As years go, 1983 was rather uneventful in Albania and its summer sleepy. But in hindsight, just how quickly and thoroughly the country would change only a few years later was perhaps forewarned one late morning that June, when a young man drove off in a government car down the main avenue of my neighborhood, Myslym Shyri Street. He skirted the sidewalks left and right, wheels screeching, ultimately slamming the belching car into a plane tree next to Rriku’s newsstand at the end of the street.

Halfway through the joyride, and right in front of the movie theater, the Polish-made Fiat swiped the bicycle cart of the neighborhood’s ice cream man, our Gega, knocking him over. His four canisters of ice cream smashed on the ground with a blast. Curious onlookers thronged. Then came the sirens, the investigators and the ambulance that took the graying man to the hospital.

It was the Tirana of 40 years ago — the few cars that existed served party bosses and government officials, so the rumor that a car-gone-mad had run Gega down, scoop in hand, spread through the neighborhood like wildfire.

Who knows if that distant memory would have resurfaced if three years ago I hadn’t seen a photo of the ice cream man on one of those Facebook pages that ooze with nostalgia? This one focuses on late Communist Albania and is named “Na ishte dikur” in Albanian, “Once upon a time.”

In the photo, Gega is shown pushing his cart on Tirana’s central square and a young girl walks towards him with an ice cream cone in hand. A giant portrait of Enver Hoxha, hanging from the colonnade of the Palace of Culture, looms in the background. It looks like a glossed mise en scène for the period’s propaganda magazines.

Half of the hundreds of comments under that Facebook post were in loathing of the dictator and half in longing for the ice cream man. The post itself was shared 200-odd times. Hoxha and Gega were two of the main fixtures of my childhood, so I shared it too.

“Do you recall when that car hit him?” a neighbor wrote when he saw my re-post. I did not. I hadn’t even been aware it happened. But when my neighbor mentioned it, I began to reconstruct the story and the world it came from. What happened to Gega, I wondered? Who was he? Did he — did these guys — have a name even?

Three or four generations worth of kids had known him as the tall Gega, the tall Gheg, to distinguish him from Ali, the short, plump one with whom he’d shared the territory. There were quite a few of them in town and we called them that because they came from the north. Albanians are divided between Tosks in the south and Ghegs in the north, but from Tirana on down to the south of the country, when we said Gega it was not the origin of these people we had in mind. It had become the generic name kids had for ice cream men and peddlers of sweetmeats.

Moreover, the Gheg dialect — the Albanian of Kosovo, northern Albania, Montenegro, and North Macedonia — with its soft R’s and nasal vowels chewing up participle endings, was not how they spoke, or at least most of them didn’t. Our ice cream man’s participles were complete and his baritone A-koo-llo-RRREY! rolled and boomed.

Most Gegas were not born to Albanian-speaking families. They were Goranis, a community of Muslim Slavs from the high plateaus and remote valleys on the borderlands of present day Albania, Kosovo and North Macedonia. We’re talking here about 29 villages, a few tens of thousands of people, in a patch of the Sharr mountains between Kukës, Prizren and Tetovo.

Their language — they call it “našinski,” that is, “ours” or “our language” — is closest to western Macedonian dialects, but with distinct grammatical features and peppered with Serbian, Albanian and archaic Turkish words. During the Ottoman period, they were a pastoral community that would take their flocks as far south as the plains of Thessaly for the winter. According to oral tradition, brigandage then forced some to give up herding and move to urban areas where they practiced wrestling and sold boza, roasted nuts or halva in the market.

Of halva and wrestling

But it might have been simply overpopulation that forced many Gorani men to wander the Ottoman orbit for work. “Theirs was a seasonal migration,” Thomas Schmidinger, an Austrian ethnologist, told me. Men would ritualize their departure around the day of Saint Demetrius in October, making sure to be home for Djuren, Saint George’s Day, in late spring. Summers were a time for plowing the land, dealing with livestock, marriages and circumcision parties accompanied by wrestling performances.

