Erzen Shkololli leaves the directorship of the National Gallery of Kosovo today after four years of attempting to drastically transform the institution. Kosovo 2.0 spent a morning with him, discussing his work and what he feels that his legacy will be. We also spoke to more than 20 national and international artists, curators and art critics about the out-going director’s impact at the National Gallery. There is one thing that they all agreed upon: Shkololli’s shoes will be hard to fill.

The care that Erzen Shkololli puts into his always-impeccable dressing style is a reflection of the treatment that he has tried to give to the institution that he took over on September 6, 2011.

In his first days as director of the National Gallery of Kosovo (NGK), Shkololli had to open an exhibition that went against his better judgment. His first exhibition, edition XI of the Gjon Mili International Photo Exhibition, had already been prepared by his predecessor, Fahradin Spahija, but to Shkololli the show was an alien experience.

Shkololli describes the difference between the Gjon Mili International Photo Exhibition before his tenure, and during it, as like “day and night.” Left: Edition XI in 2011. Right: Edition XIV in 2015.

“It was something which I couldn’t connect with,” he says. “I thought it was also something obsolete which I didn’t believe in.”

Fittingly, four years later, the Gjon Mili International Photo Exhibition, named after the prominent Albanian-American photographer, would also end up being Shkololli’s last exhibition as director of the NGK, as edition XIV opened on August 7 of this year.

For him, the two shows are “like day and night.” And that’s how many have come to view the gallery before and after Shkololli’s directorship.

Hunger For Art: Outside the Institution

Thirtynine-year-old Shkololli is part of a generation of artists who had studied during the 1990s. Education was generally held in houses and private venues (as all public institutions were closed down for Kosovar Albanians by the Serbian regime), and artistic and cultural production was confined within the borders of the country, or even within the ‘underground’ venues of the time.

Following the 1999-war, there was an urge to do more. Shkololli started a collaboration together with Sokol Beqiri, one of Kosovo’s key contemporary artists. They began organizing various curator visits, lectures, exhibitions and educational activities. By 2003, it was formalized into the EXIT Contemporary Art Institute in their hometown of Peja. Until 2006, EXIT would serve as a meeting, networking and collaborative venue for Kosovar artists in a space that was shared with art critic Shkelzen Maliqi’s Center for Humanistic Studies Gani Bobi, and artist Mehmet Behluli’s Laboratorium visual arts lab, which both focused on alternative education projects.

“Before we opened EXIT, we used to work as artists and traveled in the same exhibitions so we met a lot of people,” said Beqiri, while sitting at a table of what is no longer the EXIT gallery, but his EXIT bar.

But Beqiri noted that there were numerous problems facing the artistic community in the first years after the war, including the international isolation of Kosovars and the conservatism of the Academy of Arts at the University of Prishtina. “Kosovo was closed,” he said. “A lot of young people could not travel and the Academy of Arts was, and still is, in the 60s.”

In an article written by local visual artist Majlinda Hoxha for the Kosovo 2.0 ‘Balkart’ magazine edition, a number of up-and-coming local artists, (Academy students after ‘99), described the greatest flaw in the Academy as the fact that it did not open up to conceptual art or experimentation.

