Landscapes of industrial ruin

Former factory workers reflect on the failed promises of privatization.

From the late ’60s to the early ’80s, factories rose across Kosovo’s cities and towns. These factories, monoliths of industrial might, employed tens of thousands of people and exported their goods throughout Yugoslavia, Europe and beyond and conveyed promises of modern progress in what was then the poorest region of Yugoslavia. They were economic pillars in their communities, and by developing Kosovo’s industrial capacity, helped nourish in the collective imagination of many Kosovar Albanians the dream of an independent republic.

For the men who labored in Kosovo’s heavy industry — and it was largely men — the factories were a source of pride and dignified work.

Today few of these factories remain. Many have been abandoned, emptied, gutted, transformed into landscapes of industrial ruin, or in some cases, into supermarkets, warehouses or other uses. Though a decade of Belgrade’s oppressive and deindustrializing policy in Kosovo that culminated with the ’98-’99 war caused significant damage, many managed to make it through that period. What the factories couldn’t survive was the post-war privatization.

When privatization began in Kosovo in 2002, it was presented as an unavoidable necessity in the international state building process. International actors, primarily the U.N. Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) and the World Bank, promoted privatization as the key that would unlock economic growth and entry into the pantheon of Western free market liberal democracies.

Since then, it is estimated that over 75,000 people lost their jobs as a direct result of privatization. Critics have long argued that citizens were excluded from the process and that there was never any substantive discussion about alternative strategies to privatization that may have offered a chance to revive the industrial economy. Moreover, the process has been clouded in allegations of corruption; and many of Kosovo’s 600 or so socially-owned enterprises were sold to a small group of business people at artificially deflated prices.

Among the most affected from privatization have been former factory workers who found themselves struggling to find their way in the new postsocialist economy. The nostalgia many of these workers feel for the era of socialist industrial labor may come across as a tale of a romanticized and mythic lost past, but the sense of security, purpose and agency they felt working for socially-owned enterprises with robust social welfare provisions was far from a myth. This nostalgia is perhaps heightened by the mass unemployment and social dispossession that has followed.

Kosovo’s current government has announced they aim to break with the two-decade long legacy of privatization by establishing a sovereign fund to manage state assets. In this moment of political shift, some of Kosovo’s former industrial laborers reflect on what was lost to the era of privatization.

It was a good life for the time

When Ruhan Kadriu decided to put himself forward for a new job after he had spent nearly 16 years as a finance officer at the “Fabrika e Armaturave të Ndërtimtarisë – FAN” (“Construction Rebar Factory”) in his hometown Podujeva, deep down he hoped he wouldn’t get hired.

Located around 200 meters from his house, the factory had been his second home since 1985, when he began working there as an intern two years after the factory opened. As one of its long-serving workers, Kadriu was fortunate enough to live what would later be remembered as the factory’s golden era. Those were the days in the mid to late ’80s when trucks from all over Yugoslavia would line up in front of the factory’s gates to receive their loads of rebar and welded steel mesh panels.

The factory was a branch of Zenica’s metallurgical combine, one of the largest in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Podujeva branch’s 50,000 tons of refined steel products were shipped across Yugoslavia and exported to Greece and Italy.

Kadriu was often tasked with financial duties that required him to travel all over Yugoslavia to meet with the factory’s business partners. “I was almost always on the road,” he recalled.

