Driton Selmani speaks in metaphors and allegories, even when you run into him on the street, where he still displays his humor and underlying thoughts if you push him a little.

His Instagram account has become a fun, insightful journal through which we see what he sees in small things, like a random white van or a broken bench. This is important, because in Selmani’s work the small things, and the subtle myths that go by unnoticed come afloat to a place where it’s hard to ignore them.

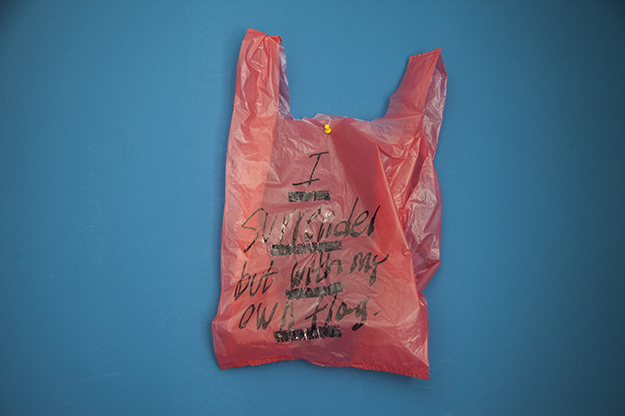

Playful and subtle, in one of his ongoing works Selmani has chosen plastic bags as his artwork surface, recontextualizing them with new meanings through drawings or messages written on them. Kneeling down in a corner of his studio he reaches over to a pile of colorful transparent plastic bags — just like the ones you get in any small kiosk, not of the quality of the big supermarket chains.

Some of them he shows off include what he refers to as his wife’s “love letters” — shopping lists, including tomatoes and cucumbers, resituated onto the surface of the plastic bag he used to bring those goods home. He finally reaches out to his favorite plastic bag, which reads: “I surrender, but with my own flag.”

Selmani is currently developing an ongoing series of work revolving around plastic bags. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

It is precisely a flag which put him in the public conscience earlier this year. Just three weeks before the tenth anniversary of Kosovo’s independence, he took down the large Albanian flag presiding at the roundabout at the entrance of Prishtina and replaced it with a giant ‘offside’ flag. The pattern of red and orange rhomboids that the referee’s assistant usually shows in a football match to indicate that a player is in an illegal position flew over Prishtina for a few hours until it was taken down by municipal authorities.

The artwork provoked both threats and disparaging comments, but also strong popular support from citizens and even politicians, including the mayor of Prishtina himself. Selmani’s ‘offside’ flag came at a time of strong political antipathy, and of little public enthusiasm towards Kosovo’s tenth anniversary of Independence.

His interest in larger public interventions is slowly growing. Last year, he created a gigantic talisman to protect against the Evil Eye, which had the honor of being housed in the port of Amsterdam, protecting the Dutch capital from bad spirits during the Amsterdam Light Festival.

In 2016, in Polignano a Mare (Italy), as part of his piece “Wanderlust,” Selmani put a giant orange life jacket on the enormous statue of the Italian singer Domenico Modugno (known for the famous chorus “Volare, cantare…”), turning him into an arriving migrant who leaves the sea behind with his arms aloft, as if he had survived the most terrible of journeys.

This month, Selmani was back at the National Gallery of Kosovo with the collective exhibition “Fog”, curated by Avi Lubin, where he appeared alongside four other artists: Albert Allgeier, Fatmir Mustafa-Karllo, Gazmend Ejupi, and Luan Bajraktari.

K2.0 met with Selmani at his studio in Prishtina to speak about offsides, myths, the fog in which the wolves attack, and reality as a consensus.

K2.0: Do you have an easy time explaining what offside is?

Driton Selmani: There are a lot of offsides. There is an offside in sport, there is an offside in real life, and there is an offside which also represents societies and situations, or situations of societies, or positions of societies, because every society has or is in one position.

When you put the offside flag on the roundabout in Prishtina, the message is straightforward. Are citizens, like in football, complaining to the assistant referee for raising the flag, or applauding him or her? Or, as happens in any match, do we have both? What is their role in your offside?

I think the role of the citizens was like in football. They say that when the players play at home we have an extra player. I think I had an extra player with me ‘cause I was discussing my idea with some close friends, and that really pushed me to do it.

I was just the guy who waved the flag, or who put the flag there. I think after I did it I understood I was one of the voices which many wanted to raise, and wanted to do what I did. The artwork was bigger than me, my ego and everything around.