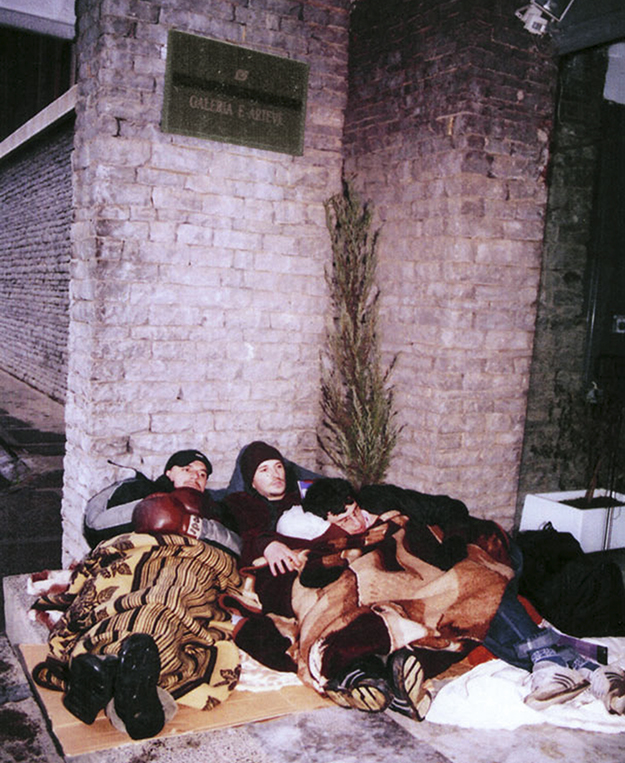

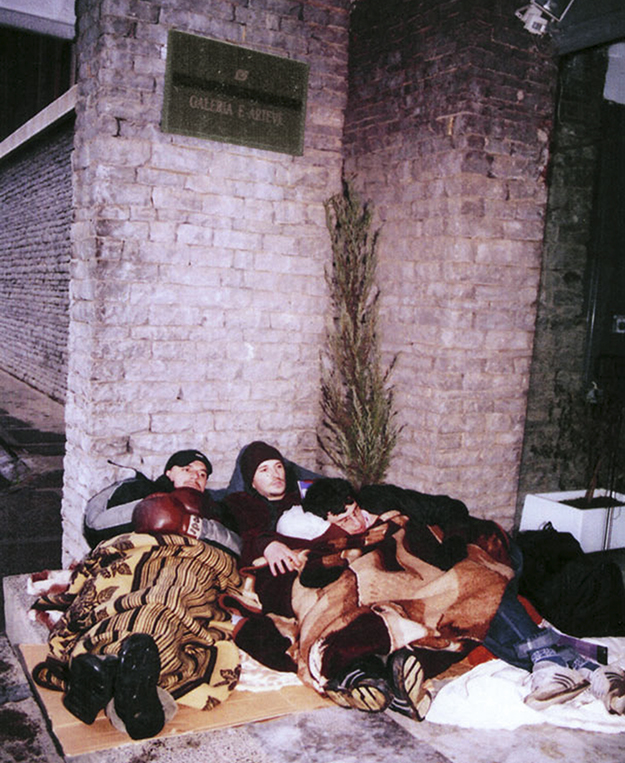

“Waiting for Curator”: A documentation of a night awaiting the arrival of curator Edi Muka outside the National Gallery, which ended up in the exhibition “the fish doesn’t think, ‘coz the fish knows everything.” Photo courtesy of the artists: Lulzim Zeqiri, Jakup Ferri and Driton Hajredinaj.

The Academy’s shared studios did however remain as the only alternative hubs that were permanently open to the independent artistic scene for the first years of the new millennium. Later on, they were joined by independent arts gallery Stacion – Center for Contemporary Art in 2006, and the artist run space Tetris Hapesira Manipuluese in 2010.

But the independent scene would still have to wait for the NGK to embrace the national contemporary art scene as alternative art remained largely alien to the institution during these years. There were a few exceptions, such as the exhibitions “We” (2002) and “Ju” (2003), both curated by Zeni Ballazhi, and which opened up the gallery to young artists. Another notable exception was the 2003 exhibition “the fish doesn’t think, ‘coz the fish knows everything,” by Albanian curator Edi Muka, which was attended by the German curator, Rene Block; the internationally renowned curator would go on to bring Kosovar artists to the “In the Gorge of the Balkans: A Report,” exhibition held in Kassel in 2003, and to the fifth Cetinje Biennale in 2004.

Besides these few examples though, by and large, the gallery was yet to grow.

Shkelzen Maliqi, the country’s most influential arts critic, told Kosovo 2.0 that with previous directors (Luan Mulliqi and Fahredin Spahija), the national gallery had been more of an object for improvisation, with no clear concept or cultural strategy.

“The real independent scene was happening elsewhere,” said Maliqi, who later served as a board member of NGK (2011-2014) during Shkololli’s leadership.

Shkololli remained involved with this independent scene up until his application for the NGK director role, as an artist and through exhibitions such as “Perspektiva” at Tetris Hapesira Manipuluese in 2010, which he curated.

