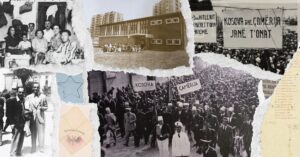

From Calabria, with love

How a small part of my ancestry shaped my connection to Kosovo.

In-depth

More

Perspectives

More

Longform

More

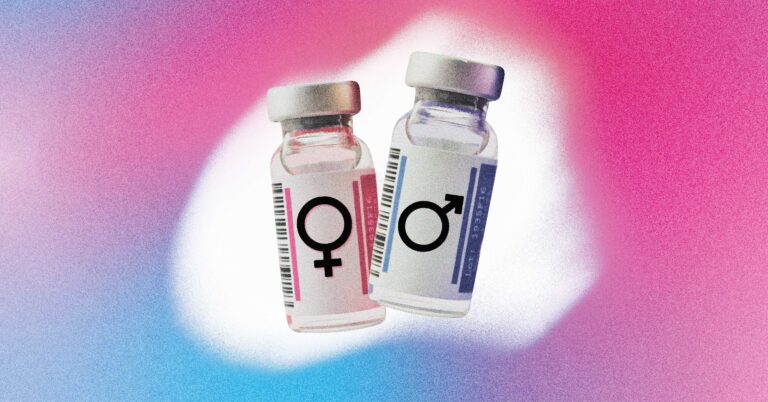

When the absence of care becomes deadly

How the lack of healthcare in Kosovo fuels suicide and the mental-health crises among transgender people

Videos

More

Recommended

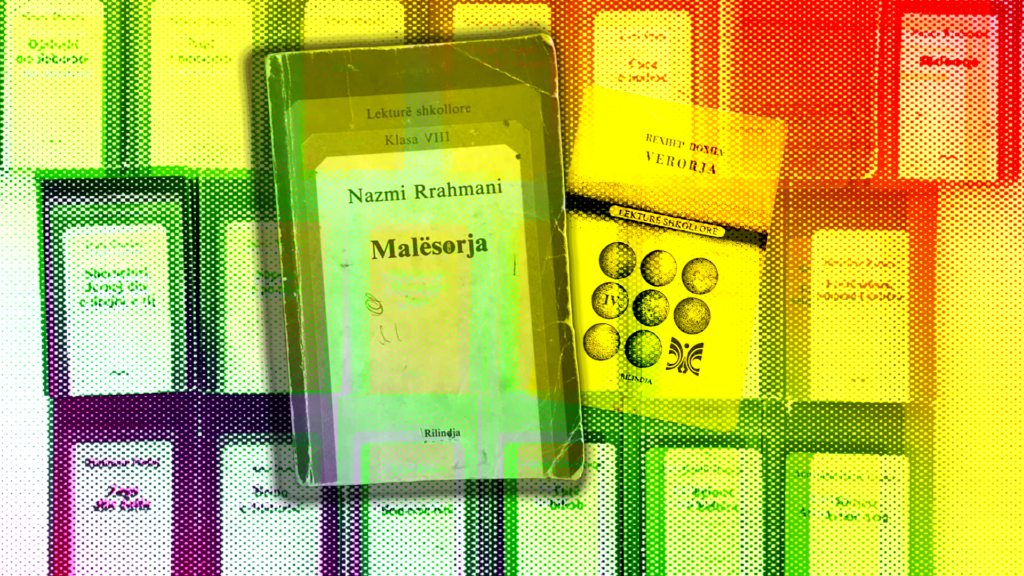

The “unaltered” literature of Kosovar schools

Literature in schools reproduces derogatory and racist language without critical examination.

Podcasts

More

Trending

Anatomia e dhunës në shkolla

Siguria kërkon strukturë të qartë përgjegjësie. Bashkëpunimi mes shkollave, shërbimeve sociale, policisë, prindërve dhe akterëve të tjerë duhet të institucionalizohet dhe të funksionojë mbi baza të qarta përgjegjësie dhe llogaridhënieje. Korniza ligjore ekzistuese është relativisht e plotë; sfida qëndron te zbatimi i saj i qëndrueshëm dhe te mungesa e mekanizmave...

Best Bits

Subscribe to Best Bits and receive our best content of the week.

Donate

Help us bring you the journalism you count on. All amounts are appreciated

Photostories

Explore more