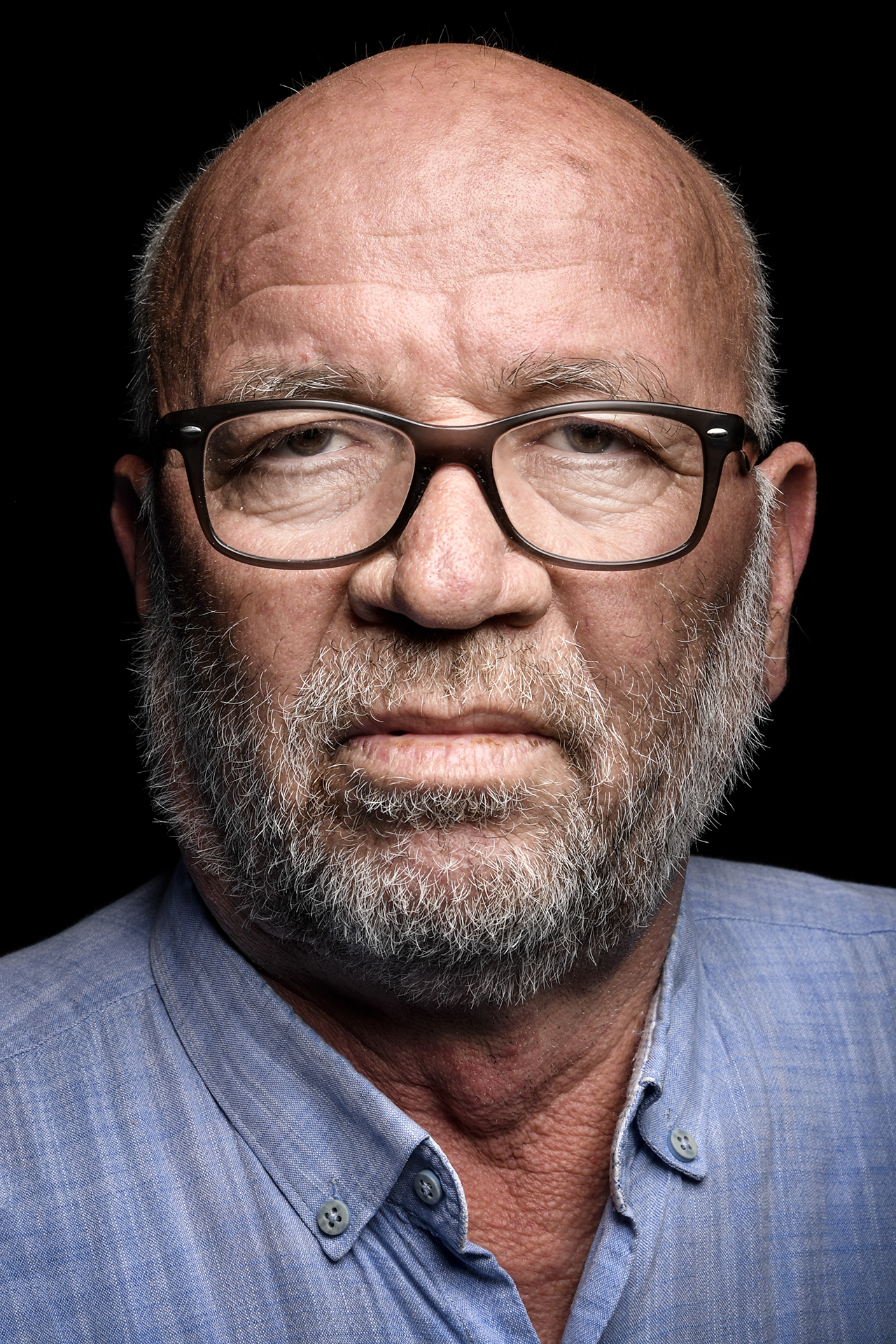

Ruhan Kadriu: "There’s no one on this earth who can convince me that privatization brought any good to this country."

"Workers who had been there for 20 years bought into the illusion that privatization would make the factory blossom."

Employing more than 350 workers, the factory played a central role in Podujeva’s economy. “The whole town rejoiced each time the factory workers got their monthly pay,” Kadriu told me. In addition to a good salary, the factory provided other benefits characteristic of the socialist Yugoslav system: health insurance and free vacations. Each summer, the workers went to Neum, a coastal town in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the Zenica combine had a hotel. Three of the rooms were reserved for workers from the Podujeva factory. “We would take turns so all of us could use the rooms,” Kadriu said. “It was a good life for that time.”

In 2001, when Kadriu applied for the new job, the rebar factory was no longer the stately “metallurgical giant” it once used to be for Podujeva. A decade of political turmoil, culminating in the 1999 war in Kosovo, had tarnished its shine.

Nevertheless, the situation was not completely desperate. Two years after the war, some kind of normalcy had settled in and workers began to return to the factory, production started up again and there was even enough revenue to afford paying decent wages. “At some point after the war, I had a salary of 800 Deutsche Marks,” Kadriu said.

