A Doctor in Three Wars

From Greece to Tashkent, from Skopje to Thessaloniki.

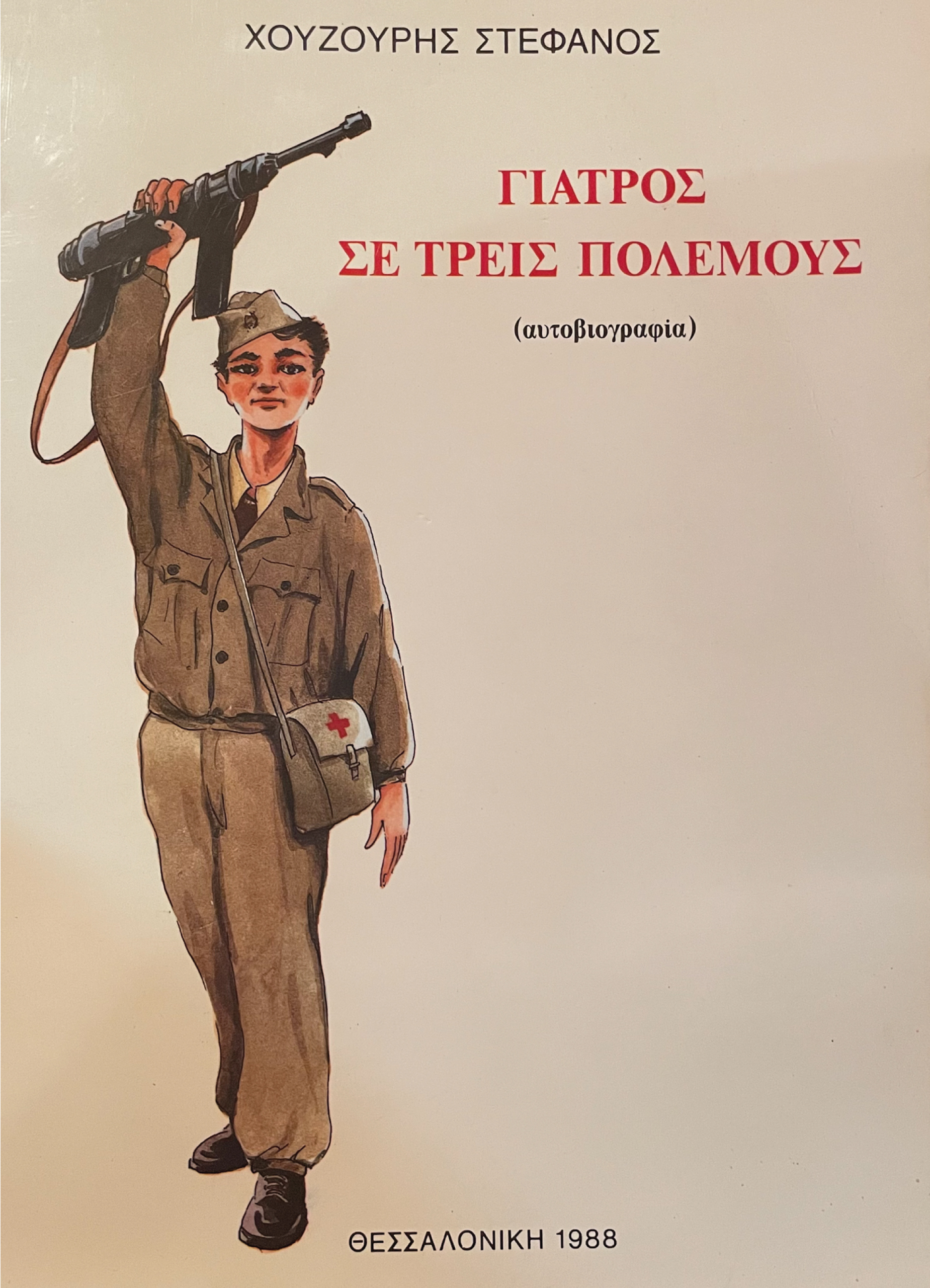

In 1988, my grandfather Stefanos Houzouris self-published an autobiography in Thessaloniki titled “A Doctor in Three Wars,” or “Giatros Se Treis Polemous” in Greek. The cover is white but for a drawing of a boyishly young soldier in khaki uniform with a red-starred partisan cap slanted on his head. A doctor’s bag with a red cross hangs across his shoulder as he proudly holds a rifle in the air. The drawing looks nothing like my grandfather, resembling instead a stock character from a 1980s socialist children’s book.