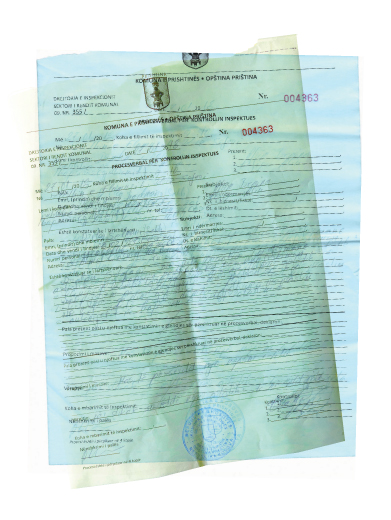

As part of Selmani’s “Red Tape,” the large Albanian flag at the entrance of Prishtina was replaced by a large ‘offside’ flag in a difficult public intervention. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Many described this work as hitting the nail on the head. Even the mayor of Prishtina, Shpend Ahmeti, liked the intervention, at least based on his words… Nevertheless the municipality still gave you a fine.

It depends what kind of artist you are or where you live, but I think the role of the artist in the region where I hang around is not just to be an artist, but also to try to touch a nerve. In this case, I think I was looking for the central nerve of the society in order to… not to provoke, but to doubt the whole reality — sometimes we just end up there, we just lay in the wrong reality.

But going back to the mayor, I think he just liked the idea. But honestly I was never in touch with any of the authorities, not with the left, nor with right side of politics because I am too dumb. But I belong to a one-man army and one-man party which is me and myself.

There are artists who ask for permission to make an intervention in the public space, and you did not. Do you think asking for permission delegitimizes the work itself?

There are conformist and nonconformist artists. I think I belong to the second group. I never negotiate my ideas with the norms because they put you on different pillows, where you can either have good sleep and a bad sleep. I think I was sleeping on a bad pillow and that’s why I did it. If I had a soft, goose [feather] pillow I would never do this.

Because of “Red Tape,” the municipality gave two fines to Selmani and the company that replaced the flag, adding up to 700 euros. Photo courtesy of the artist.

What happened with the fine?

The inspection department, which belongs to the municipality of Prishtina, gave me two fines. One was for myself, as the artist who did “public space damages.” The other one was for the company that I hired [to change the flag]. They removed the big fine of 500 euros [for the company], but I still had to pay my fine, which was 200 euros. I had to because they told me if I don’t pay it I cannot leave the country. I cannot leave the stadium… (laughs). I had to pay because I scored an own goal.

What do you think about the fact that you had to pay the fine?

I bit someone. I did not just bark, I bit someone. So I knew that someone will come and bite me back, I was prepared. But I am very bad at maths and finances and I didn’t think about how much it would be. I only knew, because of the Constitution, that I wouldn’t go to jail, because I didn’t damage or commit blasphemy towards any symbol of my country.

How do you see the removal of the bigger fine? Is it something like a pardon?

After I did it the police took me and they were very rough because they thought I am an activist from the left, or from the right — I don’t know, I never got these political waves. After we talked, they also understood that this was an artwork — what a way to introduce my profession to the policemen!

[After that,] everyone was being nice to me, everyone from the inspection, from the police, and unofficially everyone supported my action — in the police department, on the streets. Wherever I went everyone just said what you did was very good. But I also received some threats on social media.

What do flags have that mean they raise these very opposite feelings?

It depends what flags. They [all] have symbols, semiotics, colours. And the rest is just… I think it’s garbage. Because they just represent the wrong feelings in people. Flags are used as a trampoline to somehow boil black water, and given as food to people so they can somehow become brainwashed. I think a flag is a trick of the magicians really.

I also think it represents the very wrong pride of people, in terms of nationalist feelings.

Is there a wrong and a right pride? What is the right pride?

The right pride? If you never show any symbol, if you never show any division. “My red is redder than yours; my blue is bluer than yours.” Red is red and blue is blue. A pole is a pole.

In the current collective exhibition “Fog” at the National Gallery, you had a work in which some red boxing gloves were completely stuck inside a mess of barbed wire. Was the red any allusion to the red of the Albanian flag or the Albanian identity?

No, the only reason the gloves are red is because they are red in professional boxing, so these are the ones you find in the shop. [The work] is an allegory of ‘Raw and the Cooked’ an essay by Claude Lévi-Strauss.

His book deals with myths, and I am also dealing with a lot of myths around me, so the work tends to bring on view the idea of what food we are served — reality’s food, the reality I go through everyday.

