In the context of an exhibition about collective memory, we could just as well re-publish Vincent WJ van Gerven Oei’s review of last year’s Onufri Prize, “And Find a Rope Hanging There,” that appeared in Exit. Like last year, the main promotional image of this year’s Onufri Prize exhibition is not part of the exhibition, the heating at the National Gallery still doesn’t work (doesn’t exist?), and the connections between many works are tenuous indeed.

So, history repeats itself. The Onufri Prize started in 1993 as a national competition for Albanian artists and in 1998 morphed into a curated international exhibition, with a curator being appointed after an open call.

No more than four of the twenty curated exhibitions since have been curated by women; and never in the history of the National Gallery has a woman been its director. The rumor in Tirana is that the person slated to become its eighteenth director also just happens to be a man. Memory should challenge us to a better future, not keep us stuck in past regressions.

So, history repeats itself. This year, the winning curator, Gaetano Centrone, titled the show “Au Fil Du Temps – Collective Memory, Personal Memory.” Like last year’s exhibition, “Stranger Than Kindness,” the curator’s appointed title uses foreign phrasing to stand in for concept. We are not fooled though.

What Centrone does achieve is the selection of a few good works. Of note are Montenegrin Jelena Tomasevic’s short stories swirling around childhoods in the former Yugoslavia, published alongside dollhouse-like objects of a slightly Freudian nature (a bent sofa, the endless loop of a running track, a sprouting pile of dirt under a small lamp). The narratives highlight tricks of memory and observation, marrying the personal with the geopolitical — in this case, the effects of ethnic cleansing and genocide on everyday people.

Calixto Ramirez’s installation was one of the standout works, inspired by the city it was exhibited in, Tirana. Photo courtesy of Maja Lako.

While Tomasevic’s work stems from a deep personal connection to landscape, Mexico-born, Rome-based artist Calixto Ramirez made an installation in reaction to his recent visit to Tirana, presumably his first: broken stacks of ubiquitous red brick are crowned with full raki glasses, a beer mug, and other assorted drinking vessels, which stand alongside a black-and-white video of the city’s central pyramid. It is not clear which is more fragile, the bricks, the communist-era raki glasses, or the crumbling pyramid crawling with bodies.

Albania-born, Berlin-based Vangjush Vellahu’s research on “unrecognized states” struggling for sovereignty, Fragments I (5+1) (2016–2018), unfolds through a three-channel video installation of testimonies — personal stories and anecdotes from residents of six such places. The voice-overs layered on top of moving landscapes (the latter strikingly similar for distant geographies) don’t seek to make a case for these states but rather act as oral histories.

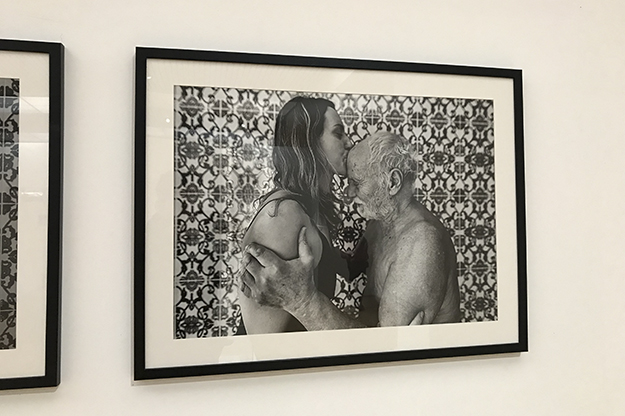

In Kosovo-born, London-based Alketa Xhafa Mripa’s video work the viewer enters a deeply intimate space as the artist bathes her father — himself a well-known artist in the region — him in profile and her with her back to the camera. Barely exchanging any words, there is still transfer.

The tenderness of Alketa Xhafa Mripa’s work featuring her father stood out, though its display could have added further impact. Photo courtesy of Maja Lako.

The show leans on its strong works, and it unravels in the places where the curator’s hand feels most present. Some works seemed to have been included to simply fill space: video stills of Vellahu’s take up a full gallery, the unnecessary hanging of Xhafa Mripa’s photographs weaken the impact of the video, and a trite wall painting by the Italian-American duo Emiliano Perino and Luca Vele seemingly makes a commentary on Albania’s drug economy, but reduces complexity to a buoyant infographic, but one missing the info.

All of this is not helped by the wasted language of the curator’s wall text, which makes unclear whether ideas were lost in translation or were just never there at all. The text proves that the curatorial concept does not hold and relies too heavily on the fact that engaging concepts of both personal and collective memory is already one of the most common tropes of young Albanian artists working today. Why is that? We get no new insight from this show.

So, history repeats itself. Leonard Qylafi, also part of last year’s Onufri Prize exhibition, is here again with his Gerhard Richter-like blurred paintings. And “someone called” Fani Zguro (as van Gerven Oei referred to him), the curator of last year’s exhibition, this year is featured as one of the Centrone’s ten selected artists.

The most uncanny moment, though, happens before you even enter the exhibition: Guri Bulovari, an outsider artist from Pogradec who showed in Tirana for the first time at last year’s Onufri exhibition and was the show’s hit, has a solo exhibition that one passes on the way to Onufri. A cold room, a misleading image, and last year’s winners. See you next year.

The Onufri Prize exhibition, “Au Fil Du Temps – Collective memory, personal memories” is on view at the National Gallery of Albania from 20 December 2017 to 30 January 2018 and features the work of Zeni Ballazhi, Adi Haxhiaj, Koja, Perino & Vele, Leonard Qylafi, Calixto Ramirez, Jelena Tomasevic, Vangjush Vellahu, Alketa Xhafa Mripa, and Fani Zguro.

Feature image courtesy of Maja Lako.