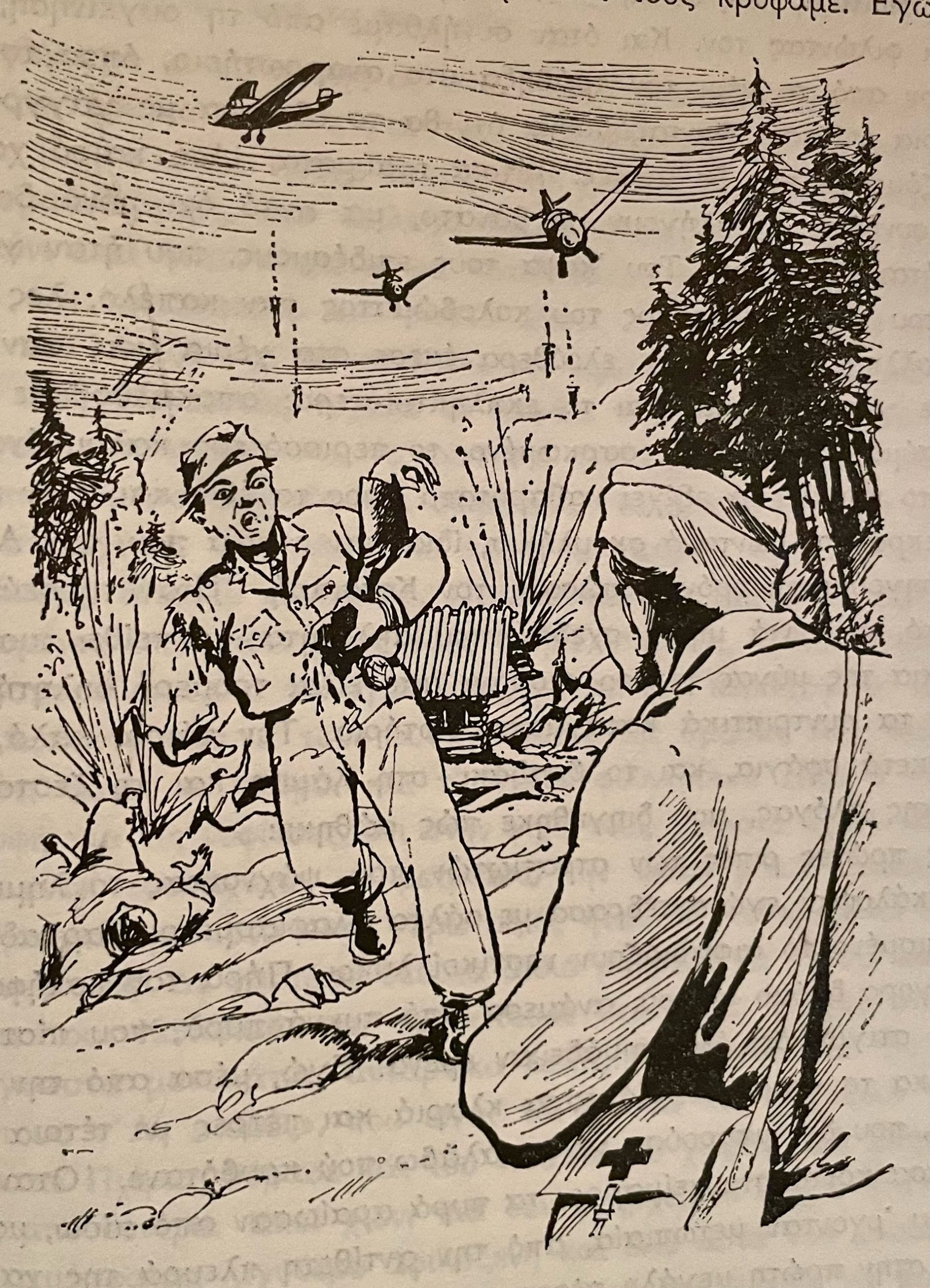

A dozen black-and-white drawings illustrate the 58 chapters in this densely printed 438-page book. As a child, I leafed through this volume hundreds of times and one drawing in particular always stuck in my mind. It depicts a soldier running toward my grandfather as enemy aircraft drop bombs in the background. The soldier is carrying his own severed bloody arm in his one remaining hand. The reason I know these pictures so well is because I could never read my grandfather’s book. Until now. Sort of.

I have been lugging this autobiography around ever since the pandemic started, set on learning Greek and finally reading it. Technically, I am half Greek: my mother was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan to my Greek communist grandparents, refugees from the civil war, who later moved to Skopje in the 1960s. I have always felt that my Greek heritage was a taboo subject in my home country due to decades of vitriolic historical and political dispute between Greece and what is now officially called North Macedonia after the signing of the 2018 Prespa Agreement, which settled the disputes at the government level. Throughout the years this political tension resonated in my family, ultimately resulting in my broken Greek.

This doesn’t mean I have no Greek at all; it was my grandfather Stefanos and my grandmother, his non-Greek second wife Marika, who taught me the language as a toddler. I spoke kitchen Greek fluently back then. The food is ready! Give me the salt. Are there any more potatoes? Who ate the ice-cream? were the types of sentences most frequently uttered in the family. I also knew a number of select insults I learned from my grandfather when he would grumble against his political adversaries. “Vlakas” (idiot) and “gaidouri” (jackass) were among his favorites. Until my grandmother Marika’s death in 2010, I could manage with this Greek, my conversations normally revolving around food anyways.

But then some humiliating experiences in Greece forced me to confront the fact that I was unable to speak the language I had been raised in. The first one was when the landlord of a vacation rental on the island Alonnisos scolded me for my poor Greek. “What is it with you?” he growled, revving the gas pedal with his bare four-toed foot up a windy road, “You can barely say a word!”

The irritation in his voice came from my claim that I was Greek, or at least half-Greek. What kind of half-Greek was I if all I could do was ask where the nearest beach was? I wanted to defend myself, but I lacked the tools. So all I did was shrug.

The second experience involves my aunt, the writer Elena Houzouri. In a strange and happy coincidence, I happen to have an aunt in Athens who is a fiction writer just like me, and who has published a novel about my grandfather Stefanos based on the very autobiography I am unable to read. Her novel bears the beautiful title “Patrida apo Vamvaki,” or “Cotton Homeland.”