Sometimes it’s very liberal, sometimes it’s very radical, but I never understood which one is which, so it’s a combination of both. The raw and the cooked. Some people people eat their food raw, some cook it.

Here in your studio we see this framed plastic bag with the words “Reality is a consensus” on it. Does that work connect to this consensus? Are there situations in which you must accept unpleasant realities and establish a consensus?

I think choosing raw and cooked meals is very often not even a choice. We know people who live in areas where they can only have raw food, and we also know that two thirds of the food served in very developed economies around the world goes in the garbage. It’s not an idea of what you can choose but what is being served to you.

I don’t know if it’s linked to the other artwork but to me reality is a consensus because I live with a lot of ‘me’s in myself, with a lot of Dritons, which don’t really accept reality. I also live with a lot of dark matter and mythologies. We have to make a consensus.

We were talking a bit about symbols, like flags. I’d like to speak about a symbol you used for the “Eye to Eye” installation, that was part of the Amsterdam Light Festival in 2017. It was a huge talisman to protect against the Evil Eye, and it stood in the port of the city. This is a symbol that goes back to Mesopotamian times, and is relevant to different religions, from Buddhism to Islam and Christianity, displayed in this case in a very multicultural city. Is it a work that could also be displayed and protect any city in Kosovo?

Maybe it can work. I never thought about the idea of how the eye can stand in Amsterdam or here or wherever. As you said, Amsterdam is very multicultural, so I just thought about how I could give something that is a spiritual protection to that city?

The only gift I could think of is the [protection against the] Evil Eye. I wanted Amsterdam to be safe. I think the eye, when people saw it, it really gave you a feeling of something. Maybe people didn’t know exactly what, but it gazes at you. It communicates with people. It was a large-scale artwork and it was a good spot.

In Kosovo, in the context of here, sure, why not? Maybe we also need [that protection], but we need more than one!

The symbol is also connected to Islam too, as part of the Hand of Fatima. Did you consider this link in any way?

I never thought about linking it to any religion because for me symbols represent things beyond religion, and the Evil Eye doesn’t belong to any specific culture. It’s widespread from one corner to another corner of the world. It was found simultaneously in different places.

I was searching for industrial designs from the past, and how can I remake them and put them in the context of now. For me the Evil Eye is a pop icon, before [Andy] Warhol or anyone put a mirror on pop icons. So I said, okay, let’s find an icon from the ancient times. There were other symbols, but the Evil Eye was a protection gadget for the city, which needs spiritual protection.

This is a work that transmits spiritual protection, but a lot of your works are related to this idea of keeping the status quo, while also keeping dangerous or risky elements that should not be there. They’re together in a sustained suspension, a risky balance. So, connecting to an old work of yours, can two watermelons really be held in one hand?

I found myself in situations where I tried to use tools, or to produce artworks which describe things that people just say, and illustrate the literal. I try to get the literal out of that context and see how it would actually look. Maybe holding two watermelons in one hand, like a friend of mine told me, is an image that I have to remind myself everyday of my life.

“You can’t hold two watermelons in one hand” is an Albanian saying that Selmani brought to life in his work. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Because it can work or because it cannot?

Because I think I’m quite often in that situation. But actually it can work! It could be for like a millisecond. I tried it, it worked! And I did break two watermelons. Maybe sometimes trying something for just one second gives you an explanation of how things look from the other side.

Reading more about this work we learn that the two watermelons are connected to Kosovo’s recent history, and its status in between times, in between periods, in between regimes, moving towards this promised future. There is also an Albanian saying that you can’t hold two watermelons in one hand… You may be able to hold two watermelons on the top of each other for that millisecond, but can this reality hold for long?

No, no, no. That can’t hold for long. But also because it is not natural to hold two spherical objects on the top of each other. The rule of gravity doesn’t allow you because of the weight. But sometimes I’m stupid enough. I talk to my father, and he just laughs at me. Declaring a war with gravity is not one that you will win, because gravity is something you cannot change.

But trying to reach the bottom of it and trying to decode it can give you knowledge about other things. I think sometimes trying to hold two watermelons in one hand, trying to put the talisman to protect against the Evil Eye somewhere, trying to make a ten-meter offside flag does something. It doesn’t do the whole thing, but it does something.

Maybe that is the mission of artists. The mission of artists is not to change the whole world, but to try to burn some old flags, to remove some flags, to score own goals, you know? In order to wake up somehow from the daydreaming, and to shake things.