Kadriu was among the first workers to enter the factory in June 1999 just a couple of days after NATO troops arrived in Podujeva.

So on a day out with friends in Prishtina, when Kadriu saw the job vacancy announcement, he hadn’t been considering changing the course of his career. It was a finance officer position at the Department of Social Welfare, in what were then the provisional institutions established by UNMIK. “I applied mainly out of curiosity,” Kadriu said. “But I wasn’t thinking of leaving the factory at the time.”

Back in June 1999, Kadriu was among the first workers to enter the factory just a couple of days after the early morning when NATO troops arrived in Podujeva, bringing glad tidings of liberation. Inside the factory, he and some of his colleagues found a significant amount of raw material that allowed them to commence production. “The factory was lightly damaged during the war and we gathered day after day to clean it,” Kadriu remembered. “Soon we managed to revive the factory and that kept us going.”

However, it would not take long for the initial enthusiasm to wane. According to Kadriu, day-to-day disagreements between the workers and the managerial staff started occurring. He claims that qualified workers began to leave, and the least experienced took over. Soon, talk of privatization was in the air. Whether cynically planned or not, Kadriu thinks that the shop floor rancor and discontent helped depreciate the value of the factory. This made privatization seem acceptable, even desirable. “Workers who had been there for 20 years bought into the illusion that privatization would make the factory blossom,” he said.

It was then that Kadriu — today the director of Internal Audit at the Ministry of Finance, Labor and Transfers — felt fortunate he took the job at the Department of Social Welfare. He had been working for some time both there and at the factory. As divisions among the workers deepened and privatization was presented as the only salvation, it was clear to him that he had no future there. “All our hard work, all the capital and the assets were suddenly sinking,” Kadriu recalled with anger.

The rebar factory was ultimately privatized in 2006. A businessman from Podujeva, Agim Deshishku, bought it for 2.3 million euros. For Kadriu, the selling price was an outrage. Though the workers never tallied an exact estimate of the factory’s real value, Kadriu thinks that with the seven hectares of land and all the machines that it owned, it was worth as much as 20 times what it was sold for.

The factory was among 24 socially-owned enterprises privatized through the “special spin-off” method that required buyers to maintain the previous activity of the company, make a set of investments and employ a certain number of workers. Based on the contract, Deshishku was obligated to invest 2.8 million euros and employ 236 workers in the factory.

Along with failing to fulfill the contract’s conditions, in 2014 Deshishku was arrested for fraud, tax evasion and legalization of false content, all in connection to his activities with the factory between 2006 and 2012. As part of the case, officials from the Privatization Agency of Kosovo, members of its management board and employees of the Cadastre Office in the Municipality of Podujeva were charged with fraud and abuse of office.

In 2019, Deshishku was found guilty of fraud and tax evasion and was obliged to pay damages of nearly 54,000 euros to the Tax Administration of Kosovo, though he was acquitted of legalization of false content. The other accused parties were found not guilty. However, in 2020 the Court of Appeals sent the case back for retrial. Deshishku again stands accused of legalization of false content while the others stand accused of abuse of office.

Meanwhile, in 2008 Deshishku mortgaged the factory to Raiffeisen Bank and then failed to meet loan obligations. He has been involved in a lengthy legal fight with the bank over the ownership of the factory. Raiffeisen Bank stated in an email to K2.0 that the bank has not been confirmed yet as the owner of the factory due to a long-term restraining order issued by the Basic Court in Prishtina.

Beyond the rusted fences, only a stray dog with her puppies and a bored guard wander around.

Deshishku was also sued by the factory’s union at the Special Chamber of the Supreme Court. The union claimed that he did not pay the workers according to the employment contract and pressured them to leave the union. An article published by Preportr in 2012 states that the workers claimed they were fired in retaliation for striking against unfair treatment, such as late payment of salaries and coercion to do work outside their contracts.

For nearly a decade now, the Podujeva rebar factory has been closed. Beyond the rusted fences, in the lane that leads to the factory’s entrance, only a stray dog with her puppies and a bored guard wander around.

But another picture floats in Kadriu’s memory, a more vivid one, of how the place used to be. “Every morning the workers lined up at the entrance, waiting to check in. We would go around 9 a.m. to the cafeteria, which was over there on the left,” he said, pointing from outside the fence. “The production floor was on the right.”

