Perspectives | Politics

Disciplining the diaspora

Elections, political legitimacy and Kosovo’s diaspora vote.

14.01.2026

In-depth

More

The elections are over, it's time to move on

VV now has the opportunity to translate its electoral mandate into institutional stability.

Perspectives

More

How can Kosovo’s opposition parties compete again?

An opposition refusing to accept realities that VV understands all too well.

Longform

More

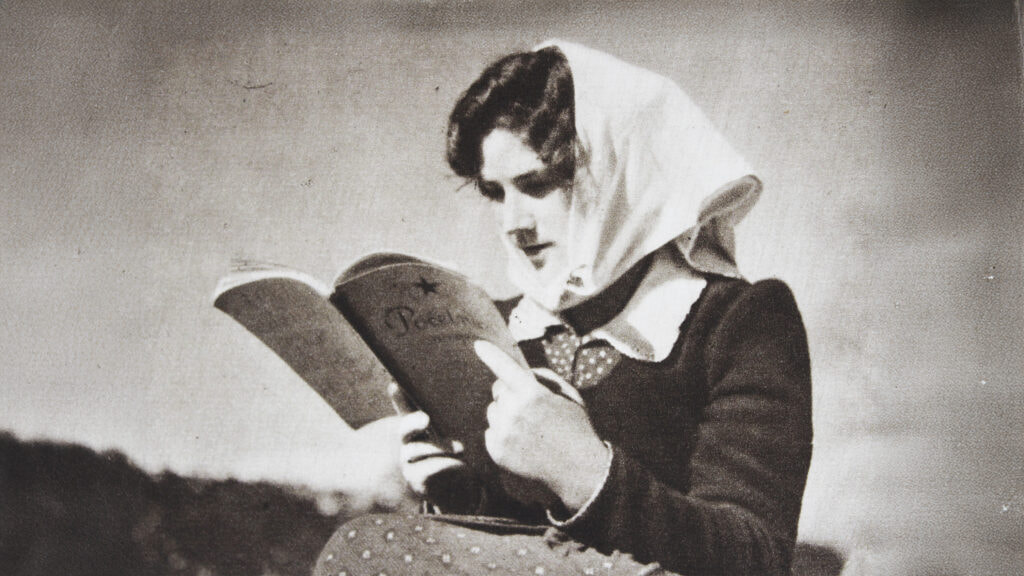

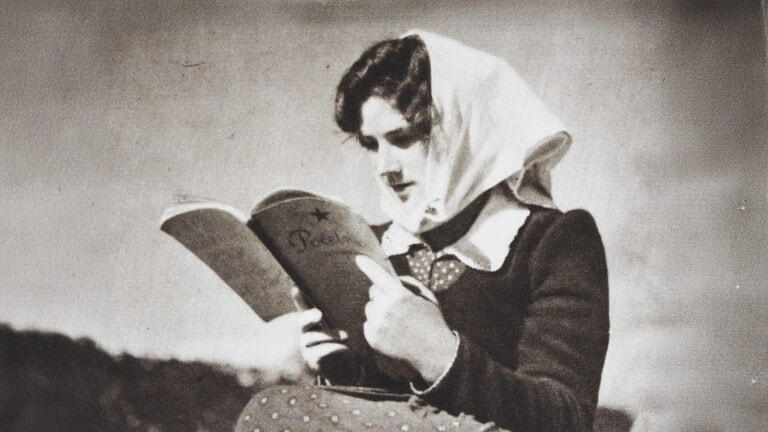

Women’s Anti-Fascist Front in Kosovo

Between emancipation and propaganda, and under conditions of survival

Videos

More

Recommended

Women’s Anti-Fascist Front in Kosovo

Between emancipation and propaganda, and under conditions of survival

Photostories

Explore more