Naturally, I can’t read anything that she’s written either. But she and I did spend some time together at a writers’ and translators’ retreat on the island of Paros back in 2011. It was our first meeting, a calculated attempt on the part of my mother and aunt to get me to reinvigorate my Greek and to perhaps develop ties with my relatives down south, a branch of the family I had never met before. But all that happened was I got an ear infection that made me temporarily deaf in one ear and even more impaired in trying to understand all the things my vibrantly intelligent aunt was saying.

'No one bears any grudges toward my grandfather, who apparently caused the family a lot of pain by choosing to fight for a cause. They say: He saved lives! He was exceptionally kind! He was an idealist! And he was very, very short!'

Every day my aunt and I would walk down to a dreamy village of white houses with blue window panes. At the end of a narrow cobblestone road we’d reach a cafe on a little square where under the sprawling coolness of an enormous fig tree we would enjoy “gliko tou koutaliou,” a morsel of sweet fruit preserve served with a glass of cold water.

Here I would try to converse with my chatty aunt in Greek. I remember how at one point she threw me a piercing look with her crystal-blue eyes and said, “What do you mean ‘this is good, this is bad’? Things aren’t really only good and bad, you know!”

I like to believe that I told her that I lacked the Greek skills to know any other adjectives with which I could express my opinion, that I never had the opportunity to learn more than these basic words because Greece exiled my communist grandfather and grandmother in 1949 after the Greek Civil War and proceeded to bully the inhabitants of Macedonia, the place they ended up and the nation and identity I was born to. My knowledge of the language really was that basic. This — good. That — bad.

But what kind of a writer was I, what kind of a translator was I, expressing myself like a two-year old? I felt frustrated, helpless, small. Also embarrassed. Embarrassed for not knowing one of my languages, embarrassed for not being able to defend my mother language and my heritage, embarrassed I was supposed to be an artisan of words, but had no words to spare.

I would end up saying I speak “Slavomacedonian,” which isn’t even the name of a language — it was just a way to avoid getting yelled at.

What irked me most was lacking all skills to defend my identity and provide a somewhat different perspective on the burning name issue: FYROM, Skopia, Macedonia, North Macedonia. Nearly everywhere I went in Greece, uttering the name of the county I was from was out of the question, because then I would have to explain things or risk getting yelled at. And seeing that very few people spoke English well enough to engage in verbal political combat, elaboration proved impossible.

And so, in Paros, I again kept my mouth shut and told people I was from “Skopia,” like so many times before, to avoid conflict. It made me feel treacherous and weak. Frequently someone would tell me that Macedonian was not an identity, that it was a construct, that my people stole, that they didn’t exist. I would be asked what language I spoke and I would end up saying “Slavomacedonian,” which isn’t even the name of a language — it was just a way to avoid getting yelled at.

Even still, they’d ask if that was Serbian. No, I’d reply in my broken Greek, which would get shakier by the second. Bulgarian? they’d ask. No, I’d reply. It’s a separate language. A language. But I’d get blank stares I felt were mixed with the unmistakable accusation that I was lying. If we had lied about our history — claiming as some Macedonian nationalists do that we are direct descendants of Alexander the Great and Ancient Macedonians rather than Slavs — then we surely were lying about our language too.

In the end, it boiled down to this: in Greece I was shamed for being Macedonian, so I would keep my mouth shut and sometimes even pretend I was American. In Macedonia, as a public figure who frequently criticized the right-wing government, I might get labeled a traitor if I owned up to my Greek heritage. So I kept that under the carpet.

Age could have been a factor in deciding I was tired of all this crap, but the Prespa Agreement, which paved the way for a new understanding between my two countries, helped too. It was around then that I started taking Greek classes. As a result, I can now read parts of my grandfather’s book, understanding probably a third of the words on the page, as I struggle to make sense of the hellishly complicated Greek orthography. I sit at my desk and read out loud, sounding like a third-grader, barely able to get through two paragraphs.

But once I realized I can go beyond describing things as “good” or “bad,” I wrote to my cousin Panagiotis in Thessaloniki (in Greek!) and asked him if we could meet up. I wanted to see his father Takis again, my uncle who remembers my grandfather very well. My Greek was getting better — maybe I could poke around. If I asked the right questions maybe I could get my uncle to divulge some secrets from my grandfather’s past. And so, on the first of May, I found myself on the road to Thessaloniki.

Friendships take time

I’m driving down from Skopje towards Thessaloniki with Andrej on the “Friendship Highway,” which gained this new name thanks to the Prespa Agreement. I love the name, especially since the highway used to be named after Alexander the Great. Before the agreement, it felt like everything in Macedonia was named after Alexander the Great — a historical figure I am not enamored of, much like I am not enamored of warriors with raging ambitions of grandeur. I am happy to be driving along a highway lined with bright green fields peppered with poppies, bearing a soft abstract noun for its name. The day is bright and promising.

I realize that I no longer feel the usual tension before reaching the border. I remember us — father, mother, brother, me — driving down to Thessaloniki in the early 1990s to see my grandparents who had moved back to Greece in the early 1980s. My mother would get all fidgety and nervous, a tense silence washing over us.

My brother and I would be ordered to be silent. No Macedonian word was to leave our lips, lest it annoy the policeman looking at our passports, whose brow would furrow when he’d get to my mother’s. Born in Tashkent? My mother would have to step out of the car and argue with the police officers, trying to convince them she was ethnically Greek, and not Slavic Macedonian from the north of Greece. For if she were Slavic Macedonian from Greece, she would not have been allowed back into the country.

