Since March 5, when in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH)’s first case of a person infected by COVID-19 was confirmed, 15 people have died, while more than 500 more people have been confirmed as infected.

Among the deceased is a 52-year-old woman from Sarajevo who was tested only after she had died, 12 days after her first symptoms were reported. The family of the deceased have pointed to the shortcomings in the system, due to which, they believe, their mother didn’t receive proper medical care.

They claim that as soon as they began to notice the first symptoms, they sought help from the nearby health center, requesting that she be tested. They were told that there weren’t enough tests and that they weren’t admitting patients inside the hospital. The company she worked for also reportedly filed a request for testing but even this didn’t yield results.

The family says they did what they could to help the sick woman who was lying at home but her health condition was drastically deteriorating as the days passed. After 12 days of struggle, she died as the first victim of COVID-19 in Sarajevo.

The main discussion in public life has been led by people from security institutions and politicians.

One month and 15 deaths after the first recorded case, the BiH public has barely had an opportunity to hear or see experts who could provide more information regarding the virus itself, the ways in which it’s transmitted and how citizens can protect themselves, about testing and the real capacities of the health system to respond to this pandemic.

Instead of by experts, the main discussion in public life has been led by people from security institutions and politicians, while the media provide them with unlimited space.

Simultaneously, under the veil of protecting the public from the virus spreading, the authorities are introducing numerous restrictions, demolishing the few freedoms that citizens had at their disposal.

No questions, no coordination, no logic

The BiH public healthcare system has been in a state of decay for a long time. It is fragmented in a way that reflects the complex state structure, under strict supervision from political parties. Nepotism and corruption are often linked to this system, while public hospitals and health centers are depleted to the point that they are lacking basic medication and equipment but also soap and toilet paper.

The Federation’s Union of Medics has warned of such problems in a press release, saying that doctors don’t have “adequate protection equipment, or at least most of us don’t.”

“We are on the frontlines fighting against this infection, without the basic means of protection, while the state is too slow and partially reacting,” they stated. “We are forced to self-organize as a union and to supply ourselves via our own channels to obtain the necessary protective gear.”

They added that they have filed a request for expert medical staff to be part of the various institutional “crisis teams” but it seems, to date, that there has been no response. Neither has there been criticism from health institutions or NGOs toward the government due to the way it has been handling the situation to date.

Photo: Velija Hasanbegović.

But if you decide to subscribe to everyday events in BiH, you get the sense that those in charge of deciding how to protect the population are oftentimes making decisions that are hard to grasp and which have little to do with measures to protect us from a virus of any kind.

A complex state structure, among other things, is a barrier to coordination and cooperation between different levels of authority, even in a non-pandemic age.

As the situation stands now, the population in the entire territory of the state must uphold a curfew — in the entities of Republika Srpska (RS) and the Federation from 8 p.m. until 5 a.m., and in the Brčko District from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m. Currently, curfew has been introduced for an unlimited time in all parts of the country.

People older than 65 are prohibited from going outside, while in some parts of the country this measure also applies to those younger than 18, no exceptions, which means that even sick children or those in need of special care have not been spared.

However, to cloud matters, the Federal Administration of Civil Protection director, Fahrudin Solak, is interpreting the imposed measures on his own terms, suggesting that children with disabilities, with certain restrictions, are allowed to go out into the yard and that they can spend time in the close proximity of their home but that parents should think about whether even this is safe “because the virus is all around us and nobody can guarantee that the kid will be safe.”

There are so many crisis staff teams that it’s difficult to count them all, and they are all publishing new measures every day, inviting the population to report those who don’t uphold them. The police are monitoring the implementation of these measures. In RS, they are doing so with long-barreled firearms.

Neither Dodik nor the other leaders have clarified how armed police can protect anybody in the age of pandemic.

Dragan Lukač, the RS minister of interior, explained that the police will not be placing their finger on the trigger. “Citizens should not be upset, but the police are ready to react if somebody were to use this situation to their advantage,” Lukač said, sending the police out on the streets, accompanied by anti-terrorist units.

The RS authorities have announced even more stringent measures.

“We will do everything. Nobody should have any doubts that we are determined to bring this to an end,” announced Milorad Dodik, member of the B&H Presidency from RS. “We will only review this on May 1. This means that the measures will be even more stringent in the months to come.”

Neither Dodik nor the other leaders have clarified how armed police can protect anybody in the age of pandemic, nor what is the role of anti-terrorist units. They have also failed to explain the costs of this police engagement to taxpayers’ pockets. However, as per the words of Lukač, the measures introduced are said to be necessary in the fight against the “invisible enemy.”

In another part of the country, Sarajevo, the Canton’s minister of interior, Ismir Jusko, also laid out his threats, stating that the police will have a “freehand” in their work, especially against those who violate self-isolation measures.