“There’s no one on this earth who can convince me that privatization brought any good to this country,” Kadriu continued, as the guard listened from the other side of the fence. The guard, who also used to work in a public enterprise, though dutifully fulfilling his job to deny us entry to the locked up factory, seemed to think similarly. “None of us,” he said, “would be here today at these closed gates if it weren’t for privatization.”

They’ve taken down the factory signboard

In the early ’70s, Ramadan Ahmeti returned to his hometown Prishtina for the holidays after having spent three and a half years working at a Peugeot car factory in France. He was one of 60 workers from Kosovo who had been sent by the Office for Incorporation — a socialist state organ that dealt with employment policies — to undergo professional training in France.

Skilled at assembling cars, Ahmeti had a steady job and a good salary at the Peugeot factory and were it not for his father who begged him to stay in Kosovo, he would have taken the train from Fushë Kosova and returned to France. Instead, he headed to the train station only to hug his work friends goodbye and, complying with his father’s wish, embarked on a job hunt in Prishtina.

Ahmeti got the job, but he never stopped craving the adrenaline of the noisy factory floors.

At the time, Radio Television of Prishtina (RTP) — the first Albanian-language television broadcast in the country — had just begun operating. So when Ahmeti met with a local labor union leader to ask for a job, he suggested Ahmeti apply there. Ahmeti got the job, but he never stopped craving the adrenaline of the noisy factory floors. “In France, the factory produced up to 1,600 cars in a day, and I assembled all Peugeot models, from the 104 to 504,” he recalled. “That’s what I was trained for and what I wanted to do.”

He soon read in the newspaper that the “Fabrika e Amortizatorëve” (“Shock Absorber Factory”), located on the outskirts of Prishtina, was looking for around 150 workers. Ahmeti went straight to the factory’s director and with his experience he was quickly hired.

