In the summer of 2021, while natural disturbances like extreme rainfall, hail and floods were ravaging Northern Croatia, the south of the country struggled with fires that left in their wake distressing scenes of charred trees, thinned out undergrowth and desolate landscape. Croatia had already lost 62,008 hectares of forests in similar wildfires between 2017 and 2019.

Yet the biggest threat to Croatian forests are not wildfires, but rather excessive profit-oriented deforestation.

“At least 1,000 hectares of forest have been cut down over the last ten years,” Vesna Grgić said over the phone. She has been fighting for forest conservation for years.

Short-haired, with a hoarse voice and decisive gestures, last year Grgić became the face of the fight against deforestation in Croatia. The military veteran leads Zeleni Odred (The Green Squadron), a forum of the Veterans’ Association ViDrA – Veterani i društvena akcija (Otter – Veterans and Social Action), which was founded in 2017 on the initiative of antifascist-oriented veterans of the Croatian War for Independence.

Zeleni Odred became involved in conservation activism by chance; its members had begun spotting an increasingly large number of naked slopes and wastelands on their trips into forests. In time, they connected with experts and other distressed citizens who started to send them photos of devastated local woodlands.

Vesna Grgić and other activists from Zeleni Odred strike back against illegal logging and the destruction of the natural environment. Photo: Zeleni Odred.

“We can’t say that a specific part of Croatia has it the worst… there’s devastation everywhere,” a bitter Grgić said.

State-sponsored devastation

According to Zeleni Odred, the main culprit for the destruction of forests in Croatia is Hrvatske Šume (Croatian Forests), a public company dealing with forest management. State-owned forests make up the bulk of woodlands in Croatia; out of 2,759,039 hectares of forested area, 2,097,318 is state-owned. Grgić and Zeleni Odred claim that Hrvatske Šume does not manage forests in line with public interests. To back up their claims, they have been collecting evidence for years.

Back in 2018 Zeleni Odred filed a 700-page-long report on corruption to the State’s Attorney Office and the Anti-Corruption Office. They believe they have enough evidence to prove that the reason for excessive deforestation is timber resale, which favors private entrepreneurs. The association also suspects that some high-ranking officials are engaged in corrupt acts.

“The price of timber in Croatia is extremely low due to state incentives and this goes in favor of the wood processing industry. What we have at hand is a feed-in price aimed at wood industry development,” Grgić explained, adding that timber is sold for next to nothing.

Earlier this year, Zeleni Odred sent documentation to the European Commission identifying a misuse of European funds set aside for forest restoration as well as some inconsistencies in the protection of forests.

"Forests can be exploited, but it is to be carried out sustainably so as to protect the habitat and biodiversity."

MEP Thomas Waitz, Austrian Green Party

The European Union — at least in principle — cannot meddle in member states’ internal affairs, but 36.67% of Croatia’s land area and 16.26% of its territorial and internal waters are covered by the Natura 2000 network. Consisting of “areas important for the preservation of endangered species and habitat types in the European Union,” the aim of this network is to “maintain or restore to a favorable condition more than 1,000 endangered or rare species as well as around 230 natural or semi-natural habitats.”

As of 2015, Croatia was the EU country with the second highest percentage of territory covered by Natura 2000.

The areas belonging to Natura 2000 are not completely excluded from economic exploitation. However, logging comes with the obligation to do reforesting.

“Forests can be exploited, but it is to be carried out sustainably so as to protect the habitat and biodiversity,” said MEP Thomas Waitz from the Austrian Green Party.

People take photos of places struck by illegal logging and regularly send them to Zeleni Odred. Photo: Zeleni Odred.

In late July, Waitz made a formal visit to Croatia on behalf of the European Commission. He visited and documented the degraded woodlands in order to present a report.

“Violations against the Natura 2000 network are taking place across Europe; this is no ‘privilege’ of Croatia or the region,” he said, adding that the scope of devastation is extremely large in countries such as Croatia, Romania, Slovakia and Poland.