The exhibition “Perspektiva,” held at Tetris Hapesira Manipuluese in 2010, was curated by Erzen Shkololli.

In 2011, Shkololli applied to run the NGK. “I knew what I wanted to do with the institution,” says Shkololli, looking back. “I think we are all obliged as citizens of Kosovo, which is a very young country, to do a contribution — I really wanted, and I still want, to contribute to my country, at least with what I think I know the best.”

Dust Out, Makeup In

Jumping from the local independent scene to being part of an institution wasn’t easy. This was especially so given the mistrust toward public institutions in a country that had declared independence three years earlier in 2008, and where public institutions were largely seen as being politically influenced or driven.

“I was skeptical that he wouldn’t have the support of the artistic community or the Academy of Arts,” said his friend Beqiri. “But he is really tough when he wants something.”

One of the first things that Shkololli did when he arrived at the gallery was to clean up — literally. And once the dust was out, the makeup was brought in.

Shkololli introduced one of Kosovo’s best-known graphic designers to his team; Bardh Haliti. Educated within the Dutch design school, Haliti became responsible for NGK’s visual identity; designing publications, posters and any other material with an NGK stamp on it.

In order to provide a new identity for the gallery, Shkololli quickly appointed graphic designer Bardh Haliti to his team. Above, some of the catalogues designed during the past four years by the National Gallery.

“Erzen [Shkololli] envisioned the National Gallery of Kosovo as a contemporary art space, which could be good enough to be anywhere,” said Haliti. “The real task was always to make something interesting and exciting — not only good enough locally, but also something that could play an interesting role in a larger arts and design discourse. In other words, to build an international institution in an otherwise provincial city.”

For the first four months of Shkololli’s tenure in 2011, the gallery had no remaining funds for exhibitions. Refusing to be perturbed, he pulled out his contacts list and brought in Rene Block to be the first collaborator for the gallery’s institutional program. Block already knew Kosovo from his 2003 visit to EXIT, and so the curator who had led the Museum Fridericianum, in Kassel for 10 years — one of the oldest public museums in Europe and home to the prestigious Documenta contemporary art quinquennial — cooperated with the gallery practically pro bono.

The selection of Block as the gallery’s first curator when Shkololli assumed leadership, and the presence of internationally acclaimed artists at the gallery can be seen as preliminary examples of how things were to be done for the next four years.

Bringing in the Nationals, Bringing Down the Walls

To complement the work of internationally renowned artists, from the very beginning Shkololli also set out to prioritize the promotion of different generations of Kosovar artists.

One such group included paying tribute to deceased artists, such as filigree master Simon Shiroka, and painters Engjell Berisha and Muslim Mulliqi, who were at the forefront of Kosovo’s modern art between the 50s and 70s. Shkololli marked their contributions through retrospective exhibitions and publication of their monographs. In fact, the most visited show since 1999 remains the Muslim Mulliqi “Retrospective” exhibition, celebrated on the occasion of Kosovo’s 7th anniversary of independence in 2015. It had a total of 1,987 visitors.

The Muslim Mulliqi “Retrospective” exhibition was the most visited show at the National Gallery since 1999 with 1,987 visitors.

The second group included contemporary artists who have been working in the field for anywhere between 20 and 40 years, such as conceptual artist Sokol Beqiri and photographer Lala Meredith-Vula.

And the third group included a younger generation of artists, such as visual artists Alban Muja, Petrit Halilaj and Flaka Haliti, who were already making a name for themselves internationally; Halilaj and Haliti would both end up representing Kosovo at the Venice Biennial.

One change that Shkololli introduced during his tenure was to reduce the frequency of the Muslim Mulliqi International Exhibition and the Gjon Mili International Photo Exhibition; both went from annual to biennial competitions (held in alternate years). The idea behind this was to optimize the capacity of the gallery, but also to ensure an increased quality in the works selected for exhibiting.