“These people deserve it,” Jusko recently told N1. “Perhaps they will enjoy self-isolation more in some of the detention centers.”

Jusko, Lukač and other politicians all use similar language, referring to war rather than pandemic. At the same time, when making public appearances, some officials have taken to wearing Civil Protection Unit uniforms, emphasizing very militant messages.

In a text published on the Open Democracy platform, Sandro Mezzandra and Maurice Stierl point to the war rhetoric of many leaders globally these days.

“State leaders liken the fight against the virus to engaging in warfare — although it is clear that the parallel is misleading and that those involved in the ‘war’ are not soldiers but simply citizens,” they write in this essay.

Accusations and threats

However, one parallel with warlike conditions does stand — both freedom of movement and speech are in danger. Among those who have experienced this firsthand is a person from Gradiška, in RS, who was served a misdemeanor warrant and a fine of 500 euros for “posting misinformation” on their Instagram profile.

According to the Gradiška Police Station press release, the social media post in question stated: “You will kill us with your media and depression, not with corona, stop talking about it already! Just stick to your news three times a day and that’s enough!”

The police tried to classify this offense as criminal but the district prosecutor instead decided that this was a violation of the RS Government’s decision on the prohibition of inciting panic and public disorder in extraordinary circumstances, which was adopted on March 16.

According to this decision, it is prohibited to “state and transmit fake news, claims that can incite panic or incite disruption of peace and order, enabling or significantly disrupting the implementation of decisions and measures of state authorities or organizations through media, social networks or similar means,” while the prescribed fine may reach 4,500 euros.

The media in the BiH Federation largely seem to have agreed to a different kind of censorship. Namely, journalists aren’t asking questions after officials address them during daily press conferences. Journalists are obliged to send any questions they may have prior to the conference taking place. The questions are then filtered and a person is asked to read them aloud.

Some individual journalists have complained, and one of the country’s many journalists’ associations has belatedly asked for the measures to be reviewed, but these seem to be the exceptions to the rule.

This measure came about after this entity’s prime minister, Fadil Novalić, openly attacked the media, and particularly the cantonal public broadcaster in Sarajevo, after they published a video, where he was seen struggling to put on a protective mask during a press conference.

Five people have been questioned and charges sent to the competent prosecutor's office for allegedly inciting panic through social media posts.

“Mrs. Jurišić,” his cabinet office directly addressed the director of TV SA through a press release, which stated she should “uphold at least the bare minimum of professional standards at this time. I’m afraid that you aren’t aware of the gravity of the situation the citizens of this state are facing.”

Meanwhile, both the police and intelligence service are monitoring the population in the Federation. The public has been told by the Federation’s police that, in this part of BiH, there is a team that is now monitoring all “criminal activities and misuses of public office, as well as panic spreading,” and that they are working on blocking social media with assistance from the entity’s intelligence agency.

By the end of March, five people had been questioned and charges sent to the competent prosecutor’s office for allegedly inciting panic through social media posts.

The state minister of security, Fahrudin Radončić, is also threatening to introduce further punitive measures, and to extend limitations to freedoms.

He has personally declared war not only on the virus but also on the thousands of migrants and refugees who are stuck in BiH. Many of them, some 4,000, are settled in temporary centers led by the International Organization for Migrations (IOM), and others in private facilities, whereas some 2,000 people, according to rough estimates, are left outside. They live in exceptionally difficult conditions, without the opportunity to maintain hygiene or buy food.

In one of his appearances, Radončić said how migrants are “the greatest hotspot of the coronavirus in BiH,” ordering the quarantining of the centers and with it a complete prevention of movement for migrants and refugees, threatening that, if people violate these measures, “the police has to physically force them to be there and prohibit their movement.”

So far, not a single person among the refugees and migrants in BiH has been confirmed to be infected.

The Coalition Against Hate Speech and Hate Crimes has explicitly condemned the introduction of such measures, referring to the existing Law Against Discrimination. However, their warning has hardly attracted any attention, not even from the media.

"Such measures will serve to stigmatize people exposed to health risks, discouraging others to report their symptoms."

Civil Rights Defenders (March 25)

Minister Radončić has announced restrictive measures against all those who aren’t “complying with isolation” and those “spreading disinformation,” as well as the possibility of criminal charges.

Repressive measures introduced in parts of Bosnia include the open publication of names of people who have been instructed by authorities to isolate due to potential or confirmed infection or close contact with those who have been infected. The authorities of the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton were the first to do this, publishing the names of people in isolation on the internet, with a clarification that they would “unburden” the local police force by doing so.

The Personal Data Protection Agency promptly responded with a warning that nobody can stigmatize people in this way. But, even after the publication of their press release, this practice has continued in other parts of the country.