“It seems that the connecting thread between Croatia and Romania is that state-owned forestry companies are implicated in an excessive exploitation of forests,” noted Waitz, who is a forester by profession.

A desolate region

Zeleni Odred’s actions connect people from across the region. Among others, they served as an inspiration to Dragana Arsić, a former bank clerk and nature lover who lives in Serbia.

Arsić first took up activism by joining the movement “Odbranimo reke Stare Planine” (Let’s Defend the Rivers of Stara Planina), which advocates a ban on mini hydroelectric dams in the Stara Planina mountain area. Afterwards, while she was hiking near a local climbing hut, she saw clearings dotting the area once covered with trees.

“I realized that a forest was disappearing under my nose while I was fighting for rivers 600 kilometers away,” Arsić said.

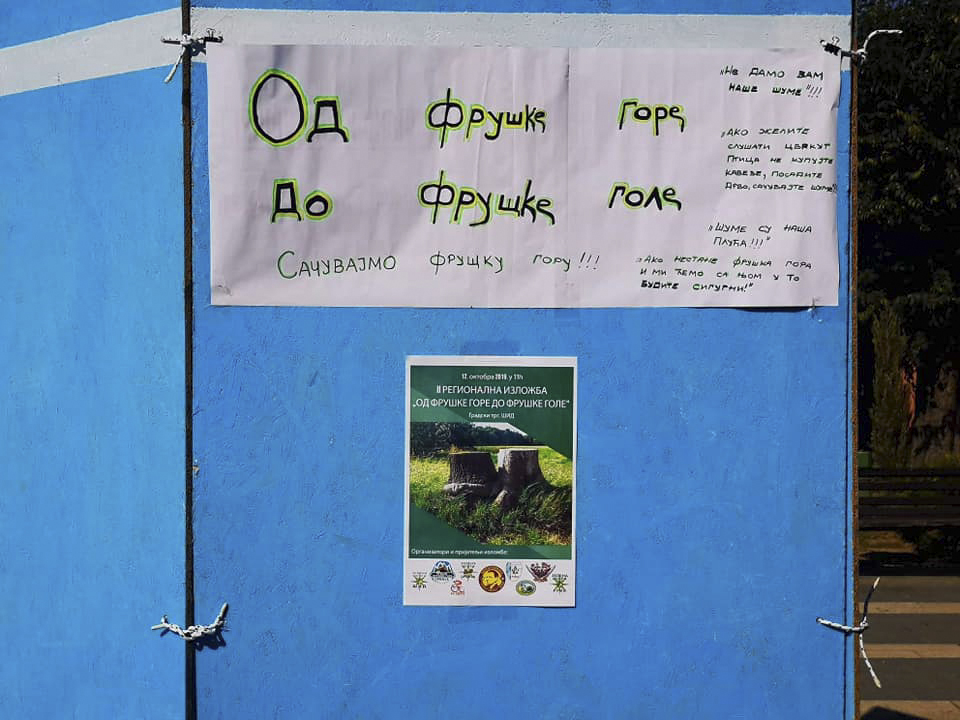

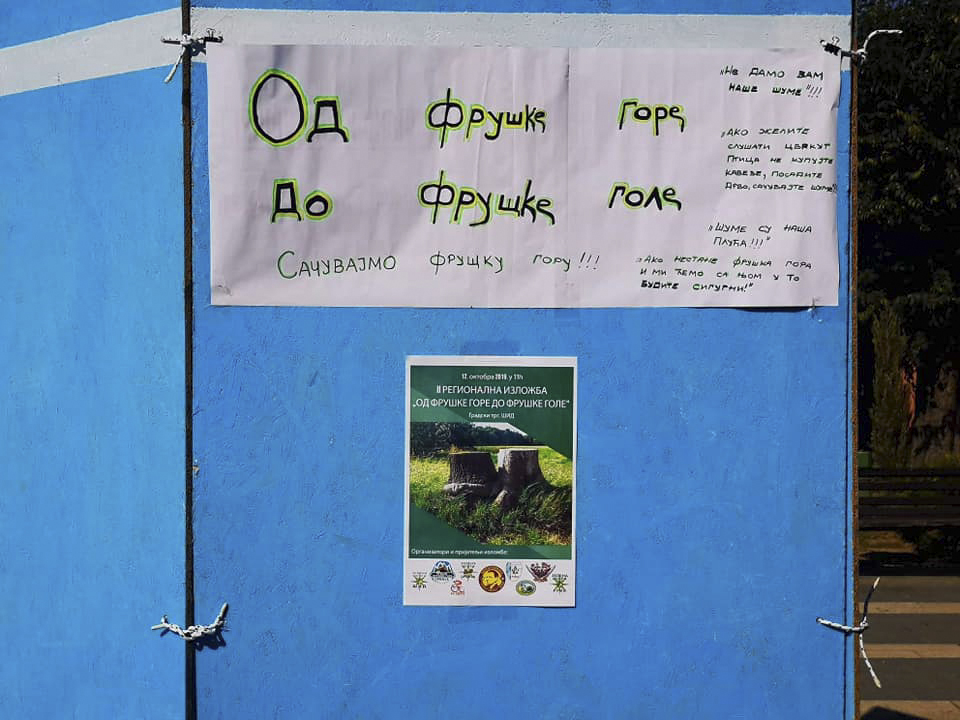

In late 2018, she created “Odbranimo šume Fruške gore” (Let’s Defend the Forests of Fruška Gora), a Facebook group and civic initiative that decided to put up a fight against excessive deforestation.

There are no borders for regional ecologists, so Zeleni Odred joined the protests in Fruška Gora. Photo: Zeleni Odred.

Though Fruška Gora is the oldest national park in Serbia, profit-driven logging is allowed there.

“At the start we realized that such a management model wasn’t sustainable. Forests are managed so as to reap commercial profit, which is then used to fund the company itself [the Fruška Gora National Park],” Arsić explained. She added that the National Park, as a public company employing 135 people, is mostly funded by logging operations — these make up more than 60% of the company budget.

“Forests are managed as if they were private property and the management itself is dominated by its economic function, while the environmental one is completely brushed aside,” Arsić insisted.

