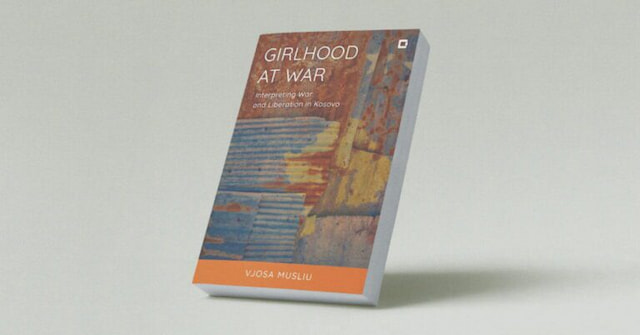

From Calabria, with love

How a small part of my ancestry shaped my connection to Kosovo.

In-depth

More

Between colorful claws and DJ sets

MATALE discusses her artistic journey from Tingle Tangle to Serpent Claws.

Perspectives

More

Longform

More

When the absence of care becomes deadly

How the lack of healthcare in Kosovo fuels suicide and the mental-health crises among transgender people

Videos

More

Recommended

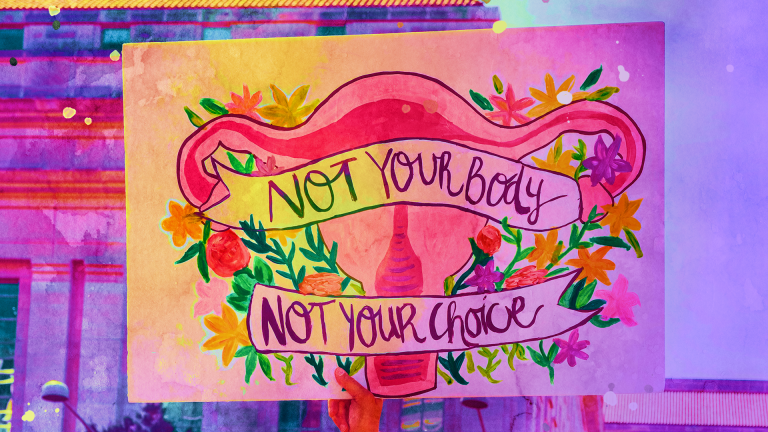

‘Today we march, every day we fight’

In photos: the March 8 call for gender justice.

Podcasts

More

Trending

Frikë nga kritika

Në këtë kuptim, kritika nuk është kundërshtare e artit, por një nga mekanizmat që e mban artin të gjallë. Ajo ndihmon në dokumentimin e lëvizjeve artistike, në vendosjen e artistëve në një kontekst historik dhe në sfidimin e ideve apo tendencave që dominojnë momentin. Përmes kritikës, publiku mëson të mendojë...

Best Bits

Subscribe to Best Bits and receive our best content of the week.

Donate

Help us bring you the journalism you count on. All amounts are appreciated

Photostories

Explore more