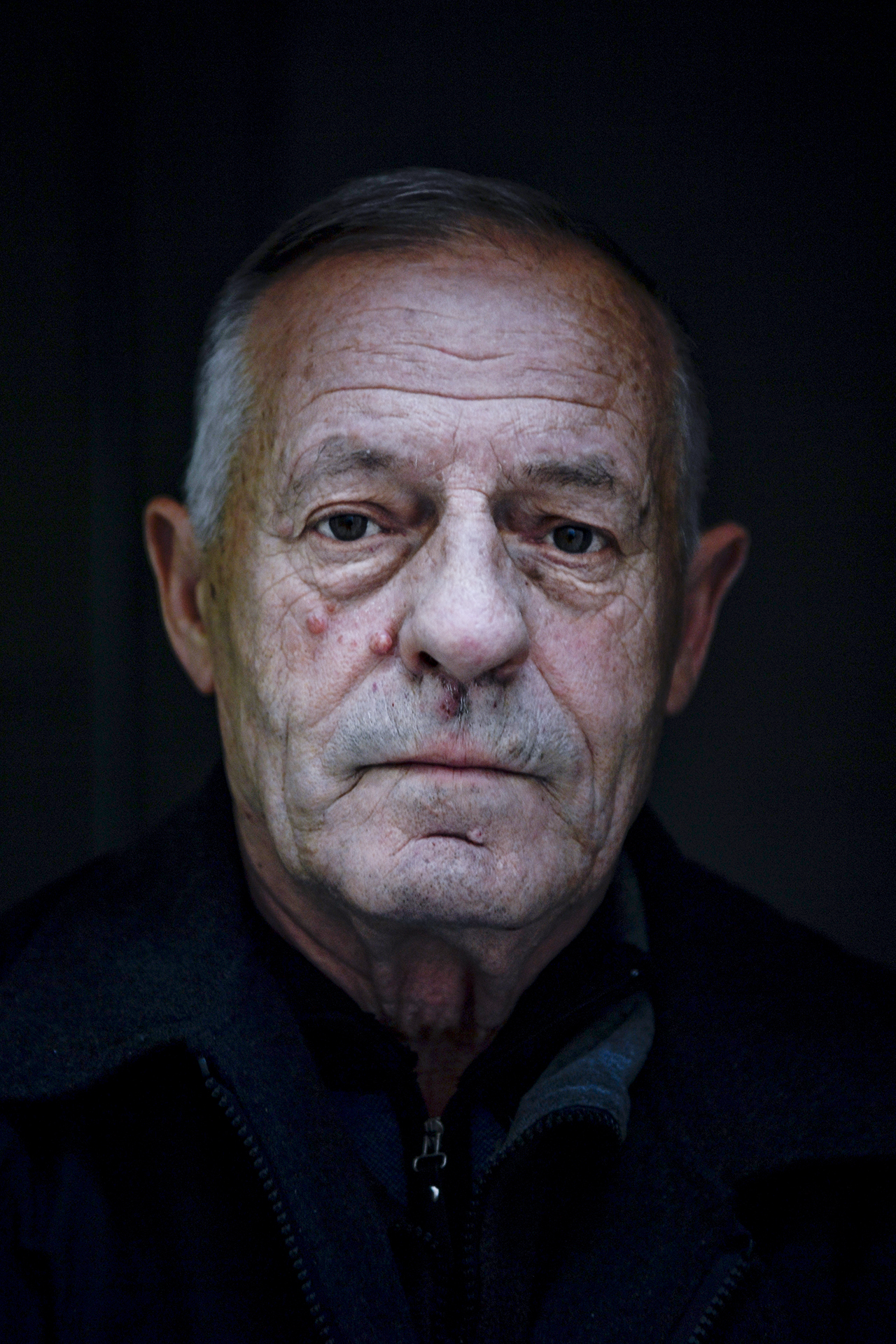

Ramadan Ahmeti: "We came back with the idea to resurrect the factory and employ our children there."

"They recently removed the factory’s signboard and don’t allow us to go inside the site."

On his first day of work, the factory seemed to Ahmeti like a miniature compared to the Peugeot factory in France. “The factory gave me the feeling of a small warehouse when I first entered,” Ahmeti recalled. He had been used to endless factory floors, where he could get lost going from one production line to the other.

The Shock Absorber Factory was among the biggest factories operating in Kosovo at the time. With over 1,600 workers, it was the only factory in the region producing a wide range of shock absorbers for washing machines, cars, buses, airplanes, trains and military tanks. Monthly production reached over 300,000. “We used to produce shock absorbers for all kinds of vehicles in Yugoslavia,” Ahmeti said, adding that large car manufacturers, such as Mercedes-Benz, Peugeot and Zastava were also among their regular clients.

In addition to shock absorbers, the factory produced parts for different military weapons — pistols, automatic firearms, mortars — mainly for the Yugoslav People’s Army.

Ahmeti worked on different production lines until 1989, when, together with the vast majority of Albanian workers, he was forced out of the factory following the announcement of “special measures” — the Milošević regime’s response to increasing tensions in Kosovo, and the beginning of the long hard ’90s. It is estimated that 145,000 Albanians were fired from positions in public institutions and economic enterprises during that period.

He returned to the factory after the end of the war in 1999 and was surprised to find the warehouses full of finished products. “We came back with the idea to resurrect the factory and employ our children there, since a lot of the workers were near retirement age,” Ahmeti said. “So, we were glad to see that production had not completely stopped.”

In 2001, the European Agency for Reconstruction listed the factory as one of five enterprises in Kosovo with the greatest potential to recover, while a 2016 BIRN report stated that it was “an excellent example of successful efforts to re-initiate production after the conflict.”

However, the story took a different turn. Ahmeti — who now is the head of the Shock Absorber Factory workers’ independent trade union — claims that the factory’s board began embezzling funds and improperly selling off factory assets.

What followed was a decade of mismanagement, low salaries and violations of the workers’ labor rights, culminating in the 2010 privatization of the factory. “None of the workers were informed when the factory got privatized,” Ahmeti said. “We were forcefully taken out of our workplace without any decree or prior notice.”

The factory and its over eight hectares of land were sold for just over 2 million euros to the Devolli Group corporation, which is widely considered to have monopolies in many sectors of Kosovo’s economy. The factory’s administrative building was privatized separately and purchased for just over 5 million euros by a company with close ties to Devolli.