The director’s initiatives have not gone unnoticed by the artistic community. Internationally acclaimed Albanian installation artist Anri Sala is full of admiration for Shkololli’s work at the gallery. “He has been able to enhance its potential and broaden its horizon and mission, especially knowing that such institutions can be, by nature, weak, inconsistent and fragile in economically poor countries with other priorities,” he said.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, co-director of the Serpentine Galleries in London, gave a lecture at the National Gallery in July 2015.

Shkololli has also drawn plaudits from some of the most influential people in the contemporary art world. Hans Ulrich Obrist is the co-director of the Serpentine Galleries in London. “One of the most remarkable things about Erzen and his work is his collective roles as a gallery director, curator, and also an artist,” he said. “His own personal career has kept him at the cross-section of these roles within the art world, which I think has probably contributed to his ability to understand how each of these levels can be fostered from the ground-up.”

Opening up the Gallery

During Shkololli’s leadership, the NGK has become a significant meeting point for foreign and national artists and curators; it witnessed a renaissance.

Attracting international jurors for various competitions has become the norm, rather than the exception. Shkololli has also looked to bring in prestigious curators to simply meet up with local artists, even if they were not going to exhibit at the gallery.

“Sharing one’s network is imperative,” said Albanian artist, Sala, “especially when it comes to countries such as Kosovo, Albania or other countries in the region, because for the time being the access of the international curators or artists to the local scenes is sporadic and often not consistent.”

In 2012, two world-class names came to curate Shkololli’s first Muslim Mulliqi International Exhibition for contemporary art, called “It Doesn’t Have to be Beautiful Unless it is Beautiful.” They were Galit Eliat, founding director of The Israeli Center for Digital Art, and Charles Esche, director of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven — which in 1936 became one of the first public museums for contemporary art to be established in Europe.

For the ninth edition of the Muslim Mulliqi International Exhibition (2012), French artist Laurent Mareschal re-created the floor of a Palestinian home.

Then there was the Henry Moore Exhibition in 2014, which brought the works of this British sculptor to Kosovo. And in 2015, came the exhibition“Thirty One”; an overview of part of the works of the Kontakt Art Collection, which focuses on the art from Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe that accompanied social and political developments over the past decades.

Christine Frisinghelli, former director of the reputable Camera Austriamagazine, says that Shkololli’s work will prove to be a “benchmark for the future development of contemporary art in Kosovo.” For her, Shkololli’s choice of topics, artists’ positions and acting curators are altogether an important contribution in a context “where young practitioners in the field of visual arts are aiming at positioning their work and thoughts in a globally competing market.”

Frisinghelli herself curated the first Gjon Mili International Photo Exhibition that Shkololli organized, in 2012. She is also part of the jury for the 2015 Gjon Mili 2015 edition, which has been curated by Richard Birkett.

Frits Giertsberg, curator of the 2013 Gjon Mili International Photo Exhibition believes that “Shkololli has put Kosovo on the international art map.” And Vasif Kortun, director of Research and Programs of SALT(Istanbul), goes as far as to say that, “there has not been a better institution in Southeastern Europe for a very long time, including Macedonia, Bulgaria, Albania, and Greece.”

Kosovo participated in the prestigious Venice Biennial for the first time in 2013, where artist Petrit Halilaj was chosen to represent the national pavilion.

The climax of this international presence and exchange came in 2013 with Kosovo’s first participation at the Venice Biennial, the world’s most prestigious international art event. Under the directorship of the National Gallery, Shkololli was the exhibition’s commissioner and once again chose to work with a combination of international and Kosovar partners; Austria’s Kathrin Rhomberg and the young Kosovar artist (who has also had international acclaim), Petrit Halilaj.

A Reformist Abroad and a Revolutionary at Home?

While Shkololli deployed a clear strategy for the NGK, questions have been raised as to whether his artistic program is considered groundbreaking due to the quality of content or to the fact that the level that preceded him had set a low benchmark.

When asked if Shkololli has been a reformist or a revolutionary within the walls of the institution, critic Maliqi shook his head, as if none of the options given suited the soon-to-be former director of the NGK.

