed by the song “Surrender.” You can interpret the song in different ways but for me it is that men need to embrace the fact that a woman is strong, that a woman needs to have the freedom to decide, a woman needs to be given wings to fly.

We [in Kosovo] show even love with everything that we have. I can personalize it: If I love, I love with all my being. If I put an end to something, I do it because I feel offended, hurt, destroyed. While in [Iceland’s] society everything goes more smoothly. For them it takes longer before they accept their friend or partner. In my experience I needed to earn my friends in Iceland and when you deserve them you will have them for life. Whereas here we have a huge passion and it escalates into huge emotions. And if they’re not reciprocated you will be very emotionally affected because you will take it very personally. You get hurt very quickly and you end things very quickly.

“Surrender” — is it a message to men?

Initially I would say yes, but I would link it also with women. Women need to let go of some things as well. To let go of some patriarchal things that are deeply ingrained. I can say that in our society it is without doubt of great importance for mothers, who provide the first lessons [in a child’s life], to let go of the patriarchy. That culture [learned in a child’s early years] comes from the woman.

A certain amount of patriarchy is being passed down from generation to generation. Regardless of how much we become educated, travel or see other cultures, we are overwhelmed with things like, “I cannot do this or that,” because “my mother or grandma will get hurt.”

It’s also clear that empowerment of women in patriarchal societies is central to your work…

I could never accept the situation of my grandmother, who was an artist [at heart], an artist who didn’t have any education but to whom the art came naturally. She knew how to draw with all materials, to sew and to create beautiful blouses in the village.

It was also the same with my aunt. I never came to terms with the fact that a woman who was so dear and lovely didn’t get anything back. I will never forget her saying, “I beg you not to allow your life to become waisted like mine has been.”

Much of Berisha’s work is inspired by protesting against patriarchal societies, in which women are not able to fulfill their true potential.

When I went to Iceland I was in need of some self-reflection and went to consult a psychiatrist. He would say, “you decide what you want to share.” I said, “I’ve made a plan to share things in chapters, because it is for my good and benefit to open up those shelves, but where I am from is important. Because today I am who I am because of that country [Kosovo].” But I’m still very mad at the patriarchy of that country. I am mad at women who are my friends, cousins and colleagues, who are still deferential and they don’t need to be.

Did knowing that your grandmother wasn’t able to fulfill her potential in arts add to your motivation to pursue that path yourself?

Yes, very much so. But this is also connected to the thing that from a small society I moved to a small society. Kosovo is like an island because we don’t have freedom of movement. I went to a society [in Iceland] that enjoys all the rights and it was like a cultural shock to me. Me, as a mother, as a single mother, went to a place full of single mothers enjoying life and taking to the streets in the city to protect their rights.

And then my therapist told me to do art therapy and to bring out all of the things that were weighing me down.

This idea of art therapy — can you say something more about it.

Many people speak through art more than through words. There are people who don’t know how to express themselves but through art they can see where they stand, understand their traumas, their post-traumatic stress, how happy they are. Art therapy is a healing process.

[As an art teacher in Iceland] I used to work with children with autism. Through art-therapies I tried to give them the freedom to express themselves because they are sensitive towards noise, words and pressure to be like others.

During the process of working with autistic children I could see that I was also helping myself. I would use the same technique with myself during the long dark nights in Iceland. I would draw every day after work. I would switch off the phone, the television, just play music and draw. I wouldn’t know what was going to come out. Now when I look at that work I call it unconscious art. From unconscious art many nice things can come out. It is nice meditation and every time I feel worried or irritated I just sit down and get lost in my world.