In addition to the low selling price — the labor union valued the factory’s movable assets alone at 93 million Deutsche Marks — there were a number of procedural violations in the privatization process. Though the tender procedures required at least three bidders, the Devolli Group won the tender even though their bid was the only one. Moreover, at the time when Devolli bought the factory, the owners of the company were being investigated by EULEX for fraud, breach of trust, forgery of documents and organized crime. The rules of the Privatization Agency of Kosovo (PAK) specified that bidders with indictments would be disqualified from the outset.

The buyer also failed to comply with the contract’s requirements. The factory was sold through the special spin off method, meaning that the new owner was obliged to maintain the same economic activity for at least the next five years, which did not happen.

A decade after its privatization, almost nothing is left of the old factory site.

In a 2014 parliamentary debate about the privatization of the Shock Absorber Factory, Visar Ymeri, then a member of the Assembly for Vetëvendosje, said: “This is the best illustrative example of how the privatization process has carried on and what damage it has caused to the economic potential of the country. From being a manufacturing plant, the factory has been reduced to mere buildings and land.”

In his speech, Ymeri also referred to a report that the Shock Absorber Factory workers’ union submitted to the Assembly, which claimed that the factory owners appropriated around 1,000 movable assets from the factory and sold them for 7 million euros, even though those assets were not initially part of the privatization deal.

A decade after its privatization, almost nothing is left of the old factory site. Younger generations might not know that the current offices of Klan Kosova — one of the largest private broadcasting companies in the country — and a customs terminal owned by the Devolli Group, are where the factory that symbolized Kosovo’s production power and industrial development used to stand.

“They recently removed the factory’s signboard and don’t allow us to go inside the site,” Ahmeti said.

Despite the workers’ frustration and disappointment, their marathon fight for, as they put it, “compensation for all the sweat of our youth we left on the factory floor” is far from over.

Surrounded by piles of documents — most of them yellowed and torn at the corners — Ahmeti picks up the union’s latest complaint submitted to the Ombudsperson Institution. The workers, 496 of them, are demanding to receive the full amount of the 20% of the sale proceeds from the factory’s privatization that is their legal due.

According to PAK’s rules, workers are entitled to 20% of the earnings generated from the privatization of previously socially and publicly owned enterprises for which they used to work. To date, the Shock Absorber Factory workers have received 627,476 euros of the 1.4 million euros they are owed from the factory’s privatization.

They are still waiting for over 800,000 euros. However, this amount might be distributed to 676 workers rather than 496, as was initially planned, since around 180 more workers — primarily Serbs — have been added to the beneficiary list. Ahmeti and the workers’ union are opposing this decision, claiming that these workers did not work at the factory after 1999, which was one of the conditions necessary to be fulfilled in order to be added to the beneficiary list.

Among other requests, the workers are asking to receive their monthly salaries from the last seven months of work at the factory, which have still not been paid a decade later.

While PAK’s bureaucratic procedures and court cases regarding the factory’s privatization have turned into a never-ending saga, the everyday lives of many of the workers are caught up in a constant struggle against poverty. “We have found ourselves in an abysmal economic situation, drifting from one insecure job to the other. Tell me, how would you feel encountering your former colleagues begging or collecting scrap metal on the streets?” Ahmeti asked. Then, he answered himself, “I don’t think there’s a worse feeling than that.”

We will buy the factory ourselves

In 1973, Nebi Jashari became the second Albanian mechanical engineer employed at the IMK Steel Factory, known as the “Fabrika e Gypave” (Pipe Factory), in his hometown Ferizaj. The ten other engineers working at the factory, opened just a year earlier, were Serbs.

Jashari had just returned from Rijeka, Croatia, where he had studied on a state scholarship. In the late 1960s there was no mechanical engineering program at the Technical Faculty in Prishtina so Jashari, along with four other Albanian students from Kosovo, went to study in Croatia. “We first wanted to enroll in Zagreb, but we missed the application deadline. Rijeka was the second option,” Jashari said.

Upon his graduation, he was first appointed to work at the Kosovo Energy Corporation (KEK) in Obiliq, but was then transferred to the Ferizaj Pipe Factory, which had around 1,300 workers. The factory was built as part of the Smederevo metallurgical combine, which produced the raw steel that was later refined into pipes of all sizes in Ferizaj.