“In the sense of contemporary art, he has a conservative approach,” said Maliqi. “He is doing something that in the European world, it was done 30 or 40 years ago… but for us is kind of… not a revolution. But he has been opening new views, organizing excellent exhibitions, promoting new arts, not only for us but for the region too. He is definitely a good connection with the contemporary art scene in Europe and abroad.”

For Albert Heta, director of Stacion–Contemporary Art Center, one of the few independent art spaces based in Pristhina, the gallery resembles other public institutions around the world that are generally “normalized.”

“You will never find a work with a challenging content being exhibited at the National Gallery during this time, a work which is not politically correct, that generates much debate about an issue not so discussed,” he said.

Eriola Pira, an Albanian curator, visual culture theorist and art administrator who has collaborated with the gallery on the Artists of Tomorrow Award since 2009, has some sympathy with Heta’s views. While saying that Shkololli’s leadership has been a “game changer,” far beyond Kosovo and the region, she also views his tenure with a critical eye.

“For the most part, the exhibitions of the past few years have played it rather safe and they haven’t really managed to generate much by way of excitement or antagonism,” she said. “There haven’t been works or artists that have captured the public’s imagination or generated a discussion within artistic circles. I’m not sure if Erzen is at fault, but I do think that the director can, and should, encourage both curators and artists to take risks.”

Faced with the criticism that he’s not tried to push boundaries, Shkololli recalls Sokol Beqiri’s retrospective show in the fall of 2014, and the last edition of the Muslim Mulliqi International Exhibition celebrated in the same year, which tackled contemporary political issues. Looking back though, he also points to the artistic scene beyond the walls of the NGK gallery.

Sokol Beqiri’s “Retrospective,” held in 2014, displayed some of the artist’s best works. Beqiri is considered as a key figure of Kosovo’s contemporary arts.

“I think this has to come from the artists,” says Shkololli. “It’s not that the National Gallery shouldn’t support these voices, that’s not the case at all… but I think that I haven’t seen anything [like that] in the independent arts scene, or in any off-space in Kosovo. For me the quality of the works, of the production, is the criteria — a scandal doesn’t make a good work.”

To be Continued

Although proud of his achievements, Shkololli is well aware that there is much left to be done. He mentions the forgotten collection of the gallery — the approximately 900 works that the gallery has acquired, which remain in a depot due to lack of space or venues for permanent exhibition. Many of them require restoration, which would require additional funding.

Shkololli continues talking about the need for a museum for modern art, for which, he says, Kosovo lacks the professional capacities. For that reason, he is especially proud of the educational programs that he has initiated. Earlier this year he introduced the Public Program of Lectures, through which he hopes to have made a small contribution to stimulating interest in the scene’s growth. Set up in the manner of public talks and lectures, one of the participants included Adam Szymczyk, artistic director of the Documenta 14 quinquennial exhibition; alongside the Venice Biennial, Documenta is the most important contemporary art event in the world. From September 1, 2015, Prishtina’s elementary and high schools will also bring students to regularly visit the gallery.

From September 1, elementary and high school students from Prishtina will be regularly visiting the National Gallery.

However, when considering what the future holds for Kosovo’s art scene, there are some issues that are beyond Shkololli’s control. In February this year, NGK’s board was dismissed, just six months into a four year tenure, in a move that was widely perceived as an attempt by the new Minister for Culture to garner closer political control of the arts; similar purges were made to the boards of both Kosovo Cinematography Center and the National Theater of Kosovo around the same time.

Earlier this week the University of Prishtina’s Faculty of Arts failed to have any of its academic programs accredited by the Kosovo Accreditation Agency and just yesterday, there was a sense of deflation in artistic circles as the names of the applicants who have been shortlisted to become Shkololli’s successor were announced; all of the nominees are current Ministry of Culture technocrats.

What the immediate future holds for Shkololli personally, he doesn’t want to disclose just yet. But one thing is for sure, he will stay in Kosovo. As for the next director of the gallery, the bar has been set high, but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t go higher.

“Whoever takes the responsibility has to work a lot, be sincere in their work, and bring something that I didn’t bring,” says Shkololli. “It was never my intention to make it easier for any person.”K

Photos: Courtesy of the National Gallery of Kosovo; Atdhe Mulla.