Unlike the Greek communists who years later were allowed to return, these people were not allowed back into Greece for decades.

Few Greeks know about this ban, or that there were many Slavic Macedonians from northern Greece who were expelled along with the communists at the end of the civil war. Unlike the Greek communists who years later were allowed to return, these people were not allowed back into Greece for decades, not even to visit their relatives. Even if the unofficial ban loosened with time, the harassment continued.

As Andrej and I approach the border, I feel we live in better times, and the tension from my childhood and humiliation the border police subjected us to is no more. I tell Andrej this, that I am finally relieved of this feeling of fear and shame. He then tells me about his mother.

He says a few years back he drove his mother, Konstantina, to Greece so that she could visit a friend of hers on the Greek side of the Prespa region. Well into her 70s, the border police began to grill Konstantina. Where was she going, who was she visiting, how long would she stay, they demanded to know. After a squabble, the police officer eventually let them pass.

The harassment was because Konstantina’s Macedonian passport states the place of her birth as Konomladi, the Slavic name of a village in the Kastoria/Kostur region of Greece that Greeks call Makrochori. Konstantina was a child refugee. When she was 10, she and two of her sisters, ages 14 and 15, left their village in March 1948 along with thousands of other children who sought refuge in various orphanages in Eastern bloc countries like Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia.

Konstantina’s mother stayed behind in Greece with a toddler and baby. Konstantina and her sisters ended up in orphanages in Budapest, while the eldest sister, a partisan fighter in the civil war, escaped to Poland along with their father, who was part of the communist war effort.

Five years later, Konstantina reunited with her father in Budapest. She said she recognized him only because he had one arm. Fifteen years later, she was reunited with her mother, Alexandra, in socialist Macedonia. When they saw each other, Alexandra insisted Konstantina was not her daughter. Her daughter, she said, had fair hair. This young woman was too dark to be her child.

I wanted a diversion from these dreary histories so I remind Andrej how odd it is that his mother and my grandfather Stefanos knew each other. And that my grandfather, who was a pediatrician, was Andrej’s doctor when he was a child, and that Andrej’s sister remembers Stefanos fondly. It is a brighter story than the one about displaced children in orphanages in Europe who had to flee napalm bombs.

Instead of North Macedonia, the road sign reads “Skopia” and the letters have been defaced.

We reach the border and hand over our passports to the police officer. Before Prespa, the police would stamp a piece of paper we’d have to carry to the border every time we traveled. After Prespa, our passports are fully respected. Kalo taksidi, the police officer smiles, wishing us a nice trip.

We glide into Greece down a road lined with oleander swaying in the soft spring breeze. I am overwhelmed by feelings of hope. Only later do I notice that Greece has not changed their road signs in accordance with the Prespa Agreement. I see a barely visible sign for an exit on the highway. Instead of North Macedonia it reads “Skopia” and the letters have been defaced. I guess friendships take time.

Treason

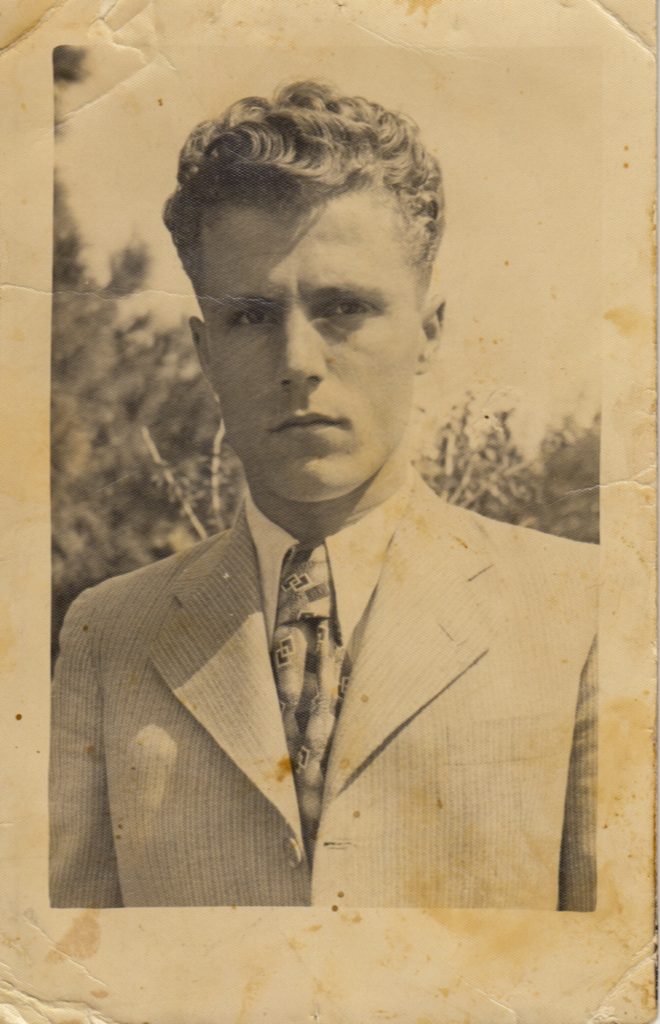

Three generations of my noisy and warm extended family greet me at Panagiotis’s home. The oldest person there is Takis, my grandfather’s nephew. The two of them were close and the resemblance is uncanny: the wavy hair, the blue eyes, the raspy voice. He is just how I remember my grandfather, who died in Thessaloniki in 1993 when my parents, brother and I were living in Tempe, Arizona.