During this seasonal labor migration, which they referred to with the Turkish word “gurbet,” they were known for being street-food peddlers: roasted chickpeas, grilled tripe, calf liver cubes and kebabs. With time, they became associated with beverages, ice cream and pastries.

It may have been in Prizren — nestled up against the Sharr’s foothills and the center of the regional market — that the Goranis first established their reputation for sweets and refreshments, food researcher Jeton Jagxhiu told me. Well into the 1950s, one family of confectioners had a snow-storage pit — essential to making ice cream and cold soft drinks in the summer during the pre-refrigerator era — in their courtyard. Not long ago, the town numbered about a dozen Gorani pastry shops.

A Muslim man sells candies in Ottoman Prizren. Photo: Auguste Léon, Musée Albert-Kahn.

A World War I-era census showed that nine out of ten of the 1,800-odd Gorani men were pastry-makers. Three families had made a go of it as far away as Alexandria, Egypt, and if you would believe the fairy tales, Goranis had reached Xanadu — they had supposedly been sighted peddling food in China. “They were the closest those landlocked lands had to sailors,” says Jagxhiu. “They traveled far and always brought back stories.”

Ingenuity too, adds Andrea Pieroni, an Italian ethnobotanist who has worked with them. Take halva, that paste of flour, sugar and ground sesame seeds or pistachio mixed with oil and cooked. Most often eaten after funerals in Albania these days, halva at the time was the go-to dessert.

It’s a straightforward recipe that maximizes carb, fat and protein intake and is easily preserved. Untreated, oil would drip away during cooking, drying halva into a brick. To hold the oil, extracts of Middle Eastern plants called çöğen in Turkish are added in the Levant. But the Goranis substituted the faraway plants with one from their pastures they now call chuen.

Goranis may have also been the ones to come up with ways to make boza nonalcoholic, something difficult for this fermented grain drink. The Vefa family, which runs the most famous boza shop in Istanbul, is said to have Gorani roots.

The traveling food merchants could be found all across the Ottoman Balkans, from Bosnia in the west to Constanța on the Black Sea, from Sofia down to that old levantine Salonika. Indeed, the place to go for tulumbas and kadaif in today’s Thessaloniki is the Chatzis, founded in 1908 by the progeny of a Gorani seasonal boza seller from the village Brod.

Just as Yugoslav cities had their Pelivans, almost every town in Albania had its Gegas.

In Belgrade you can go to a shop that was opened in the mid-19th century, which is run by the family of the original Gorani founder from the village Zli Potok. The family and the shop share the same name, Pelivan, which means wrestler in Turkish. The story goes that the founder won big money in a wrestling match and used the winnings to open the shop, which became so popular that “Pelivan” became synonymous with ice cream counters. Dozens of Gorani pastry shops have used the name elsewhere in former Yugoslavia. Prizren had its own Pelivan corner. Mitrovica, Niš and Subotica each still have theirs. Skopje had two.

Just as Yugoslav cities had their Pelivans, almost every town in Albania had its Gegas. Some would be sighted with trays overhead along the bazaar street in Gjirokastër. Others would establish pastry workshops in Tepelena or Durrës after peddling street food in Ioannina or Shkodër. Others still would sell halva outside factories and schools in Vlora or to football fans in Tirana. Gega turned into a vernacular last name: Qemal Bala, a Gorani who in the 1950s brought a primitive ice cream machine to the market town of Delvina on Albania’s southern tip, was known by everyone in town as Qemal Gega.

Ice cream fiefdoms

Tirana began to grow when it became the capital of newly-independent Albania early in the 20th century, and when its population boomed after World War II, the Gegas came by the dozen. Most hailed from the two main Gorani villages in Albania: Borje and Shishtavec.

A few had their own shops. One brought along years of experience from Sarajevo; another one had an ice cream maker: a vase with a mixing pad embedded inside a larger vase filled with cooling salt water. In their small rented homes, they would ferment their boza, cook the halva or caramelize the sugars in one room and sleep in the other. The next morning they would go out to sell in the streets.

