Journalist Ergys Gjonçaj, from channel News 24, was filming a police action against a drug distribution group in Tirana at the end of July this year. After the police action failed, the police asked him to stop filming, and laid him on the ground to search him despite the fact that he had identified himself and his colleague as journalists.

“They kept me lying down for a few minutes and then sat me down on the stairs of a shop,” said Gjonçaj. “They took my phone. Even though I constantly repeated that I was a journalist, there was no reaction.”

According to Gjonçaj, he was not even asked for his journalist identification and was under the supervision of a police officer the whole time. The case is being investigated by the Service for Internal Affairs and Complaints at the Ministry of Interior, the agency that investigates complaints about professionalism and legal violations by the police.

Cases of police violence against journalists, and even arrests, are not uncommon in Albania. When violent protests erupted in Tirana in December 2020 after the murder by the police of a young man who had violated a Covid-19-related curfew, RTV Ora journalist Xhoi Malësia was arrested and held for several hours at a police station. In videos posted on social media, he was seen and heard telling police that he was a journalist and that he was filming the protest. After his release, he stated that the police used physical violence against him.

"Since Rama's first term, there has been a consistent line with denigrating tones, insulting language, verbal abuse and physical violence [against journalists],"

Elvin Luku

The cases of Gjonçaj and Malësia are the continuation of a deteriorating environment for media freedom and the safety of journalists in Albania. Among these active players inciting attacks on journalists there are many institutional actors, particularly from the government.

“Since Rama’s first term there has been a consistent line with denigrating tones, offensive language, verbal abuse and physical violence,” said Elvin Luku, professor of journalism at the University of Tirana and founder of Medialook, a platform that promotes a critical view of the Albanian media market.

Luku said that the language used by Prime Minister Edi Rama since coming to power in 2013 has been inciting violence against journalists.

“It started with the prime minister insulting reporters, continued with institutional violence, trying to approve anti-defamation laws or blocking journalists in the Parliament and continues with cases of physical violence toward journalists covering protests or other events,” he said.

Prime Minister Rama is now in his third term and has often been criticized for the denigrating language he directs toward media and journalists.

Ever since Prime Minister Edi Rama’s first term, journalists have operated in a hostile environment. Photo: Isa Myzyraj.

October 2017 saw one of the most flagrant cases of this animosity between the government and the media. Prime Minister Rama appeared before journalists in an unannounced conference, in front of the Albanian Parliament, and issued a stream of accusations and insults.

Rama called them “ignorant,” “poison,” “trash,” “scandalous,” “charlatans” and “enemies of the public.”

“The moment Rama thinks that an outlet or journalist is not under his control, he loses his mind like any other autocrat,” said Edlira Gjoni, communications expert in Tirana, who said he thinks Prime Minister Rama behaves like an autocrat, particularly when it comes to the media. “He behaves arrogantly in a disdainful manner, showing strength by walking out from media events or dictating to journalists with full conviction that he has the right to do so.”

The prime minister went even further on February 5, 2020, when in a post on Twitter he labeled the country’s TV shows as “sinful advocates of crime.”

The hybrid war against media freedom

Albania has a complicated history with freedom of the press. Ever since the communist regime collapsed in 1990, the press has been subject to attacks, and journalists have faced pressure, arrests, physical violence and censorship or self-censorship.

During the civil conflict in 1997, the editorial office of the country’s first independent newspaper, Koha Jonë, burned down. Media executives still accuse the then-ruling government of Sali Berisha ― Albania’s former prime minister ― of ordering the act in retaliation for the journal’s editorial stand against his government.

During the 2000s, as the country recovered from the economic crisis and political unrest, other print and audiovisual media entered the market, while foreign entrepreneurs also saw Albania as a place where they could invest in opening up new media outlets.