My mother couldn’t make it to the funeral. I remember one day finding an envelope by the phone and excitedly opening it, only to find a series of pictures of my grandmother weeping over the pale, stony face of her dead husband. My grandmother Marika had sent my mother photographs of the burial, something Greeks apparently do.

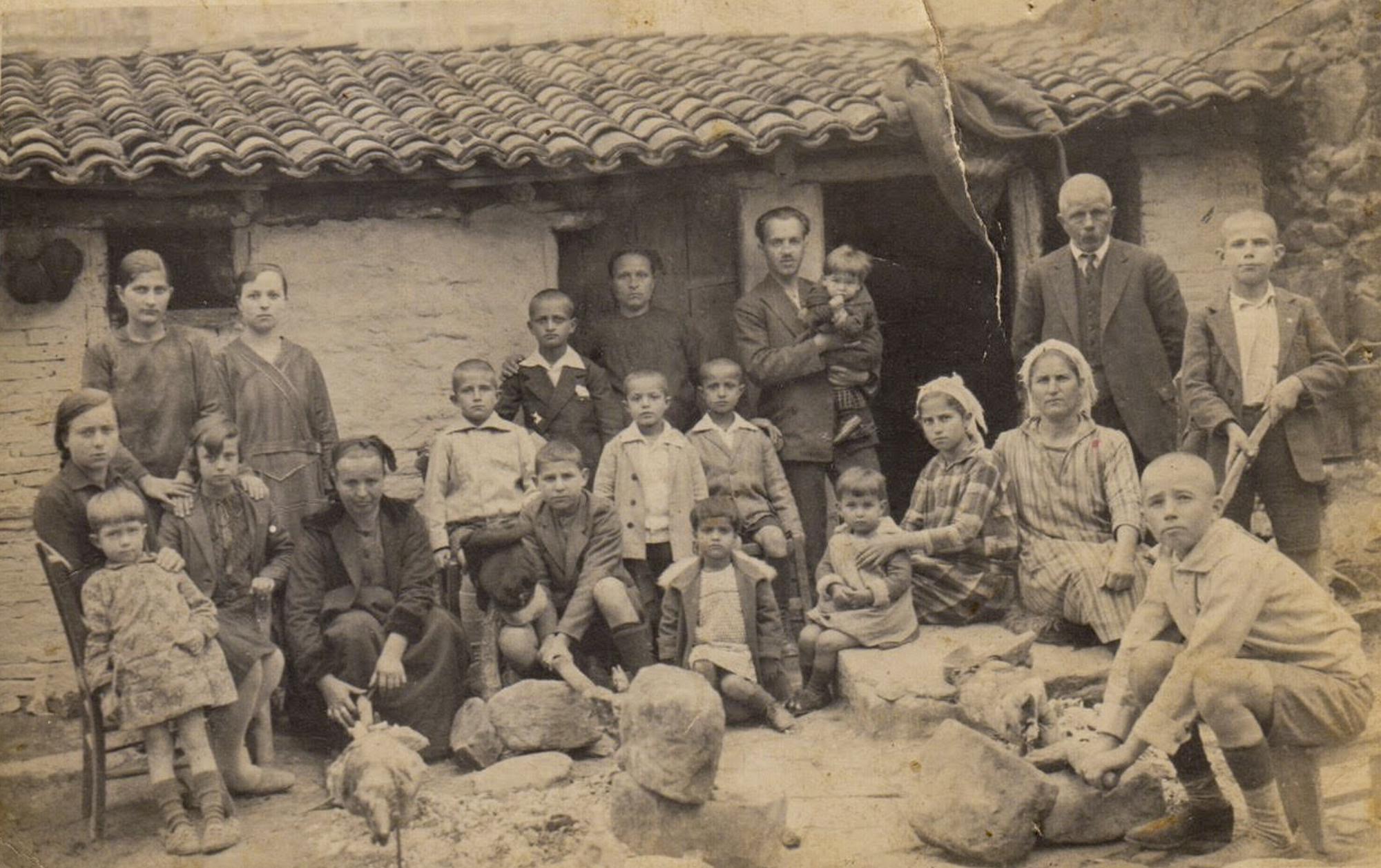

Outside Panagiotis’s house there are two tables overloaded with food. Takis is busy barbecuing the last of what looks like 10 kilos of steak and burgers. He tells me that he brought “the photograph” for me: a beautifully framed portrait of the Houzouris family stands propped up on a white plastic chair.

Once he is finished with the barbecue, Takis sits down next to me and asks what it is I wanted to know. I don’t have the Greek to tell him I want to know how they feel about our family history, that I am after impressions, not so much facts. Seeing my struggle to communicate, Panagiotis keeps gently interrupting the conversation, asking his father to describe my grandfather for me. Others join in. My grandfather was exceptional, funny, kind, idealistic, they say, but also “very short.” All true.

I hear some of the history I already know: how my grandfather was born in 1918 in the village of Kolindros in the central part of Greek Macedonia. His father Dimitris was the local teacher, and his mother was apparently the village’s rich heiress. He was the fifth of six children: three boys and three girls. He decided to go to medical school in Athens in 1935, where he turned communist during the tough years of the Metaxas dictatorship, to the great disappointment of his father.

In 1940 he was drafted to fight in the Greek-Italian War and then the Second World War. Rejecting what could have been a peaceful and prosperous life as a doctor, he joined the Democratic Army of Greece (the communists, essentially) and later fought in the Greek Civil War, after which he was expelled to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, then part of the Soviet Union, along with many other Greek and Macedonian communists. This is where he met my grandmother Chrisoula. And this is where my mother was born.