If they were unmarried, one reason for their summer homecoming to Gora would be to find a bride. Another reason was to get chuen roots for their halva. But over time, after World War II, they would return to their villages less and less. Instead, for Djuren, they would often just picnic in the hills surrounding Tirana.

One afternoon per week, they would gather in each other’s homes, most often at the house of Sabir Sula, the first Gorani to open a shop in the city. He had a house with a larger yard where the families could get together — children would play, his wife Sabirica and the other women would make food for everyone, the men would chat and drink and sing.

When small businesses were nationalized in the late 1960s — erasing with a single stroke the rich tradition of bazaar craftsmen and their coffee rooms — artisans were put to work in state enterprises. The halva peddlers and boza men ended up in the centralized confectionery production and distribution lines.

Sade Danjolli rides through Tirana on his ice cream cart. Photo: Family archive of Artur Danjolli.

Some of these men helped found the main pastry factory. A few families, like the Fetishajs of Shishtavec, had representatives across the industry: one family member made puff cakes, another worked at the ice cream plant that opened in the 1960s, where ice cream was made in large vats using trucked-in ice blocks. Other Goranis worked at neighborhood sweet shops.

The rest were given bicycle carts to sell pastries and ice cream on the street.

These were the Gegas of my childhood. They had aprons and hats like nurses in a hospital. They sold all sorts of candies and cakes: burnt sugar roosters and caramel apples; caramelized popcorn balls which in an earlier time were known as Istanbul flowers; the marmalade-filled, chocolate-glazed biscuit sandwich called Moors’ heads; or the plain ingranazhe, cogwheel-shaped biscuits. In the winter, they offered meringue-topped cones, the fake ice cream. But they knew us kids were in for the real thing. Come summer, they would ride their carts down the streets shouting, “A-koo-llo-REY!”

They were given the city’s kids in small fiefs. Nurçe, the man who brought the halva-cutting machine from Romania and his experience from Sarajevo, was now selling ice cream east of town. Sade covered the center. Vajde had the area north of the train station and hated that everyone called him Cuca (“big nose”). The northwest belonged to plump Ali, an ethnic Albanian who had fled from Yugoslav Macedonia in the ’60s. The name Gega spilled over even to other ice cream men like Reshat the Gypsy and Loukas the Greek, whose territories were the industrial quarters to the extreme east and the extreme west of the city.

The inner city’s west, bordering on plump Ali’s territory, belonged to Ziqo. Every day each summer, he would fill the canisters at the warehouse near the main city square, then walk past the city’s fascist-designed main boulevard into the apartment blocks that went up in the ’60s. He would cross the Lana River by the corrugated tin shed that served as the state exhibition center and was called Albania Today.

He’d then roll his cart along Myslym Shyri Street, a one-kilometer stretch lined with trees and sidewalks and apartment buildings. The street connects the city center with the western side of the ring road, and separates the housing blocks to the south from the older houses and their meandering alleys to the north.

We knew the few state-owned shops along the street by the names of whoever worked in them.

The queues for bottled milk at Xhemile’s dairy shop would have evaporated by the time Ziqo passed. There was Tim Pallaveshi, the vegetable monger, and Lili the Limp, the grocer who ended up doing time for selling on the black market. The loitering youths would be outside cobbler Murat’s, a unit of carpet weaving women above.

There was Shati the barber and Sati the cinema manager, who would sometimes let us glance at movies from the projection room. We had even carved holes into the cinema’s exit door so we could peek at the screen without bothering to go inside, though the holes proved useless during public trials, because the whole perimeter was then studded with police. That was my neighborhood.

Ziqo would make sure to be at the elementary school near the end of the street for the 10:30 break so that he could hit the 11 o’clock break at the nearby garment factory, where his daughter worked. Then, he’d start all over.