According to the Audiovisual Media Authority (AMA) ― an independent institution that supervises and regulates audiovisual broadcasts ― there are currently 49 televisions with a national license, two of which are currently suspended. What remains unclear is how many portals there are in Albania. As not all online media are registered, it has always been impossible to identify their exact number, but Medialook estimates there are more than 650.

But despite the rising number of news outlets, the media sector remains threatened as governments are using other tactics to put pressure on journalists.

In 2020, News 24, one of the largest news televisions in Albania, decided to close two shows that were critical of the Edi Rama's government.

In 2015, Agon Channel, a television station run by Italian businessman Francesco Beghetti stopped broadcasting after he was charged with money laundering and a warrant was put out for him by local justice. From the moment the legal confrontation began, journalists and activists in Albania saw this situation as an attack on the media by Prime Minister Rama.

After a long ordeal of international litigation, the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes ― an arbitration tribunal part of the World Bank ― finally fined the Albanian state 110 million euros in April 2021 for the damage it caused to Beghetti.

In many cases it is journalists, rather than media institutions, who have had their freedoms endangered.

In 2020, News 24, one of the largest news televisions in Albania, decided to close two shows that were critical of Edi Rama’s government.

The Council of Europe raised an alarm with the headline, “News 24 closes two critical shows,” and placed it in the category of Other acts that have shocking effects on media freedom. The Albanian government responded by saying that it was not involved in this situation, while News 24 television itself denied any involvement of state authorities in their decision.

Although Adi Krasta, one of the dismissed journalists, did not comment publicly, Ylli Rakipi, host of the other show, The Unexposed, accused the government and Prime Minister Rama of closing down his show.

There have also been legal attempts by the parliamentary majority to influence the media. A so-called anti-defamation package proposed by Prime Minister Rama and approved by his party MPs in 2019 provoked protests and strong reactions from local and foreign journalists. The government claimed the law aimed to regulate and formalize online portals, but opponents saw it as a means to control the media. The anti-defamation package aimed to amend 30 articles of the law on audiovisual media and four articles of the law on electronic communications.

This anti-defamation package mandated that the AMA would have to review within 48 hours complaints of individuals, businesses and institutions claiming that they have been defamed, or that their dignity and privacy have been violated by the media. With this package, the AMA would get the right to impose fines of up to 8,000 euros if the outlet involved failed to react.

Additionally, the Electronic and Postal Communications Authority (AKEP) ― the regulatory body in the field of electronic communications and postal services ― would place pop-ups on the websites or portals of media that had been fined. The AKEP would state in these pop-ups, which would appear every time someone accessed them, that the media or portal in question had defamed or violated the dignity of some individual, business or institution.

In the case that the publication still did not react even after having the pop-ups set, AKEP would have the power to order Internet Service Providers to block the domain, making access to the site impossible for anyone connecting in the territory of Albania.

Journalists protested against the violation of media freedom that the anti-defamation package proposed by the Rama government represented. Photo: Isa Myzyraj.

In July 2019, the Platform for the Promotion of Journalism and the Safety of Journalists in the Council of Europe called this package a threat to media freedom in Albania. According to the alert they issued, “The draft bills seek to tighten the control over online media, as the Complaints Council, which is part of the Audio Visual Media Authority, could increase censorship by ordering the removal of online content on grounds of protecting the citizens’ ‘dignity and privacy’.”

The Venice Commission ― the Council of Europe’s advisory body that provides legal advice to member states on the democratic functioning of institutions ― also criticized the power the law gave to the AMA, turning it into a court that could impose sanctions on the media when it deemed it reasonable.

In its opinion on the draft law, the Venice Commission identified Article 33/1 (4) as the most serious restriction imposed by the draft law, which specified that online media “must not incite, enable incitement or spread hatred or discrimination on the grounds of race, ethnic background, skin colour, sex, language, religion, national or social background, financial standing, education, social status, marital or family status, age, health status, disability, genetic heritage, gender identity or sexual orientation.”

