At the awards ceremony of the 2006 Berlin International Film Festival, English actor Charlotte Rampling tried to pronounce the title of Jasmila Žbanić’s winning entry “Grbavica.” While there had been previous competing titles, this marked the moment when the Berlinale opened its doors wide to post-Yugoslav cinematography, as well as to all the gaping wounds for which only the arts remain to provide stitches.

Managing to mispronounce it as “Grabavička,” Rampling was nevertheless able to feel the weight of this word, if only for a brief moment, as this toponym entails the stories of 22,000 women raped during the Bosnian War. This horror is what Žbanić’s movie is about.

“War criminals still roam freely in the streets of Europe,” Žbanić said in her award acceptance speech. “They have not been arrested for having organized the campaign of rape that destroyed the lives of 22,000 women in Bosnia and Herzegovina… I hope this will change, and I wish the Golden Bear won’t end up being disappointed when he arrives in my country.”

Thirteen years later, all sections of the 69th Berlin International Film Festival — which is taking place between February 7 and 17 — including the Competition section, will feature at least one co-production between the post-Yugoslav countries.

Teona Mitevska, director of “God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunya.” Photo: Beata Siewicz.

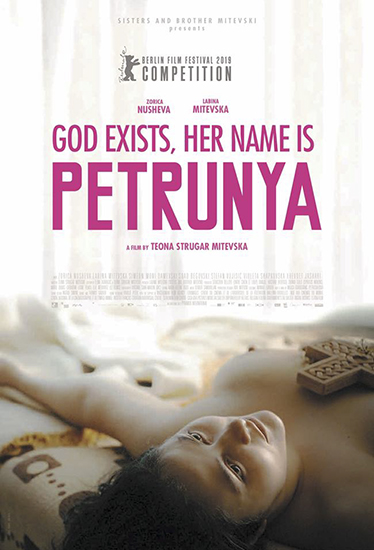

Among the movies scheduled to be screened this year are the Macedonian production “God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunya,” Teona Strugar Mitevska’s entry in the main competition for the Golden Bear; another is Miroslav Terzić’s “Stitches,” a Serbian picture set to premiere as a part of the Panorama section; finally, Kosovo is represented by the short film “In Between,” which is made by filmmaker Samir Karahoda.

A dream come true

Karahoda’s “In Between” (or, “Në Mes” in Albanian) will be the first motion picture to introduce Berliner filmgoers to film production from Kosovo. Apart from it having been selected for the official Festival program, the Kosovar director considers the fact that this work has been created by a domestic team funded by local organizations to be a great success.

“The movie shows that people in our country have got the capacity to make true cinematographic works, and what better place to promote them than at the Berlinale,” Karahoda said.

“In Between” theatrical release poster.

Revolving around family and coexistence, love and respect among family members, this short drama film is dedicated to all parents living in hope that their sons will someday return to their homeland — thereby also touching upon migration as an omnipresent issue.

The title “In Between” ultimately reflects the circumstances in the present-day Balkans, where once lively villages have slowly but surely been turning into ghost towns, due to corruption and policies inadequate to prevent such a trend. The work itself comprises awe-inspiring images of rural areas in Kosovo with a hint of poetic sensibility, interspersed with the portraits of families. These are painted by a narrative voice which frames the still void looming over the abandoned settlements.

Samir Karahoda, the film director who made the first Kosovar motion picture ever to be screened at the Berlin International Film Festival. Photo: Elmedina Arapi.

Karahoda, also a member of the DokuFest team, held that the Berlin International Film Festival is one of those institutions that have encouraged regional cooperation in terms of cinematography. However, he argued that, as a general rule, the other Balkan countries tend not to join forces with Kosovo in this respect.

“Kosovar cinematographers have worked side by side only with their colleagues from Macedonia, and there’s an agreement signed with Montenegro, too,” Karahoda said, before arguing that the main reason for this lies in the political climate in the region. “As long as we keep running into problems with freedom of movement, and as long as we keep hearing hate speech coming from politicians’ mouths, especially the Serbian ones, the chances for us to cooperate are going to be rather slim.”

Sarajevan screenwriter Elma Tataragić has penned two films scheduled to be shown at the 69th edition of the Berlinale. Photo: Eugen Berger.

Nonetheless, two motion pictures challenge the argument of the Kosovar filmmaker. One of them made in Macedonia, the other in Serbia, and both written by Elma Tataragić from Sarajevo, these works of art show that film directors from the region are indeed able to work together, and can yield fruitful results.

The former of the two, the Macedonian-Belgian-French-Croatian-Slovenian co-production “God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunya,” abounds with the comical absurdity present in today’s world. Unemployed, the 31-year-old protagonist of this drama decides to take a stand against men in order to disrupt the equilibrium in their male-centric universe.

The second film, “Stitches,” is a picture partially based on a true story. Centering on the issue of child abduction in maternity wards, the work follows the story of a woman firmly convinced that her son, declared dead 17 years ago, is in fact alive.

“This makes me feel happy and, in a way, it’s a dream come true for me,” Tataragić said about the success of her work. However, as a person who works across the region, she remarked that being a screenwriter anywhere in the region means being kept in suspense about whether your movie is going to be made at all.

“There are numerous projects that go through development hell only to be cancelled in the end. We worked on ‘Petrunya’ for three and a half years and brushed up on ‘Stitches’ for twice as long.”

To have two films shown in one year at a festival like the Berlinale is something approaching a minor miracle.

