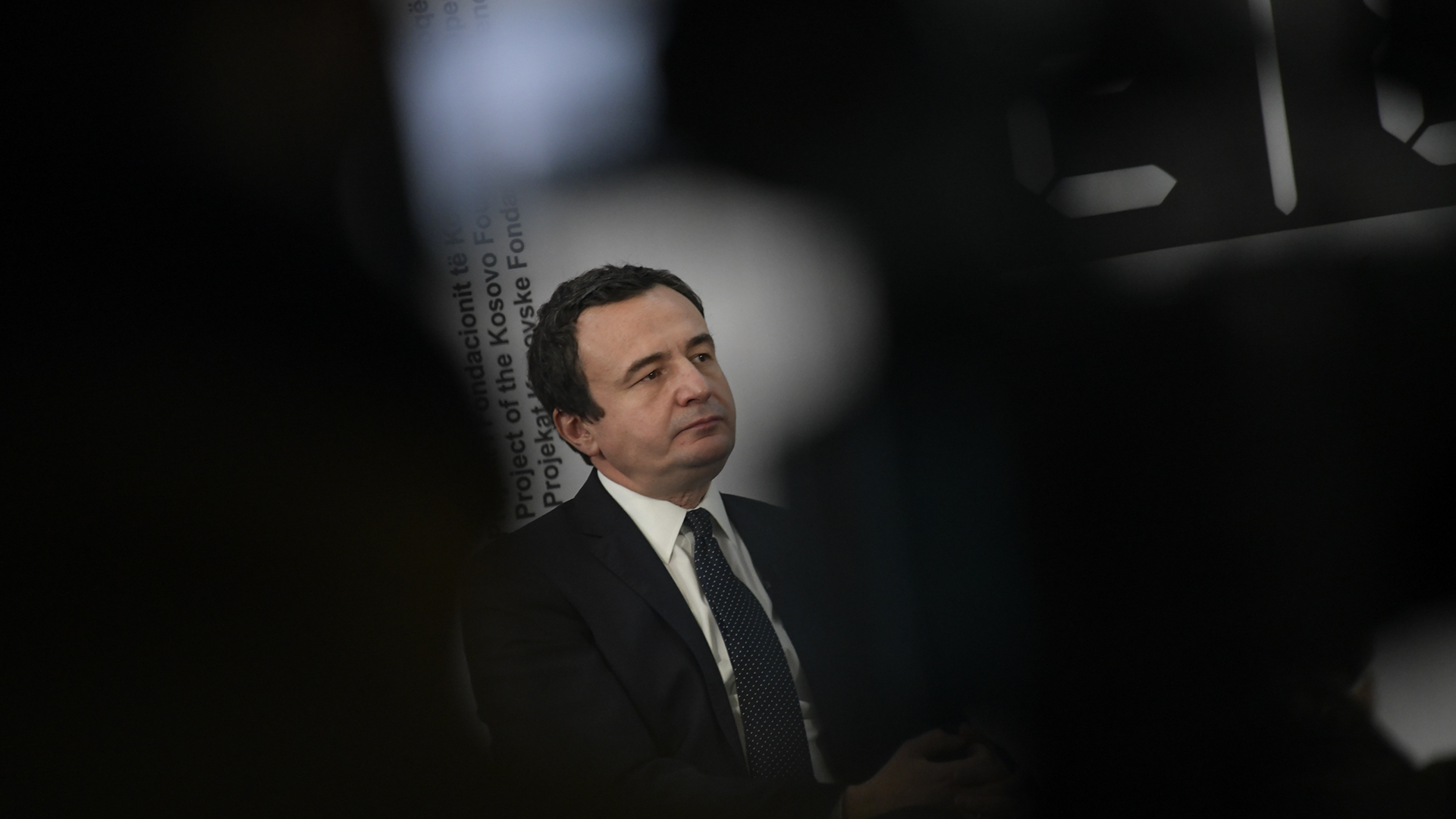

Can Kurti use the moment to start genuine inter-ethnic cooperation?

This critical juncture points toward possible change.

The result is that everyday Kosovo Serbs have had to deal with the consequences of this deep-rooted polarization.

Kurti’s people-centered approach to Kosovo’s governance problems may prove to be a light at the end of the tunnel.

The government must ensure that all the legal obligations and constitutional rights of Kosovo Serbs are being respected on the ground.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.