She also said that she and other activists face frequent backlash due to their public engagement as well as because they regularly inform the relevant inspectors about illegal and excessive deforestation.

“We’re considered fake environmentalists and mercenaries paid by foreign actors. Since the beginning, another leitmotif has been that we challenge forestry as a profession by criticising how forests are currently managed, while supposedly not being competent to properly take care of forests ourselves,” Arsić noted.

Reforestation totals fell from 992 hectares in 2015 to 614 hectares in 2019.

On the other hand, the 2010-2020 State Audit Report published in January 2021 shows that the current state of affairs is concerning.

Vojvodina — where the Fruška Gora National Park is located — is one of the least wooded areas in Serbia and Europe, with less than 7% of the area covered in forests. The State Audit points out that woodlands represent around 30% of Serbia’s total land area, while optimal tree cover would be 41.4%, according to the objectives set out in the 2010–2020 Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia. By contrast, the EU average is 39%.

The State Audit also established that reforestation efforts saw a decline between 2015 and 2019. Reforestation totals fell from 992 hectares in 2015 to 614 hectares in 2019.

According to the Serbian Statistical Office, woodlands cover an area of 2,237,511 hectares. 57% of this is private property, while 43% is state-owned.

A large number of people from across the region have joined the activists protesting in defence of Fruška Gora. Photo: Odbranimo šume Fruške gore.

“Private forests should be managed sustainably too, but that’s left to the discretion of owners and it’s fairly disorganized,” said Goran Sekulić from WWF Adria (World Wide Fund for Nature Adria), the regional branch of the World Wide Fund for Nature.

“This should be kept in check by inspections, but sometimes it’s done a bit non-systematically. Plots of land are small in the Balkans; one plot often has dozens of owners, and usually it turns out that no one knows who owns what,” Sekulić said.