Takis tells me how his father was thrown into jail, how his grandfather Dimitris was deemed a traitor.

I ask Takis, knowing that no one else in the family was of such a determined left political orientation as him, if anyone suffered consequences because of my grandfather Stefanos. “Of course!” he cries. Takis tells me how his father was thrown into jail, how they were blacklisted by the police for decades, how his grandfather Dimitris was deemed a traitor because of his communist son Stefanos. He grips my arm and his bright blue eyes well up. “I’ll cry” he says, shedding a tear, which makes me choke up too.

The family doesn’t feel any discomfort at our display of emotions. They are chattering away and the food is disappearing fast. Here and there they chime in with a question or comment about what an exceptional impression my grandfather had left on them. No one seems to bear any grudges toward the man who apparently caused the family a lot of pain by choosing to fight for a cause. They say: He saved lives! He diagnosed my child! He was exceptionally kind! He had an incredible sense of humor! He was an idealist! And he was very, very short!

It begins to drizzle so we go mingle under the awning on the porch, where a giant chocolate soufflé, three types of ice cream and two enormous trays of chocolate and strawberry yogurt cake materialize on the table.

I find myself sitting next to my cousin Poleta’s husband, a handsome, full-lipped man with distinguished graying hair. We are having an amicable conversation about desserts, when I pop the question: How do Greeks feel about the Prespa Agreement, about the change of my country’s name to “North Macedonia”? He looks at me and tells me in a firm, yet gentle tone, that Greeks feel that this was a “prodosia.” Again, like so many times before, I’m missing the key word. “What is prodosia?” I call out to my bright and beautiful 20-something year-old nephews who have provided English translations throughout the day. “Treason!” they chirp.

Dusk falls and the family begins singing. I can’t really participate because I don’t know any of the Greek songs. Perhaps it’s time to go, I think to myself. I step inside the house to visit the restroom and I close the large balcony doors behind me. Alone in the large, dark salon, the voices sound distant and my senses sharpen. This part of the house belongs to my cousin’s in-laws, who are now in their 80s.

I close my eyes and inhale deep through my nose, having sensed the scent of my grandparents’ apartment. I wonder what the source of this distinct smell is. I spy a collection of old-style irons in different sizes atop a hearth and a dozen shepherd canes in a bucket; more than thirty decorative plates hang on the walls above a lavish assortment of evil eye talismans. Hundreds of miniature porcelain and glass trinkets crowd the shelves of the vintage cabinets made of dark, rich wood.

I tiptoe into the bedroom and find the walls covered with family pictures of weddings and baptisms. In a corner by the bed, a few icons and crosses decorate the wall. Candles sitting on pouches of pink tulle lay forgotten in another corner of the room, atop an old straw chair. And I slowly realize that the faint scent of so many of the Greek houses I’ve been to is that of a church.

A mother’s clean house

A charming clutter of trinkets, souvenirs and strange objects also filled my grandmother Marika’s homes. I would pull open a drawer to find a pair of knee-high stockings next to a batch of embroidered decorative linens and a candy box full of buttons or stale almond candy.

I have, or had, two grandmothers. There was my beloved Marika, my grandfather’s second wife, who never had any children of her own. And there was Chrisoula Pouliou, my biological grandmother, who died almost a decade before I was born and whose difficult life was, I believe, devoid of clutter and small pleasures.

Marika was Slavic Macedonian from the town of Giannitsa in northern Greece. Her loving husband Andon had died a few years before she met my widowed grandfather in Skopje in the late 1970s.

The story of my grandmother Chrisoula, who was only 48 when she died in 1973, is tragically conditioned by her womanhood. Born in 1924 in the Thessalian village of Mavreli, she was one of six children. Like my grandfather, she also came from an established family: her grandfather was a mayor, her father a doctor, and her mother, whom people called “giatrina” (the doctor’s wife) established the first mill in the region and managed to save families from starvation during the Second World War.

The eldest of my grandmother’s brothers, Giorgios, went to study law in Athens in the late 1930s and turned communist. His two younger brothers Sterios and Vasilis followed suit. After fighting in World War Two, they joined the communists in the Greek Civil War. What transpired was a tragedy: Georgios’s unit was ambushed and he committed suicide by throwing himself on a grenade.

The civil war was coming to a bloody end for the communists, and my grandmother and her mother were instructed to run to the mountains to join the partisans, where the two surviving brothers were. In the attempt to salvage anything from their home, the two women hid some of their household goods with neighbors. But the next day, the royalists scared the villagers into relinquishing anything they had from the Poulios household. They stacked it all in the middle of the village and burned it. Then they set fire to their house.

Until the end of the civil war, my grandmother and her mother cared for partisans hiding in the woods and mountains. My grandmother was a nurse, my great-grandmother a cook. After she was exiled, Chrisoula continued working as a nurse and midwife in a Greek hospital in Tashkent. The picture I have of her, smiling in her white uniform with two other midwives and the gynecologist is unusually cheerful; normally, the pictures of the women after the war are bleak, showing them black-clad, exhausted, starved, bereaved.

Chrisoula married my grandfather Stefanos in 1952 in Tashkent. I am not sure whether this was a love marriage, or simply a marriage of convenience between two refugees surviving in a Greek ghetto in the Soviet Union. My grandmother continued to provide care and life as was expected of women: she gave birth to two daughters, my mother Eleni and my aunt Alexandra, and maintained a perfect state of cleanliness, something not unusual in Greek households.