There is a work of yours, “Call it fate, call it karma,” with two legs becoming one and going into one single shoe that does not fit the right foot, nor the left foot. Writing about it, Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei compares this to Oedipus Rex, whose central character’s feet were pierced and bound together as an infant to prevent him from crawling around. He calls it a “post-ideological centrist shoe,” and a “risky balancing”. So, “not taking sides,” is that a big risk?

It’s a huge risk!

I think Vincent was very good at reading the artwork and trying to put it in the context of when and where it was exhibited. The first time the artwork was exhibited in Tirana (at Tulla Culture Center, in 2015), so sometimes [works are] also exhibited with the culture around.

The idea of this work is an extraction of a saying in Albanian: “he or she has put his two feet in one shoe,” meaning that he or she now is walking in a controlled way. The control is exerted by someone else, of course, and that someone else can be your wife, your friend, your parent, your partner, your prime minister, your boss…

I wanted to freeze that moment, and call it fate or karma. Because it can be both, if this happens. Maybe because you didn’t stand up to someone or something, or maybe because you misused your two feet, or you did not acknowledge your walking style or your path.

Selmani’s “Call it fate, call it karma” required creating a shoe that does not fit neither right or left foot, which he did in a shoe factory in Suhareka. Photo courtesy of the artist

In Kosovo today it keeps being hard sometimes to even understand who is what within the labels, ideologically.

This is my case study as well, and “Raw and the Cooked” talks about this, because for me now, I don’t know which one is left, and which one is right, who is punching me and who is putting some itchy barbed wire in my skin. This is a combination of that, and the whole installation also functions as a tumbleweed, so that’s something connected to that.

I feel it’s the same for other artists. We often see works that do not put the artist in a position of left or right, they have a “neutral” meaning, they don’t take sides either.

But you have very, very, very good left artists, or left activist-artists, or left artist-collectives, or people who do actions but don’t call themselves artists. You also have interesting right-wing artists. I don’t know about this because I never try to belong to any ideology.

But is that possible? Not to belong to any ideology?

I think it’s very possible, because why belong to any ideology? You can be your own ideology, as I said earlier, I have a lot of things in my mind that fight with each other so I belong to my ideology, and to the things that are close to me, or which somehow try to cover me. I belong to the stories around me.

“My country on my back”, with its knives hanging from fragile helium balloons, is again about two elements that should not be together maintaining a risky balance. There is a constant element of danger and risk present among very opposite figures, but they live together. This suspense, is again an allegory of the political, the social, that is not changing. The work of the flag challenged this status quo by making it obvious. Do you think of challenging further this suspension? Breaking the suspension?

I think “My country on my back” is a sort of poetry. I’m very bad at writing poetry but I try to make physical objects that are poetry. For me this one is like a dance, because the knives, the suspension and the wire, they have a tension and they move around.

In “My country on my back” Selmani hung handmade knives from helium balloons. Photo courtesy of the artist.

You also see a knife and you forget that there is another knife right behind you. It all started like this, and the symbols are not repetitive but I choose them because of the meanings they have. Sometimes I choose “Raw and the Cooked,” other times I use helium and a handmade knife (and bear in mind helium doesn’t stay for long and it goes away….).

You also had another work, “Wanderlust,” in Italy, in which you put a giant life jacket on a sculpture of Domenico Modugno…

I was invited to have a solo show in Polignano a Mare in Italy. I learned that there was a boat found nearby with more than 200 migrants who were already dead in the boat when they were found. They died of dehydration at sea. All the dead bodies had life jackets. They didn’t die because they couldn’t swim but because of the days spent at the sea.

The town had this large statue of Domenico Modugno, who sings the famous “Volare, cantare” song. They have a huge statue of him [with open arms and the sea behind him], and to me this represented something else at that moment. I produced this huge life jacket with some friends and put it on the statue. It makes sense because he looks like he just came from the sea saying “I survived, I am an emigrant.”

[Modugno] also had this crazy urge to travel, and wanderlust means the desire to travel. I wanted to convey to Italians the question: How would you feel if an Italian is an emigrant and comes here, and not just a random one but a very popular one like Domenico Modugno?

I had a fight while I was putting the vest on the statue with a tourist because he said I ruined their picture opportunity, but the local Italians there loved what I did and asked me not to remove it. The police came after a while and took it off but everyone liked it and it ended up being reviewed in Flash Art magazine, which was a very good thing for me.