According to the Commission, some elements from this list could be used to block any critical remarks against public figures or to suppress lawful political debate on issues of public interest which may be perceived by some groups or individuals as “discriminatory,” particularly regarding the expression “financial condition.”

Recently, the AMA found itself again at the center of the discussion about media freedom on the occasion of the election of its chairperson. The law on audiovisual media stipulates that the chairperson is elected with 71 votes in parliament — an absolute majority of the 140 MPs — while in the past, the candidates had to pass a series of procedures, including reaching political consensus between the ruling majority and the opposition.

However, the election of the chairperson of the AMA was the last decision of an Albanian parliament that was being boycotted by the opposition since 2019.

The newly elected head of the AMA, Armela Krasniqi, was director of Rama's communications office. Critics consider her closely associated with politics.

Despite the objections and calls from the international community, Rama’s majority and some MPs who replaced the opposition that had left parliament appointed Armela Krasniqi as the head of the most important institution for media regulation on July 7, 2021.

Krasniqi’s election was opposed not only because of the lack of opposition, which will return to parliament in September after the elections of April 25, but also because of her ties to Rama’s Socialist Party. Krasniqi, although a journalist by background, held the position of General Director of the Albanian Telegraphic Agency until her appointment, and was director of Rama’s communications office from 2013 to 2017. Critics have called her a person closely associated with politics.

The EU Delegation in Tirana made a clear call to the parliament a few hours before the vote, urging it to postpone the election of the chairperson until September.

A press release issued by the Delegation read, “We invite the authorities to consider proceeding with this nomination under the new Parliament starting in September, together with the appointment of the other board members of the Authority, in order to achieve the widest possible consensus and legitimacy.”

Five international organizations, part of the Rapid Media Freedom Response mechanism that monitors and responds to violations of media freedom in Europe, also reacted to Krasniqi’s election. They expressed deep concern about the AMA’s impartiality and future independence, considering Krasniqi a “close ally of the ruling Socialist Party.”

“The process was immoral and in violation of the Venice Commission Council,” Koloreto Cukali, chairman of the Albanian Media Council (KShM), a media union seeking to strengthen and ensure the implementation of a Code of Ethics as a form of self-regulation, told K2.0. “This commission demanded the further independence of the AMA, which cannot happen if people with party careers are placed in the leading position.”

Elvin Luku, however, sees the problem not only in the unilateral election of the head of AMA, but in the institution itself.

“The main problem is the law on audiovisual media, which disables the political independence of the institution. This [current] law guarantees an imperfect political balance,” said Luku, adding that Albania needs a non-political institution, not an institution that guarantees political balance.

The government’s infamous news practices

In the early hours of August 27, Prime Minister Rama’s Facebook profile broadcast an episode of Albanian hospitality, covering the first 121 Afghan refugees who had just arrived at the Mother Teresa International Airport in Rinas. After the withdrawal of US and other international forces from Afghanistan and the fall of the country to Taliban control, the Albanian government accepted the request of U.S. officials to shelter some of the Afghans at risk from the Taliban.

Although the media reported on the arrival of the refugees, journalists were not allowed to have cameras on the runway and were told to stay on the outer perimeter of the airport’s military runway. The images from the reception and the long queue of Afghans waiting to be registered were broadcast exclusively on Facebook from the profiles of Prime Minister Rama and the Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs of Albania.

This practice of government-exclusive coverage is not a novelty. It started in 2017 when Prime Minister Rama, in a strange move, announced that he would open his own communication channel, called Edi Rama Television (ERTV).

At that time, the head of government clearly stated that the reason for opening ERTV was to avoid the media, as he said that, “here in Tirana you intercede on behalf of third parties. The more people follow analyst debates, the less they understand what is going on.”

ERTV is broadcast mainly on Facebook while its materials can also be found on YouTube, in a channel named after Edi Rama.

Journalists were forced to stay on the outer perimeter of the military runway at Mother Teresa Airport, while exclusive footage of the arrival of Afghan refugees was transmitted from Edi Rama’s official Facebook profile. Photo: Isa Myzyraj.