His full name was Zeqir Kamberi. He was a father of five who lived in a small one-story shack in the city’s eastern outskirts. He was also The Gega, my childhood’s Gega, the man whose picture made the rounds on Facebook in 2019.

The life of a Gega

In the summer, Gega would run into Nasrudin, who came with his donkey into the city to sell firewood. And Nasrudin would buy two ice cream cones, one for himself and another for the donkey. Arben “Danoç” Cullhaj, who grew up in the neighborhood, told me that the kids would grin and ask: “But Nasrudin, why are you giving ice cream to the donkey?” And Nasrudin would say, “Well, he feels the heat too.” And the donkey would have a lick at the ice cream.

A-koo-llo-REY!

Kids would come running out of the houses and down the stairs of apartment buildings to throng around the cart. “Be patient,” Gega would say, “there’s enough for everyone.” They’d try to climb on the cart to peer into the canisters, but he’d chase them off. He’d roll that way on to the next block.

'Nasrudin, why are you giving ice cream to the donkey?'

The Kamberis had moved from their village to Tirana in the early 1950s: his father, an elder brother and Ziqo. A generation or two earlier, the family had peddled their goods in Romania. Family lore has it that during World War I, Ziqo’s grandfather and his brothers had been rounded up as suspected aliens and taken from there to Sevastopol in Crimea, where they worked as stevedores. The story goes that they bribed their way onto an Istanbul-bound ship, and they remained in Turkey until just before the next world conflict, when they returned to Gora.

When they came to Tirana, Ziqo did not join his father’s pastry shop initially. He served his military draft in southern Albania, which gave him his Tosk accent in Albanian, then got some odd jobs in construction. But when he got married, to a woman from the village, and the home economy was thus pressing, he got into the family business.

In the 1960s, the Kamberis rented a shop tucked between a butcher and a barber and operated a small ice cream maker. His wife and mother stayed at home, and like many Gorani women who joined their husbands in gurbet, they didn’t learn the majority language, even though their children grew up speaking mostly Albanian.

When the government nationalized small businesses in 1967, he and his brother took jobs as ice cream Gegas with the state company.

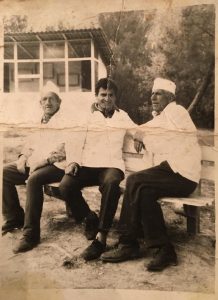

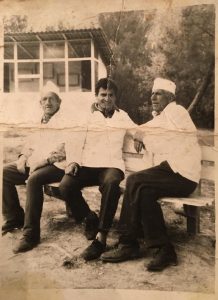

“Cuca,” Sade and Ziqo, some of Tirana’s Gegas. Photo: Family archive of Artur Danjolli.

Selling ice cream in the street is physical, but it was not a bad job for a migrant worker from the countryside during Communism. You got a small salary and extra for each sale. A crafty Gega could pull in double or triple their official salary by skimping on ice cream in every cone, making more than a police officer or engineer.

Etleva Qinami remembers Gega teaching her new words. She was barely ten years of age in the late seventies when, upon hearing his call, she rushed down the stairs only to find out she did not have the five leks it cost. “Can you give me a cone for four?” she pleaded. “I lost one lek on the road.”

“You are some smart ass, aren’t you?” he had winked, and gave her the ice cream. At home, she asked her father what Gega had meant calling her a donkey.

He’d end his day in the afternoon. Sometimes, he would give away some of the remaining ice cream or he’d send it to the sweet shops for recycling if it had not gone bad.

The loss of a tradition

Ziqo had been serving a father son pair when he was knocked down by the Polish Fiat that June of 1983.

The ambulance brought him home from the hospital later that evening. His waist and arms were bandaged. It took him some time to tell his family what had happened, his daughter Fatbardha recalled.