Administrative jungle and illegal logging

In Bosnia and Herzegovina — where the total wooded area amounts to an enviable 53% of the country’s territory — unsystematic forest management is present even at the national level. The three units constituting the state (the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Brčko District, and Republika Srpska) manage forests via their respective ministries. In the Federation, some forest management competencies have been passed down to the cantonal level ministries responsible for forestry.

“Generally speaking, forests are the type of resources for which it is logical to manage them in an integral manner,” Sekulić said.

“Any further administrative fragmentation would only reduce the efficacy and allow room for corruption and some particular interests to be furthered. If you give some competencies down to the cantonal level, a forestry strategy won’t work as a whole,” he concluded.

The lack of an adequate forestry strategy is fertile soil for illegal logging.

In its 2000 forest status overview for BiH, the UN states that “approximately 1.2 million cubic metres of illegal or suspicious timber” is annually imported from Bosnia into the EU. More recent data is not available.

The Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Water Management, and Forestry reported that it “does not possess any information on the total amount of illegal timber across cantons.” However, its recent report on forest management shows that the eight cantons that have provided the relevant data recorded 2,995 misdemeanor and criminal charges in relation to timber theft in 2019 alone.

In Kosovo, where 45% of the territory is covered in woodland, illegal logging is one of the biggest issues plaguing the protection of forest resources.

In late 2019, Bosnia made it possible to obtain a certificate issued by the Forest Stewardship Council, an international organization dealing with responsible forest management. The FSC certificate is primarily intended for consumers and it guarantees that FSC-certified products are not made from illegal timber, but are sourced from forests that are managed transparently and in line with key international regulations and local legislation.

“It’s a good mechanism in theory, but it doesn’t mean much per se as long as it isn’t accepted by everyone in the industry,” Sekulić warned.

In Kosovo, where 45% of the territory is covered in woodland, illegal logging is one of the biggest issues plaguing the protection of forest resources.

“Our forests annually yield around 1.6 million cubic meters of timber, while Kosovars’ needs accrue to around 1 million cubic meters,” explained Adrian Emini from KOSID, the Kosovo Civil Society Consortium for Sustainable Development. “Prompted by adverse social and economic circumstances, many families see illegal logging activities and timber sale as their only source of income.”

According to a recent KOSID study, wildfires, poaching, and illegal logging are the main threats to Kosovo’s forest resources, and especially vulnerable are the Sharr Mountain and Bjeshkët e Nemuna National Parks.

“The government is unable to provide a sufficient number of park rangers, among other reasons, because of a lack of funds,” Emini noted, adding that forest protection officers have found that illegal logging operations in Kosovo are led by organized criminal groups. He also pointed out that 500 lawsuits have been filed against illegal loggers in the last decade.

The report Zeleni Odred filed to the European Commission and the visit of MEP Waitz are only the first steps in the defence of forests. Waitz explained that in similar cases, following an analysis of the documentation, the first thing is to arrive at a consensus and compromise with the state in order to stop the deforestation process.

“But if the state doesn’t respect the rules and/or if forest devastation presses on, some sort of sanctions can be imposed,” Waitz noted.

Croatia is not the only EU country to be rapidly losing its forest cover. The last decade has seen such a sharp increase in forest devastation that woodlands now absorb less and less carbon dioxide, which has triggered a number of warnings.

The reduction of forest coverage could, apart from having catastrophic consequences for biodiversity, hamper the implementation of the European Green Deal, in accordance with which an emissions limitation would be able to bring global warming down to 1.5°C.

On July 14 the European Commission presented a package of 13 legislative proposals called “Fit for 55,” which would be crucial for achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. One of the bills pertains to reforestation, aiming for three billion trees to be planted throughout the EU by 2030.

The Balkan countries do not have any comprehensive plans related to forest protection. However, there are some individual initiatives, most of them coming from the civil sector and people like Vesna Grgić, Dragana Arsić, or other activists. One such initiative has been set up by the Novi Sad-based music festival Exit with the goal of planting one billion trees by 2050. Nevertheless, it is unclear who would organize such actions and who would monitor them.

Feature image: Courtesy of Zeleni Odred.