Since 2017, when this channel was opened, almost every government activity is presented under the logo of ERTV, and often local media cannot access materials that are available from the office of the Prime Minister.

A similar thing happened while the COVID-19 pandemic was sweeping through Albania. The first cases were officially confirmed on March 9, 2020. During that time no media was allowed to enter the hospitals where COVID-19 patients were being treated to cover the situation, but in November 2020 the prime minister published two videos recorded inside hospitals on ERTV, labelling them as exclusive.

From March 9, 2020 to April 9, 2020, the head of government and his cabinet completely avoided media communications, yet during this time he published 407 posts on Facebook, a daily rate of 13, with 2830 video minutes, of which 2634 were live under the ERTV logo and 146 minutes of other videos. These materials dealt with coronavirus rules, press releases, legal acts, and any other means of communication with the public.

Edlira Gjoni, communications expert and lecturer in Tirana, considers the opening of this channel as a deliberate act of Rama violating media freedoms.

“It has destroyed the balance of influence in the public,” said Gjoni. “Contrary to the democratic principles of media freedom, the activity of the prime minister passes there first, through this channel, and by using the pro-government media, a curated content is injected into the public.”

"The practice where the news is prepared by the party while the media just broadcasts it has destroyed the role of the journalist as an independent reporter and has severely undermined democracy in the country."

Koloreto Cukali.

But now many institutions in Albania, as well as political parties, choose not to invite media or journalists to many events, but to prepare the news themselves and send them to the newsroom by email or by groups in WhatsApp.

Koloreto Cukali, head of the KShM union, compares this practice to Albania’s communist past, where everything was controlled by the party-state.

“The practice where the news is prepared by the party, the government and the municipality, while the media just broadcasts it, has destroyed the role of the journalist as an independent reporter and has severely undermined democracy in the country,” he said, adding that this practice resembles the Enverist model of manipulating truth at the industrial level, but with a facade that “the media is free.”