He had been lucky to escape with just bruises. The young man who had hit him, we had heard, had gotten the Fiat from one of the ministries near the city center after bragging to his friends in a bar he could open it with his bicycle lock key. It turned out he, or his sister, had been a high school classmate to one of Ziqo’s daughters. At one point, the boy visited Ziqo at home to apologize. He had been drunk, he said, he did not know what he was doing. Gega had forgiving words for him at the trial, because ultimately, he had recovered quickly. By August, even though still bandaged, he returned to work.

From the two men in the photo on Facebook that started this whole journey, diabetes took Hoxha in 1985 and Gega retired three years later, aged 60. The generation that slammed the ice cream man into the asphalt finally upended the system in 1990, and either got involved in making a different country, or in leaving it altogether. The children of the ice cream men were not interested in pastry jobs.

'No, you can’t sell pastries like that!'

Generational conflict disrupted even those who made an attempt to stay in the family business. Take the Fetishajs, the family that produced ice cream and cakes for the city. They had tried to kick off a candy business in the 1990s, but when Arif Fetishaj saw his son behind the counter with a flashy tight tee and dark sunglasses, he was despondent. “No,” he said, “you can’t sell pastries like that!”

Ziqo’s eldest son Gëzim, a mechanic, soon left for Greece. The family refused to join him, but Ziqo asked for an ice cream machine large enough for him to sell cones in the neighborhood. “That, and any kind of flavors you can get,” he told him.

He sold ice cream on a cart at the school near his home for six or seven years, and retired for real in 2000, when his strength was leaving him.

His son from Greece returned to Albania very rarely. A younger son, who came to be known in the neighborhood as “1997 Chimi” for his reputation during the year the country sled into anarchy (someone told me: “he hung out with the wrong crowd”), also left.

Gega passed away in 2007. He died five years before that youngest son lost his life in a freak car accident in northern Italy.

The departure

These days, a white British-registered Mercedes van connects Manchester and intermediary English cities like Woolwich and London to Shishtavec. The van brings western wares to the area and takes trinkets from home to the U.K. Sometimes it brings rounds of homemade kashkaval cheese and cured meats Gorani parents send their children in London. Sometimes it brings rounds of kashkaval and cured meats from U.K. supermarkets for parents in Albania who can’t afford their own.

When I first passed through the Albanian side of Gora more than 20 years ago, Shishtavec had only a few old people. Now many houses are renovated and each summer migrants return home with cash and energy. Many arrive on cheap flights, with the Mercedes van bringing along the luggage. But they stay long enough for the wedding and circumcision season and there are some who arrive early enough to be there for St. George’s Day, when the warm weather kicks in.

A wedding party in Shishtavec in summer 2022. The red dresses mean the woman is married, white unmarried. Photo: Altin Raxhimi.

Most Goranis now migrate west. During the homecoming season, cars with Italian license plates fill the alleys of Restelica, Gora’s largest village. Since the 1980s, they’ve been leaving for Monteroni d’Arbia, a town near Siena in Italy. Another village, Kruševo, has established a presence in Mulhouse, the French industrial town. Years after Albania opened up its borders, the Borjani began to set their eyes on Germany.

They would not go there to sell halva or roasted chickpeas.

“You know, it lets you make a living, but you can’t really make much money out of it,” says Musa Qingji, the area’s unofficial historian.

What shaped and ultimately ended the Gega profession bears the imprint of the 20th century. Empires collapsed, re-drawing borders and access to previous markets. Communism then wiped out family-run businesses. When Communism ceded, migration for jobs in the West became the norm: jobs in back-breaking construction, in car washes, in retail, in house cleaning and satellite dish distribution, in wholesale trade, in petty or serious crime. Jobs that paid better than a niche in old-fashioned halva.

There are still quite a few Gorani pastry shops in the former Yugoslavia and even in Turkey, but their numbers are thinning out. There’s just three or so of them remaining in Prizren, and gone is that town’s Pelivan. People have just figured out better ways to make a living.

This summer, I visited Gega’s house on what used to be Tirana’s southeastern edge 30 years ago but which is being rapidly taken over by new housing blocks. The door to the house, sagging with paint flaking off, opened to a narrow passageway with two rooms along the left. In the room next to the door there was a pile of bricks and rubble where an armchair had been tossed.