Civil Rights Defenders have also stated their opinion on the issue, calling on BiH authorities (and also those in Montenegro, where an identical practice is enforced) to respect the right to privacy.

“It is a challenge to ensure protective measures in a time of a pandemic,” they said in their address. “But we believe that such measures will not contribute to the public good but will serve to stigmatize people exposed to health risks, discouraging others to report their symptoms to the competent health institutions.”

The fuss around ‘unnecessary’ testing

While the population is trying to handle the measures and the ensuing retraumatization — since they remind many of the war — no institution is trying to send encouraging messages or to give space to experts, which could also have a calming effect.

This is why no one in BiH can say for sure how many COVID-19 tests we currently have, nor who can get tested and when. The most frequent response from officials to the question on the number of tests available is “enough,” adding that only those with conspicuous symptoms can be tested, as well as those coming from countries at risk or people who have been in contact with the infected.

Fahrudin Solak, a member of the Federation’s crisis staff, doesn’t even see the point in mass testing, despite it having been recommended repeatedly by the World Health Organization (WHO).

There is an abundance of political self-promotion and politicking.

“There’s been an unnecessary fuss around this,” he said. “Did you test? Didn’t you test? Are you going to test yourself? Aren’t you going to test yourself? … If you’re tested and it’s positive, are there medications? No. Are there vaccines? No. Is there therapy? No.”

The issue of lacking medical staff has been burdening the entire region, as a consequence of mass departures of skilled and competent health care workers. At this point, BiH lacks epidemiologists and infectologists. The public knows little about whether there is sufficient medical equipment and if it’s operational.

However, there is an abundance of political self-promotion and politicking.

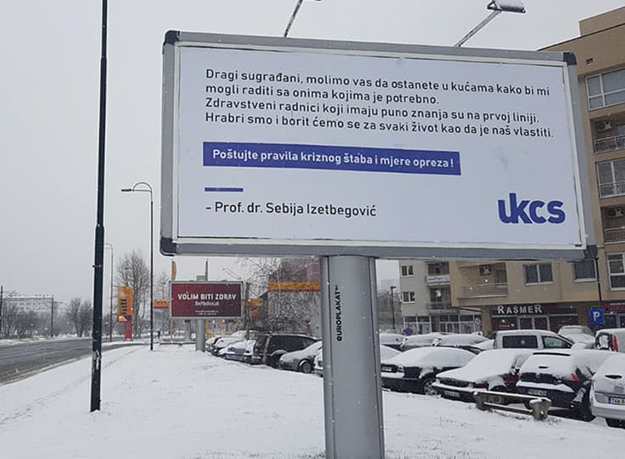

This is how doctor Sebija Izetbegović has put herself at the very center of the crisis. She is an active politician and director of the largest clinical university center in the country, based in Sarajevo, and is the wife of Bakir Izetbegović, who has been in positions of power in the state for more than 20 years.

On her official Facebook profile, one can find her interviews and statements, and a video where, with a mask on her face, in a classroom transformed into a center for patient isolation, she writes a message on the blackboard, “We are working for our citizens,” drawing a heart closeby, before walking away with a loud laugh.

Simultaneously, she has covered the city with oversize placards, containing her signature and a message to all to stay home.

Big Brother is coming to BiH

In addition to all of this, there are suggestions that BiH might soon introduce tracking and allow authorities access to people’s personal mobile phones, which is already an established practice in some countries.

Minister Radončić recently discussed this with representatives of Czechia in BiH. In cooperation with their IT experts, the Ministry say that Czechia has offered to build an application for tracking people who have been ordered to isolate, and that assistance has also been offered so that the use of this equipment would be in line with EU standards.

In a text published by the Financial Times, author Yuval Noah Harari warns that fines and monitoring aren’t the only ways to lead the population to uphold the measures which everyone can benefit from.

Our leaders are completely neglecting the recommendations and experiences of other countries.

“When people are told the scientific facts, and when people trust public authorities to tell them these facts, citizens can do the right thing even without a Big Brother watching over their shoulders,” Harari writes.

While they’re shutting down already fragile human rights in BiH, our leaders are completely neglecting the recommendations and experiences of other countries, spending valuable time that they could have and should have used for the procurement of tests, mass testing and treating the sick.

In the meantime, the population is turning toward solidarity, while they mostly find out about protective measures from foreign media. Casual cynical humor becomes one way of resisting but also venting.

But while they’re laughing at the prime minister who doesn’t know how to put on a mask, while they’re trying to count the number of crisis staff teams or figure out if there are enough tests for ordinary citizens as well as politicians, people in BiH are scared of what this pandemic might bring and what it will leave behind when it’s over.K

Feature image: Velija Hasanbegović.