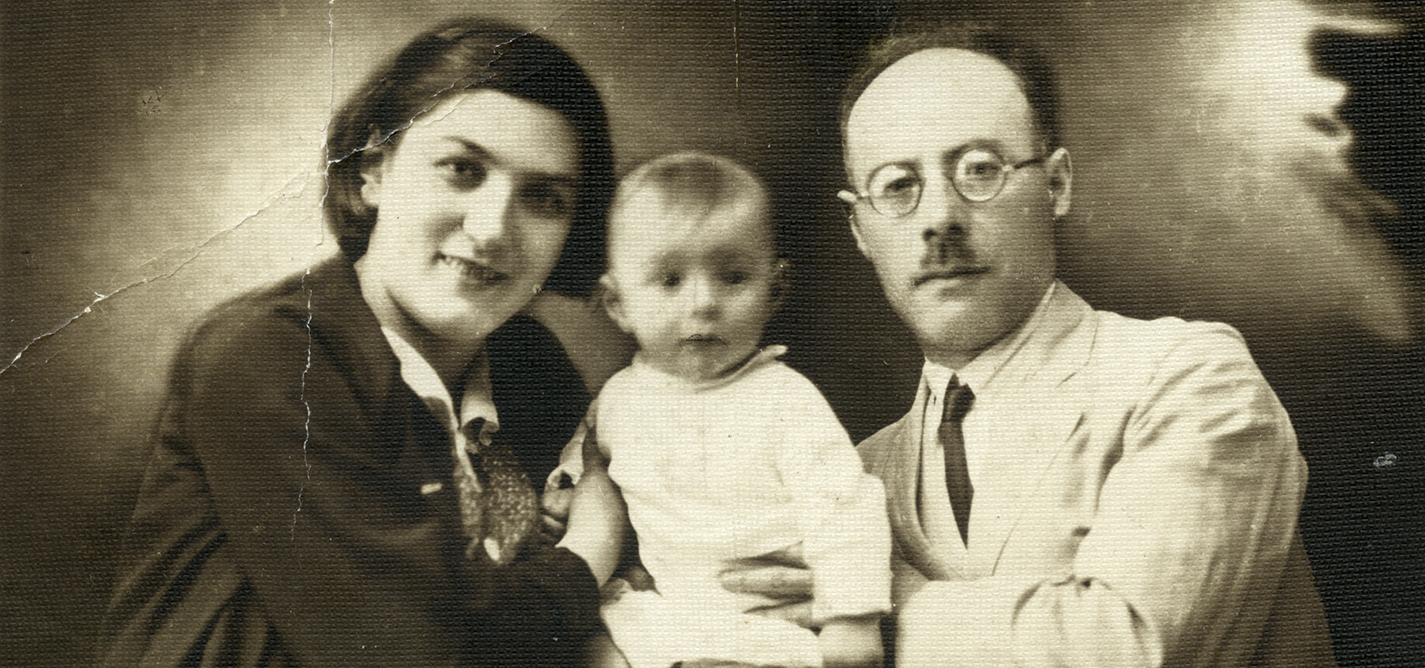

How a Jewish doctor found his home in Prizren

The man who saved countless lives in Prizren.

Dr. Teitelbaum most probably saved his life, and so I am here today, thanks to him, piecing a story together — a story that has been haunting me since last summer.

By the time he was walked into our family home in 1941, it felt as if he had always lived there.

He left an indelible mark in my hometown and the collective memory of its people.

Teuta Skenderi

Teuta Skenderi is a Kosovar Albanian translator, teacher and author based in London. She is currently researching the forgotten histories of her community, and their role in the rescue of the Jews in WWII.

This story was originally written in English.