The other room, where two of Gega’s daughters live, was sparsely furnished. There was an open annex at the end of the passageway, which was covered with a gauze curtain. That was where they made ice cream in the 1990s. A rooster clucked and jumped in the yard. “It keeps us company,” said Fatbardha, the youngest daughter, now 58.

Seli Fetishaj, the son of Arif who made puff pastries, and nephew of Ramadan who made communist Tirana’s ice cream, has landed a job in pharmaceutical distribution. In 2007, together with his brother, he tore down the one-story shack where they lived to build the new three-story family house. The corner where their father made his cakes has disappeared. Gone were his tools and his vats.

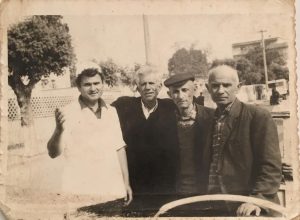

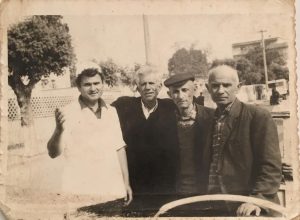

From left: Sade Danjolli, Ziqo Kamberi, Xheladin Hoxha, Nuredin Ramadani. Hoxha worked in street food, but his brother was the imam who conducted prayers at the funeral of Albania’s King Zog in Paris. Ramadani was the Gega who brought the halva-cutting machine from Romania. Photo: Family archive of Artur Danjolli.

“In his final years, Dad would wake up in the morning and go out to the yard,” Seli told me. “He’d look in disbelief at the corner where the workshop had been, as if he’d be hoping it would reappear. He’d hang in there like that, as if frozen, for hours.”

A few years ago, a tall, aging man of dark complexion was selling Istanbul flowers — remember, those are the caramelized popcorn balls — to tourists along the beach in Durrës. He told them the price for two dozen was 10,000 old leks, meaning 1,000 leks in the current denomination, roughly 10 euros.

It’s the classic tourist con in Albania. Though the government revalued the lek decades ago, it’s still common today to say 10,000 leks but mean 1,000.

The tourists didn’t know this, nor the rough conversion rate for their leks. For 10 euros worth of popcorn balls, they paid 100.

Nevruz Mehmeti, a teacher and writer from Borje, had seen the whole thing and couldn’t help exclaiming to himself aloud in našinski, “Ovja im go šibna dosta!” “Oh man, he really tricked them bad!”

The seller of Istanbul flowers raised his head. “Od kede si dečko?” he asked Nevruz. Where are you from, young man?

“Od Borje!”

“Nemoj! A me, poznavaš mene?” No way! Do you know who I am, then?

A moment or two later, they realized that their houses in the village had been right next to each other.

“A tebe ka te vikaje?” And your name, what is it? Nevruz asked.

“Jashar! Živim vo Tirana i cev život so ovja som se zimaf. Svi me poznavaje!” he said. I live in Tirana and all my life I have been doing this. Everybody knows me.

A few tourists began walking in their direction. Jashar panicked, thinking they were the ones from before, wanting their money back, Nevruz recalls.

“Zemige ovja lopke i jadige,” he told Nevruz. “Ja go izvadi račun za deneska. Selam svim vo Borje od Jashara!” Have the corn balls. I’ve made my money for the day. Tell everyone in Borje Jashar says hi.

And he left.

The old man’s full name was Jashar Berisha. He worked at a pastry shop in an industrial area west of the city in the 1970s and 1980s, making money on the side peddling halva. He was a skirt-chaser and loved taking pictures. He passed away last year. By all counts, he must have been the last surviving Gega, but it’s a long time since that name carried any currency.

Feature image: Ⓒ Michel Setboun.

The content of this article is the sole responsibility of K2.0. The views expressed in it are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of K2.0.

Curious about how our journalism is funded? Learn more here.