Post-Yugoslav cinema in Berlin

What paved the way for post-Yugoslav co-productions at the Berlin International Film Festival was the 2003 short motion picture “(A)Torsion,” created by the Serbian director Stefan Arsenijević. Alongside the all-Bosnian cast, the script was penned by the Sarajevan writer Abdulah Sidran, while the film itself was produced by a Slovenian company.

The movie, set in 1994 during the siege of Sarajevo, went on to win a Golden Bear for Best Short Film nine years later, at the same time as the Competition program featured a Slovenian picture, Damjan Kozole’s “Spare Parts.”

Directed by Serbian actor and filmmaker Ljubiša Samardžić, “Sky Hook” (2000) was the first full length post-war entry from the post-Yugoslav region included in the main competition of the Berlinale. It was followed by “Witnesses” (2004) by Croatian film director Vinko Brešan, “On the Road” (2010) by previously mentioned Jasmila Žbanić, and “An Episode in the Life of an Iron Picker” (2013) as well as “Death in Sarajevo” (2016) by famous Bosnian director Danis Tanović, who has been awarded a total of three Silver Bears for these works.

The director of “God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunya,” Teona Strugar Mitevska, noted that making it to the Berlinale is a considerable challenge for any filmmaker.

“I’ve been around in the industry for 15 years already and this is my fifth movie — it’s only now that we’re competing for the awards,” Mitevska explained. “I’ve had a long way to go. Sometimes, it was a jolly ride. Other times, the journey was full of ups and downs. But, as long as you as an artist believe in what you want to achieve, and what you want to say, everything is possible.”

The Berlin International Film Festival is to Mitevska like “a wonder all of us desire.” However, she added that authors still tend not to advertize their creations as “made in the Balkans,” in spite of the fact that motion pictures created in post-Yugoslav countries find their way into the programs of major film festivals.

“God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunya” theatrical release poster.

“In some sense, this is related to our absence from major festivals, though things are looking up,” she said. “It is through communication and cooperation that we can create a Balkan brand more easily, a brand that would provide regional filmmakers with an opportunity to have their films shown at such festivals. This would in turn facilitate distribution of these people’s works.”

Be that as it may, good pictures make it to each film festival.

“You’ve just got to make a good movie first, and it’s bound to find its audience, as well as its spot at movie festivals,” said the creator of “Stitches,” Miroslav Terzić. “Indeed, you need a little bit of luck in the process, and the theme of the given festival should be roughly the same as the theme your movie explores, and you should also make sure that there aren’t a lot of movies dealing with the same issues you want to tackle… Actually, there are lot of conditions to be met so that everything can fall into place.”

Terzić explained his winning formula in film comes down to the theme. “Theme serves as the framework of a particular movie,” he said. “Theme determines the movie. Genres and forms, although important, are not crucial.”

Furthermore, he claimed that themes in the films made in the region put an emphasis on sore subjects, adding that “they stem from the area we live in.”

Creating new, firm stitches

In the end, the sustained effort of surmounting all obstacles to filmmaking is very much worthwhile, according to Amra Bakšić Čamo — one of the co-producers of the motion picture “Stitches” — since “taking part in a major film festival makes a previously modest cinematography more visible; dark horses therefore get the attention of both international critics and international audiences, which would otherwise be impossible to achieve.”

Čamo praised the host city of the festival. “Boasting with politically engaged people particularly sensitive to social issues, Berlin makes for a natural habitat for filmmakers from the region,” he said.

“When it comes to our cinematography, that’s the way it is — it consists of exceptional individuals, and as long as they are around, our cinematography will endure, or at least the illusion thereof.”

Premieres and awards at festivals such as the Berlinale are some of the highest rewards in this respect, along with the promotion of film directors and cinematography itself. However, post-Yugoslav cinematographers stress the importance of regional cooperation, indispensable not only with regard to co-productions, but also in terms of the creative process at large, as exemplified by the pictures “God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunya” and “Stitches.”

“Cooperation is essential — we’re inextricably intertwined with each other in a cultural sense,” Mitevska said. “We share the same history, the same childhood stories, and the same references, so of course it’s normal for us to cooperate. Moreover, it’s necessary to do so. Our team in the Balkans grows with each movie we make, and accordingly, one by one they are met with more success.”

Terzić, on the other hand, argued that even though the making of motion pictures in the post-Yugoslav countries requires regional co-production, everything in this region boils down to political mundanities.

“We never ask questions when, let’s say, a French-German co-production takes place,” Terzić said. “I was born in Yugoslavia and it goes without saying for me to look for people to work with in my neighborhood. After all, this is the road to recovery on which we can heal our wounds for the sake of creating new, firm stitches.”

Apart from being represented by Terzić’s film, Serbia will also feature at this year’s edition of the Berlin International Film Festival as a co-producer of German entry “I Was at Home,” directed by Angela Schanelec. Furthermore, Ivan Marković, the director of photography in this film, teamed up with Chinese filmmaker Wu Linfeng to create “From Tomorrow On, I Will,” selected for the Forum section at the Festival.

Igor Drljača’s movie “The Stone Speakers,” a Canadian-Bosnian-Herzegovinian co-production, is set to premiere within the same program, while a separate section is reserved for Bosnian-Herzegovinian works as well as for those focusing on the process of coming to terms with one’s past.

It includes a French picture titled “Omarska,” created by Varun Sasindran, and a German one titled “Can’t You See Them? – Repeat.,” directed by Clarissa Thieme. In addition, the former is edited by Sarajevo Academy of Performing Arts student Sajra Subašić.

Nihad Kreševljaković is the man who helped the aforementioned German entry see the light of day. Vying for the award in the Berlinale Shorts section, he said that “these movies will provide audiences with an opportunity to gain new insights into painful topics from our pasts.” K