Ironically, it was this religion of cleanliness that partially accounts for her early passing. It seems that Chrisoula held a grudge toward her brother Sterios’s wife Anna. Anna was Russian, and to the refugee Greeks, she seemed impertinent in her progressiveness. She dressed differently, and, most egregiously, didn’t maintain a sparklingly clean house. This led to my grandmother and her mother calling her “Anna the stink.” Which, in turn, led to a falling out with Sterios.

My grandparents, with my mother and aunt in tow, left Tashkent for Skopje in 1967 in order to be closer to Greece. They were waiting for the Greek military junta to fall, longing to go back and be reunited with their families. My grandmother left Uzbekistan without saying goodbye to her brother.

Three years later she found out he was dying of cancer, so she made the long journey back to Tashkent, where she cared for him for three months until his death. When she returned to Skopje, she was unrecognizable. The ordeal of caring for her brother, and I assume, the years of life wasted on a silly argument, had taken their toll. She was soon diagnosed with breast cancer and died a slow and painful death in Skopje. She is buried in a city that was unknown to her, in a land whose language she never learned. She is alone. Every now and then, my mother and father visit her lonely grave. And they clean it.

Naming, re-naming and name-calling

When the pandemic hit, Andrej and I moved to the house in the mountains my grandfather built in the early 1970s with a comrade from the civil war. My grandfather and his friend Petar Sarakinov were both from northern Greece, but my grandfather was Greek Macedonian and Petar was Slavic Macedonian. The house is split vertically in half, so the two families virtually lived together.

Spending every summer there, I was convinced that everyone spoke both Greek and Macedonian. Two houses down was Dimitar Vrandeliev’s house, another communist fighter who ended up in Tashkent before moving to socialist Macedonia. Another two houses down, there was a communist Macedonian-Greek couple who spoke both languages to their children, throwing in a bit of Russian here and there.

Then one summer, when I was about eight years old, I had a spat with one of the neighboring girls, Viki. She turned to Beti, from the Vrandeliev family, and snickered “you are playing with the children of Greeks.” This was the first time I became aware of any kind of difference between us. That same summer, the boys smeared cow dung on the doorknob of the only Albanian-owned house in the neighborhood.

I started registering the casual slurs I was hearing. Some Macedonians used “Egeec” or “Egejka” as a pejorative for Greeks and Macedonians from Greece. Then there was the inevitable “Shiptar” or “Shiptarka” for Albanians. Nowadays I recognize an even wider repertoire of slurs my Macedonian neighbors here use when they complain that Albanian families have bought some of the houses in the area. They use words that translate into “Indians,” “Shoshoni,” “tribe,” and most frequently, just “they.”

I spent most of my summers here with my younger cousin who now lives in Phoenix, Arizona. At birth, he received the Slavic name Borjan. When he was six, he and my aunt moved to Thessaloniki, to be close to grandfather Stefanos, who had repatriated to Greece in the 1980s and opened a practice there. My grandfather died a few months after my cousin and aunt arrived.

To gain acceptance and to obscure his other identity, my aunt changed my cousin’s name to Ioannis. But that really didn’t help. In school he was bullied, especially by his teachers, and was called “Turkoslavos.” My cousin tells me the Albanian kids were bullied by the teachers too. Once, he told me, a teacher grabbed Eno, an Albanian classmate, by the hair and made him stand in front of the class, where he beat him and cursed him, saying “gamo tin Alvania sou,” or “fuck your Albania.” At 16, my cousin moved to the United States. There he changed his name again. Now he is John.

When the Prespa Agreement was signed I cried tears of relief. It seemed like a first step in bringing the two sides of my family, of myself, into harmony.

My Macedonia is a small and impoverished country with a deep inferiority complex and a grave problem with toxic nationalism. But all of our problems have been made worse by the bullying of our stronger neighbor to the south. Despite the fact that the Prespa Agreement was the result of this bullying, when it was signed in June 2018 I cried tears of relief. It seemed like a first step in bringing the two sides of my family, of myself, into harmony.

But I now see the repercussions are serious, as Bulgaria is currently following Greece’s precedent in blocking our path to the EU and trying to impose its own historical, linguistic and ideological views onto us. This has resulted in a surge of Macedonian nationalism and, tragically, greater ethnic tensions between North Macedonia’s ethnic Macedonians and the large Albanian minority.

Nevertheless, I still feel the Prespa Agreement was the only way to move forward. I can’t help thinking about my grandparents, their lives lived on both sides of the border. Surely, I think, they would be relieved to see the two peoples getting along again, knowing how much they detested nationalists and what sacrifices both had made for the sake of their ideals.

Living in the house my grandparents built, their presence still lingers in faint scents in various corners. And I’m still lugging around my grandfather’s heavy book, reading small snippets here and there. As a writer and translator and literature professor, I like especially the last sentences of the book — one of the only sections I’ve worked out the exact meaning — where my grandfather’s voice still rings alive and true:

“Read, read, read: this is exactly what our ill-intentioned foes don’t want us to do. By reading you will be able to easily tell the difference between the sweet fragrance and the rot of stench, between the living and the lifeless beings; you will recognize the thieves and the liars, you will separate the light from the darkness and the truth from the disguised lies.”

Feature image: Author’s family archive.