Driton Selmani’s “Wanderlust” is a call to rethink the concept of the migrant. Photo courtesy of the artist.

I think it gave a message. I look for small, meaningful actions, I look for nerves in society that I can touch and then people can understand why this is like this or why Modugno has a giant life jacket now.

I never try to use the misfortune of someone and reproduce an artwork that represents me. I like to put the misfortune on the big screen, but not with my name. I don’t want to buy 10,000 life jackets like Ai Weiwei and do a very sellable artwork. No, I hate that.

A lot of your works have been exhibited more abroad, than here. Why is that? Is it because Kosovo doesn’t offer this platform or…?

That’s a question I cannot answer. That’s a question for the people who work in exhibition making in Kosovo. For me, I don’t understand it, I never understood this. But still there are a lot of trampolines.

If you lack opportunities here, you look for opportunities somewhere else. If this trampoline is used by another kid, you find another trampoline. If this basketball is being used by those muscly, half-naked players doing dunks, you leave. Or you go and produce your own basketball court.

Maybe it’s related to the language I use in the art making, what kind of artist I am. I don’t remember the last time I exhibited in Kosovo.

Thinking of generations of contemporary artists, you were born in 1987 and are a bit younger than what is considered the first generation of contemporary artists. Do you feel different from that generation, and what do you think differentiates you from that generation of artists?

I’m quite different because of a lot of elements. First of all I was not raised in an urban area, I grew up in a village in Kaçanik. This, as well as the time I was growing up in had an influence. When I was introduced to the art world these artists were already established. I observed them and tried to bring my own background and put it into the art making.

They also started from no internet, and I came with internet. Internet artists and no-internet artists have a very different approach, and also other elements which I think make me and the second wave different.

Most of the artists from the first wave were also hanging out together, and they had a similar language as well. Me? Maybe I am also not so different either…

Considering your often humorous and innocent-like perspective, has having a family now changed your approach to art?

It has changed everything. Now the reason I do small scale or large scale artworks is because of the situation I am in with my family. I am so much needed, and I cannot just make my flat a whole studio and just paint, because I need to be cautious with the kids.

Having kids is like having a gallerist. They put you under pressure to produce or to be more productive. And you learn, because they start to walk, and talk and they start to ask questions. My first audience is the kids, and we make bread together but a bit of that bread is also going into art making.

Driton Selmani tries to use his personal experiences to create his artworks. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

Your work perhaps has a fluid connection with emotions and we’re not used to men showing emotions as much. Do you find it easy in your surroundings to speak about your personal emotions?

I don’t draw my tears or tell stories of how I cry, but I try to get the feeling out of the tears and add some element and represent it. I think it does something to the society because a sincere story is always a good story. It only depends on whether you are able to put it on a level where you can communicate with the audience.

And what is better than your personal experiences? I try to read other stories, and they are great, but they are not my stories. So personal experience is always the best place to start from. It does not start from a lie. Being a man in Kosovo, telling real and sincere stories — it’s a very good platform to promote good culture.

In one of your works as part of the “Fog” exhibition at the National Gallery you show a map where Kosovo is underwater. It’s partly inspired by your time in England some years ago, when people did not know how to locate Kosovo. Dua Lipa has maybe helped the Brits with the location but… Is it more foggy today in Kosovo? Will the fog go away?

We produce a lot of fog in Kosovo. With pollution, and literal fog. There is only one thing. We don’t have tools to remove fog and we don’t care about environmental health and political pollution, so we’re just adding more and more layers of fog. I think if you see Kosovo in ten years, the fog will be even worse because it’s mutating – layers of bad, and bad, and bad, and now it becomes ugly. If you ask me, maybe we have a more dense fog.

So how do we remove fog?

If there is fog in a valley you have to go out, take a walk, hike, climb a mountain and just watch the valley from the top and see your place from a different angle, not just from one perspective. I meet a lot of friends which don’t leave Prishtina for months. I am fortunate to have half of my family living 40 km outside the city and I go there often. I don’t just change location, I also change thoughts when I move. This study on parallel realities doesn’t just help us remove the fog, but it will also help us not to produce more fog.

In Albanian we say that the wolf needs the fog to attack, and only wolves survive in the fog. What if 90 percent of the society are not wolves and don’t want to become wolves? Because we have to have a balance of fauna in this region. What would it be if there were only wolves around? A great story to tell the kids before sleeping.K

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. The interview was conducted in English.

Feature image: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.