Nebi Jashari: "There was a big feast in Ferizaj on the day the factory was opened."

"The period after privatization is quite distressing. Sometimes you have to suppress some of the emotions in order to move on."

“The Kosovo market was too small for the factory’s production. We had contracts of over 20 million dollars with the U.S and Turkey,” Jashari said, adding that they also exported to the Soviet Union, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Italy.

In his eight years at the Pipe Factory, Jashari would work in a variety of different positions and slowly climbed the managerial ladder to become technical director, and he often traveled back to Croatia for work and his graduate studies.

In 1981, he was with some of his colleagues at the Zagreb Autumn Fair when the idea arose among them to build a new factory in Kosovo. Jashari met with managers from the Croatian metal engineering company Đuro Đaković and discussed how to make best use of the Federal Development Fund that was distributed to the less developed parts of Yugoslavia — Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia and Montenegro. According to a 1979 World Bank report, between 1971 and 1975, 70% of the fixed asset investments in Kosovo came from financial resources transferred from the Federal Fund.

Jashari and the Đuro Đaković managers came up with a proposal for a new factory that would manufacture heat exchangers, systems used to transfer heat between two different liquids necessary for industrial production. It took no more than a year for the factory to be erected. “There was a big feast in Ferizaj on the day the factory was opened,” Jashari recalled. “I’m still emotionally connected to the factory since I took part in each phase of its design and was appointed its first director.”

Employing around 200 workers, the factory was initially supposed to produce for the needs of the Kosovo C power plant, which was meant to generate electricity for Yugoslav republics outside Kosovo. However, the Kosovo C power plant was never built and the factory ended up producing heat exchangers, metalwork and irrigation equipment for the Trepça mines, KEK and the cement factory in Hani i Elezit. They also exported to Croatia and Vojvodina.

Jashari served as the factory’s director until the end of 1988 when he was forced to leave by local officials who claimed that Serb workers did not want him as a director. “The decision was very painful for me,” Jashari said, adding that Serbs comprised only 15% of the total factory workers.

"The workers were afraid they would end up jobless, but were lured by the buyer." Nebi Jashari.

He went on to work in an engineering bureau and returned to the factory a decade later in the summer of 1999, again as a director. “The windows were all broken from the bombing and most of the machinery was not functional when we came back after the war,” Jashari said. “But with 60,000 Deutsche Marks we received as a donation from the IOM [International Organization for Migration], we managed to repair more than 20 machines and buy new ones, install heating and open the cafeteria inside the factory,” he added with pride. The factory restarted operations almost immediately, producing mainly for the needs of KFOR, Camp Bondsteel and the Post of Kosovo.

Despite the factory’s revival, the seemingly inevitable wave of privatization arrived in 2005. According to Jashari, there were no discussions about privatization.

“Factory managers were pressured to accept privatization as inescapable,” he said, adding that a variety of forms of pressure were used on them and on the union. “The workers were afraid they would end up jobless [after privatization], but were lured by the buyer. There were already rumors in the air about who would be the new owner.”

Jashari had tried to organize the workers to buy the factory themselves, but his ambitions failed. “In a meeting of the workers’ council, I said: ‘We will buy the factory ourselves. Whoever wants, is invited to invest as much as they can afford.’” However, the workers who for around 20 years had put their time and energy into the factory, didn’t have the capital to buy it. “Are you asking us to sell our houses?” they had asked Jashari.

The factory along with the land was privatized in 2005, purchased for around 1.5 million euros by Sami Musliu.

Even though the factory did not close and to this day continues to operate, Jashari notes that not all the workers kept their jobs. “Out of 10 engineers who used to work at the factory, only two of them are still employed there,” he said.

Jashari went on to work as an engineer in private enterprises, but he adds that many of his colleagues became jobless in the capitalist market economy. “They now receive a pension of 70 to 90 euros.”

His colleagues at the Pipe Factory have had an even more arduous experience. As of 2018 they had held around 130 protests and their over 600-day strike is one of the longest ones in postwar Kosovo.