![]()

![]()

This article has been produced with the financial support of the “Balkan Trust for Democracy,” a project of the German Marshall Fund of the United States and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Balkan Trust for Democracy, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, or its partners.

Why do I see this disclaimer?

- This story was originally written in English.

Having graduated from the Department of the English Language at the Faculty of Philology "Blaze Koneski" shortly after Rumena, and having had the pleasure and honour of being taught by Professor Eleni Buzarosvka during my undergraduate studies, I had oftentimes wondered about the life story of the only person I personally knew with a very obvious Greek name (Eleni) in my country, now called North Macedonia. I found a moving and satisfying clarification in Rumena's sober, yet intimate and, at times, deeply emotional account of her search for her identity, like pieces of a puzzle, across two neighbouring countries and moving perosnal histories of many family members. Furthermore, as a descendant of a family from Voden/Edessa in Greek Macedonia, on my father's side of the family, through a great grandfather who escaped North as British soldiers burnt down his village in Wold War One, I had always felt a certain uneasiness around aunts and uncles in the Voden/Edessa region who spoke a Slavic language and their children, my cousins who didn't, and can sense in Rumena's story the painful sensitivity of issues that cannot be explored deeper with family members, what for lack of a common language, what for lack of a common willingness, and worst, because of fear of a conflict or repercussions. Meanwhile, I find solace in the connections that thrive, despite so many nationalistic obstacles. Going to Greek Macedonia and further south in Greece I have made many friends and managed to maintain a weak, but ongoing communication with my family in Greece. Throughout it all, I have healthily questioned my identity as a Macedonian from North Macedonia, not because I had doubts of it, but because everyone of my neighbours, especially Greece and Bulgaria, question it continually. The EU is proving a disappointment as an enabler of harrassment of nations, conditioning the entry into an economic union with subjugation of aspiring members by current members, encouraging meddling into national identities, and fuleing nationalistic desiers and aspirations. I too thought people would put behind their troubled and tortured past after the Prespa Agreement but it seems it has become an excuse for further destabilising in the region with a sort of a domino effect. Why can't more people be interested in reaching out to others like Rumena, instead of labeling and hating them?

I wish I could write about the tens of thousands of Greeks who were forced to abandon their homes in Bitola, Strumica, Gevgelija, Ohrid, Krusevo and Morihovo in what is now the "Republic of North Macedonia". Rumena Buzarovska cannot escape the communist propaganda that gave birth to a nation that was never really meant to exist. I wish I could write about the waiter in Bitola who still speaks Greek with the clients in the restaurant he works in, but tells his boss he learned the language at some language school. I wish I could write about the Serbian professor of physics in Skopje who says she is Macedonian because otherwise she will lose her job. I wish I could write about the ethnic Greek, non-communist grandfather of my friend who was abducted as a child by the communists and was sent alone, without his parents, to Tashkent, only to find his way back to Greece after a decades long struggle of his family in Greece. I wish I could write about the ethnic Bulgarians in the "RNM" who form long lines at the Bulgarian Embassy in Skopje in order to secure a Bulgarian passport, ostensibly because it makes traveling within the EU easier. I wish I could write about the Greek communists who did not fight for ideals but they fought in order to sever Greece and establish a communist government in Greek Macedonia which would later unite with Yugoslavia into some sort of Stalinist paradise (that was before the Stalin-Tito breakup). I wish I could write about my friends from a village near Florina who speak Slavic, but refuse to identify themselves as anything but Greek, but not because of Greek repression because they had lived all their lives in Germany. I wish I could write about the native Greek Macedonians who have always lived in geographical Macedonia, for at least 1,300 years before the first Slav set foot, a native Greek population with its own dialect, customs and local history, including five revolutions against the Ottoman rule and a long and bitter Macedonian Struggle against Bulgaria of San Stefano as well as the declaration of the first modern state entity to bear the name Macedonia in 1878, 14 years before Josip Broz Tito, the founder of the fake Macedonian nation was born. I wish I could write about how no Slav in geographical Macedonia had any other identity but Bulgarian, the only Slavs defining themselves as "Macedonian" being the communists. This is why the USA forbade the migration of people defining themselves as "Macedonians" in the 1950s and 1960s: because it considered them to be not of a separate ethnicity, but Bulgarians communists. I wish I could write about the leveling of the right bank of Vardar River in Skopje after the 1963 earthquake, which was not an act of nature but a deliberate crime against humanity by Tito who destroyed what was a city with an 80% Albanian ethnic majority in order to replace it with fake Macedonians. The earthquake was no doubt powerful, but if you look on the other side of the river you will find the Albanian neighborhood of Cajr with its commercial buildings from the 1920s and 1930s still standing intact. Maybe I will write about all that. I owe it to my homeland and my ancestors. I need to defend the truth.

Ce témoignage est magnifique et triste à la fois. Ce fut une époque tragique dont s'est inspiré l'écrivain macédonien Tasko Georgievski : toute son œuvre, une vingtaine de livres, est consacrée au destin des Macédoniens expulsés du nord de la Grèce pendant la Guerre civile de 1945-1948. Deux de ses livres sont traduits en français: Le cheval rouge (Ed. Cambourakis) et La graine noire. (réédition en fév. 2024 chez le même éditeur). C’est en 1946, pendant la guerre civile qui ravage la Grèce, que sa famille quitte le village natal. Âgé de onze ans, l’enfant emporte dans ses bagages tout le drame de ses concitoyens. Félicitation à Rumena Buzarovska d'avoir levé le voile sur ses événements tragiques et leurs conséquences.