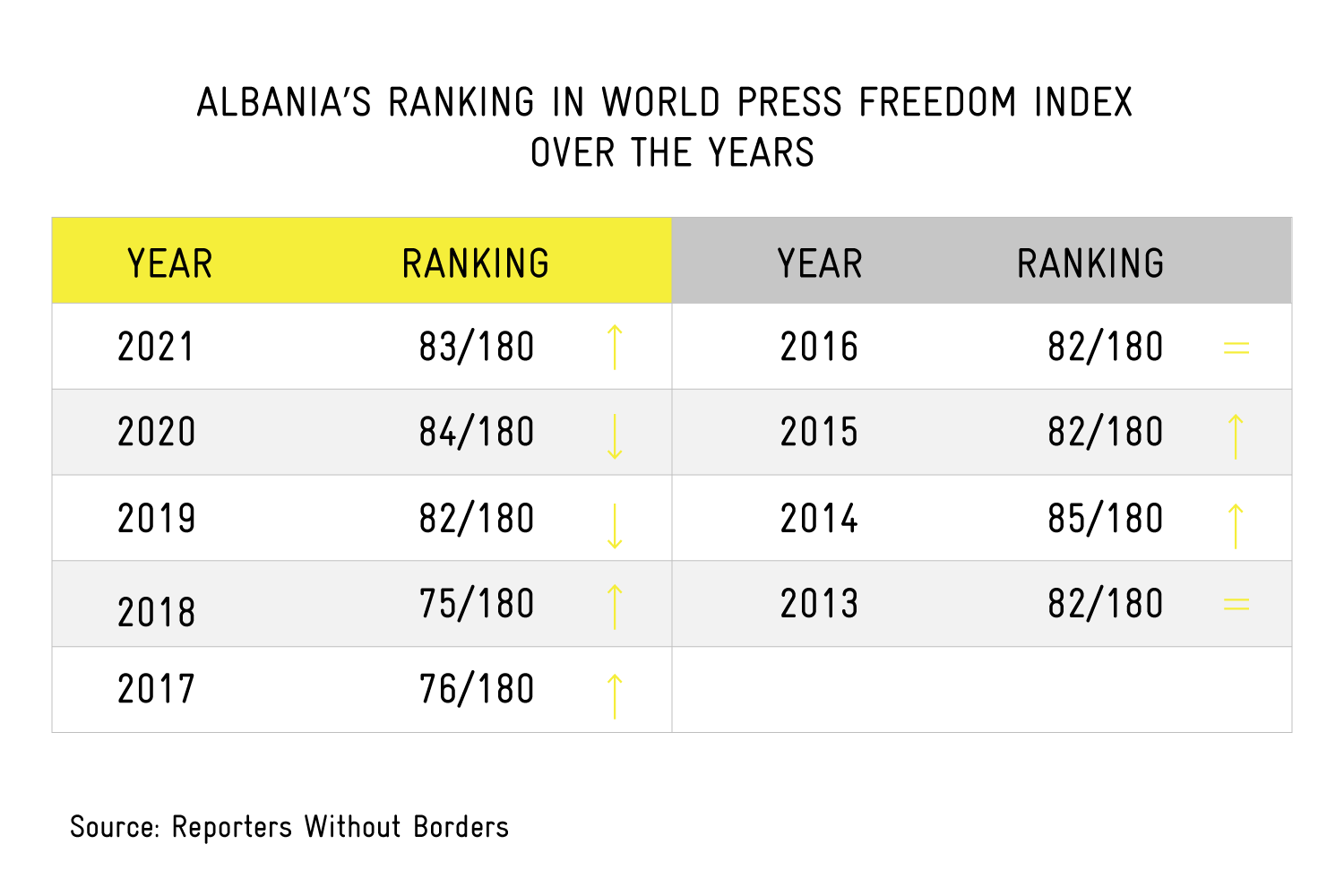

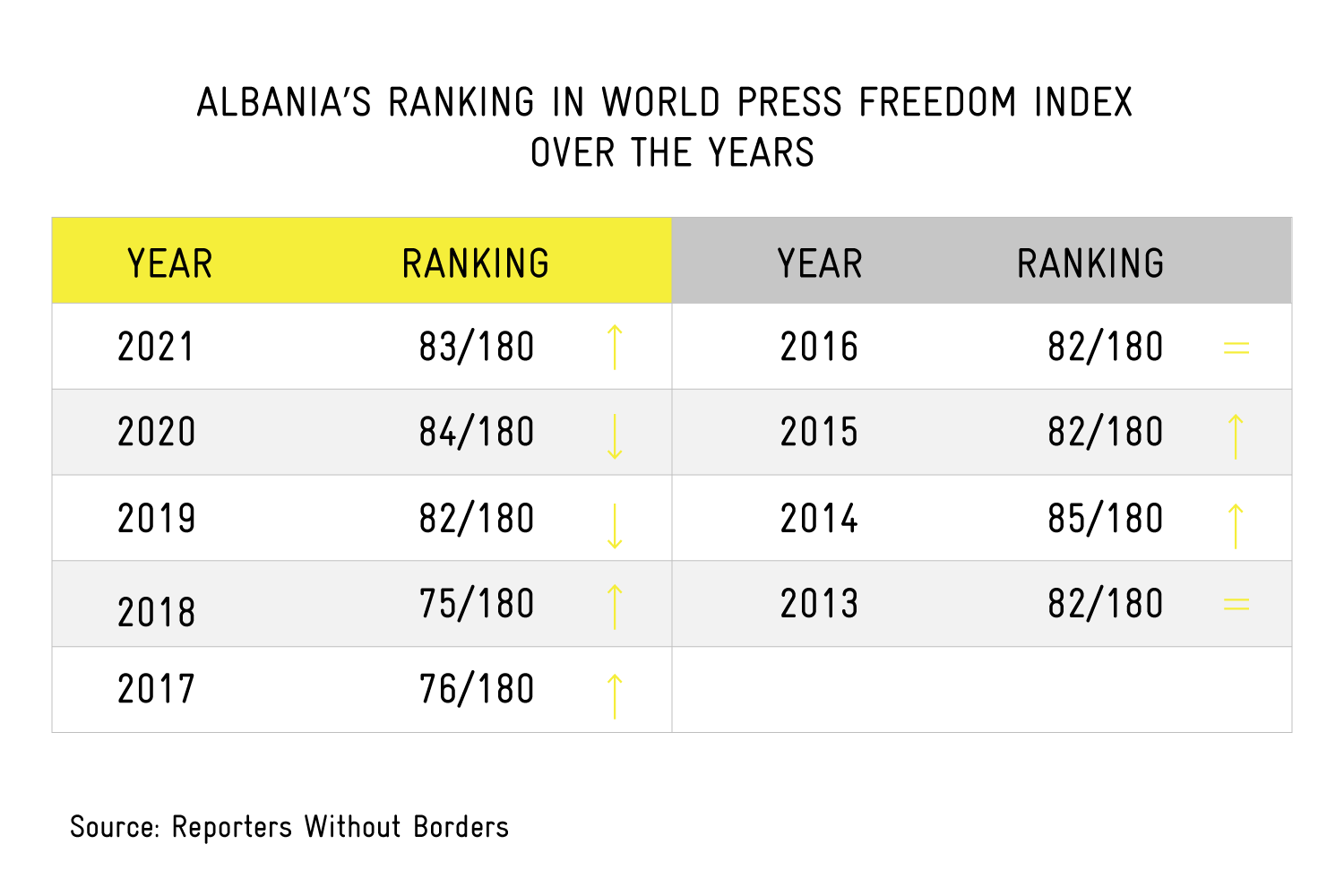

In terms of the Press Freedom Index, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) ranked Albania’s worst year as 2013, when it was 102nd out of 180 countries. In the following years, Albania’s ranking on the index has fluctuated, rising to 75th place in 2018, but falling again to the 84th and 83rd places in 2020 and 2021, respectively.

Albania was ranked 83rd of 180 countries in this year’s Press Freedom Index.

The occasional drop in international scores for media freedom in Albania is in most cases attributed to the government, which according to RSF increased pressure on the media in 2020, threatening to pass the anti-defamation law again despite criticism from media freedom organizations and the opposition of the Venice Commission.

Among other things, RSF stressed the accusations against two television stations critical to the government, Ora News TV and Channel One, the owner of which was accused of participating in criminal activities and organized crime through a special court indictment in the summer of 2020. In this case, Interior Ministry officials, accompanied by police, took control of the administration of the two canals in August 2020, claiming that their owner was suspected of drug trafficking.

However, critics also have reservations about foreign reports. The head of the KShM, Koloreto Cukali, said that they have been misinterpreted. According to him, the situation in Albania looks deceitfully better than it actually is, and there are several reasons for this. Cukali explained that due to the coronavirus pandemic, media freedom fell everywhere in the world, while some countries regressed, some even falling below Albania, and this, according to him, created the illusion that Albania was improving.

Media professionals and scholars remain concerned about the direction this profession is taking. According to Professor Luku, Rama’s practice of avoiding the media has done colossal damage, as the media, instead of providing accurate and impartial reporting, has turned into a propaganda tool for certain institutions. Edlira Gjoni said that it is the media itself that should “categorically refuse such servilism.” According to her, if the media submits, it harms its own freedom and with it, the freedom of citizens to choose and vote without being politically influenced.

The new session of the Albanian Parliament will start in September, and it remains to be seen whether the government led by Prime Minister Rama will bring the anti-defamation package back to the parliament, and how will he behave toward the media in his third term.

Feature Image: Brikena Prifti.