For almost 20 years, the workers have been fighting against the privatization bodies over a 2002 decision by the Municipal Court of Ferizaj that granted them the right to receive over 25 million euros as compensation for their forced dismissal and the loss of wages during the period between 1989 and 1999. The executive board of the factory had approved the request but since they did not have enough funds to compensate the workers, they said they would issue securities instead. That meant workers would have the right to become shareholders in the company if ownership changed hands.

However, the 912 workers never received any form of compensation, which led to five years of back and forth court claims filed against each other by the workers’ union and the pre-2008 internationally run privatization agency, the Kosovo Trust Agency (KTA). This continued until November 2007 when police entered the factory and prohibited the workers from continuing to work there. A day after, KTA announced that the factory had been privatized at a price of 3.6 million euros, despite the workers’ rejection of the process as illegal and arbitrary.

The former workers of the Pipe Factory gather almost every Monday in the main square and share news about their fight.

In 2010 the Constitutional Court ruled that the 2002 decision of the Municipal Court of Ferizaj must be carried out and it seemed the workers’ union had won the case — the government and PAK were being held liable to pay out the compensation. But the 2002 decision has never been implemented, leaving the workers no other course of action than continuous protests in front of government buildings and in Ferizaj.

In 2019, the then President of the Constitutional Court, Arta Rama Hajrizi, sent a notification letter to the Chief State Prosecutor stating that the “case cannot yet be considered fully closed and completed as the decision of the Court remains unimplemented by the responsible bodies” and asked the prosecutor to address the issue.

To this day, the former workers of the Pipe Factory gather almost every Monday in the main square of Ferizaj and share with each other news about their fight.

“The period after privatization is quite distressing,” Jashari told me. “And the case of the Pipe Factory workers is among the most painful ones. Sometimes you have to suppress some of the emotions in order to move on.”

Salvaging what’s left

In late May 2021, the privatization process was upended. In a tense meeting, the Assembly voted to dismiss PAK’s board, a first step in closing the agency.

Calling the last two decades a “period of economic alienation and deindustrialization,” Prime Minister Kurti said the dismissal was a step toward establishing a Sovereign Fund, a body that intends to manage state assets for the common good and a long running Vetëvendosje electoral promise.

According to the current government’s 2021-2025 program, the Sovereign Fund is meant to “take ownership of strategic assets of the Republic of Kosovo, valorize them and allow for foreign investment and access to foreign capital markets.”

The head of the recently formed working group to establish the Sovereign Fund is Besnik Pula, a professor of political science at Virginia Tech University whose research focuses on the comparative political economy of states in Central and Eastern Europe. In a statement to K2.0, he said that the Sovereign Fund represents a new model of strategic asset management and that it will rely on an investment fund rather than on ministerial agencies and commissions.

The Sovereign Fund aims to reverse the economic model centered around the idea of privatization that has dominated since the postwar period.

“International experiences show that such a model is much more effective than the current form, in terms of improving the management quality of enterprises, their financial performance and offering them access to sources of capital,” Pula said.

Public enterprises that currently operate as joint stock companies under the Ministry of Economy — such as Trepça, the Kosovo Energy Corporation, Kosovo Telecoms and the Kosovo Post — are marked to be given over to the Sovereign Fund, as well as a number of currently dysfunctional or unused assets administered by PAK.

Considered by Kurti as “one of the largest economic reforms in the country since the declaration of independence,” the Sovereign Fund aims to reverse the economic model centered around the idea of privatization that has dominated since the postwar period.

On January 17, the working group submitted a concept document to the government, laying out the structure of the fund, though the document is not yet available to the public.

Though the idea for the establishment of the Sovereign Fund carries the promise of a rupture with the two-decade long privatization process, the factories lost to privatization will go on weighing heavily in the lives of former workers, and in the collective memory of the country.

Feature video: Sovran Nrecaj / K2.0.

![]()

![]()

This story has been produced with the financial support of the “Balkan Trust for Democracy,” a project of the German Marshall Fund of the United States and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Opinions expressed in this story do not necessarily represent those of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Balkan Trust for Democracy, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, or its partners.

- This story was originally written in English.

I remember passing by the FAN factory during the latest years in my hometown Podujeva, and it's like a ghost place. It makes me feel homesick, even though I have no experience there. I can't imagine how it is for the former workers... A place in decline, rather than being the opposite now.