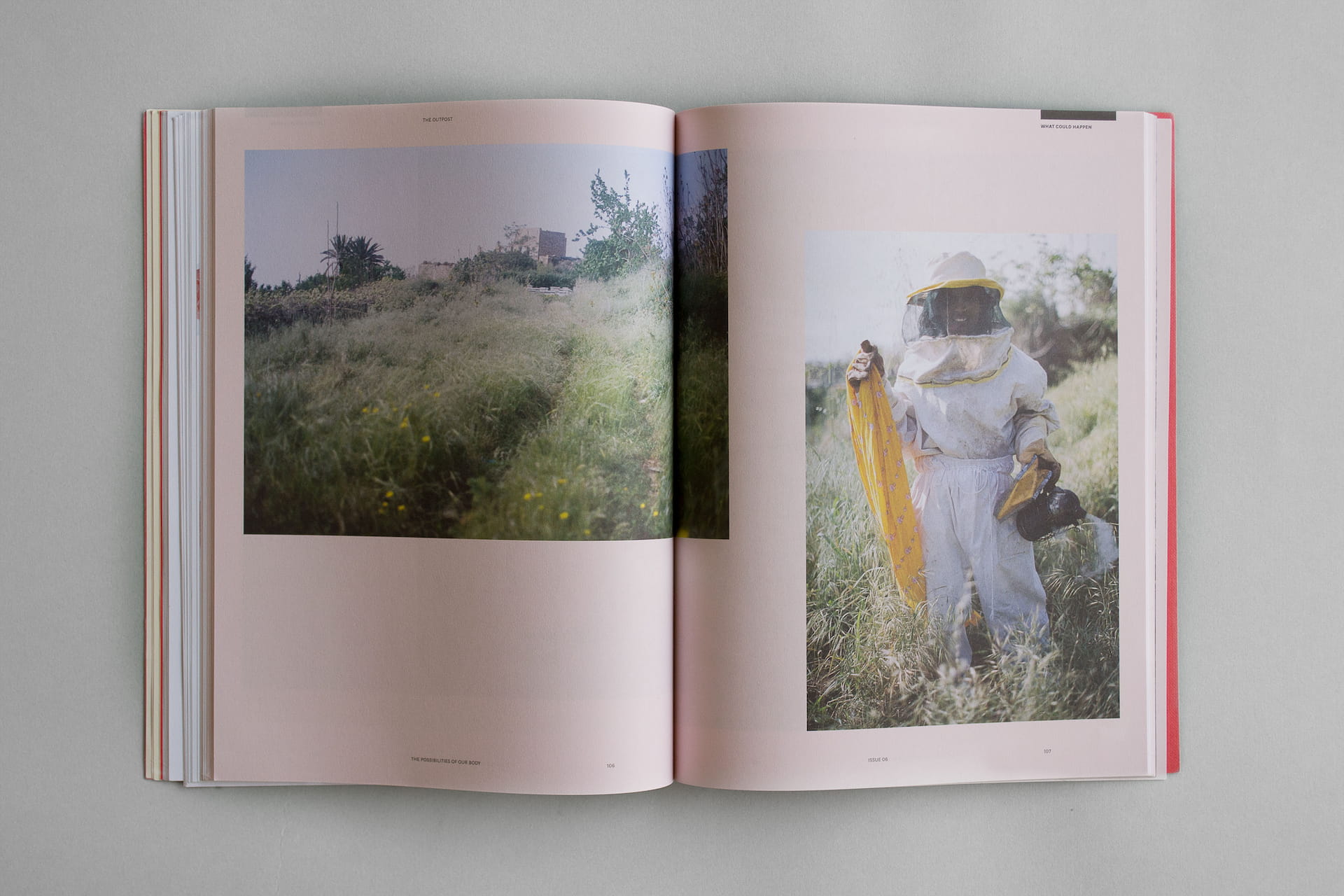

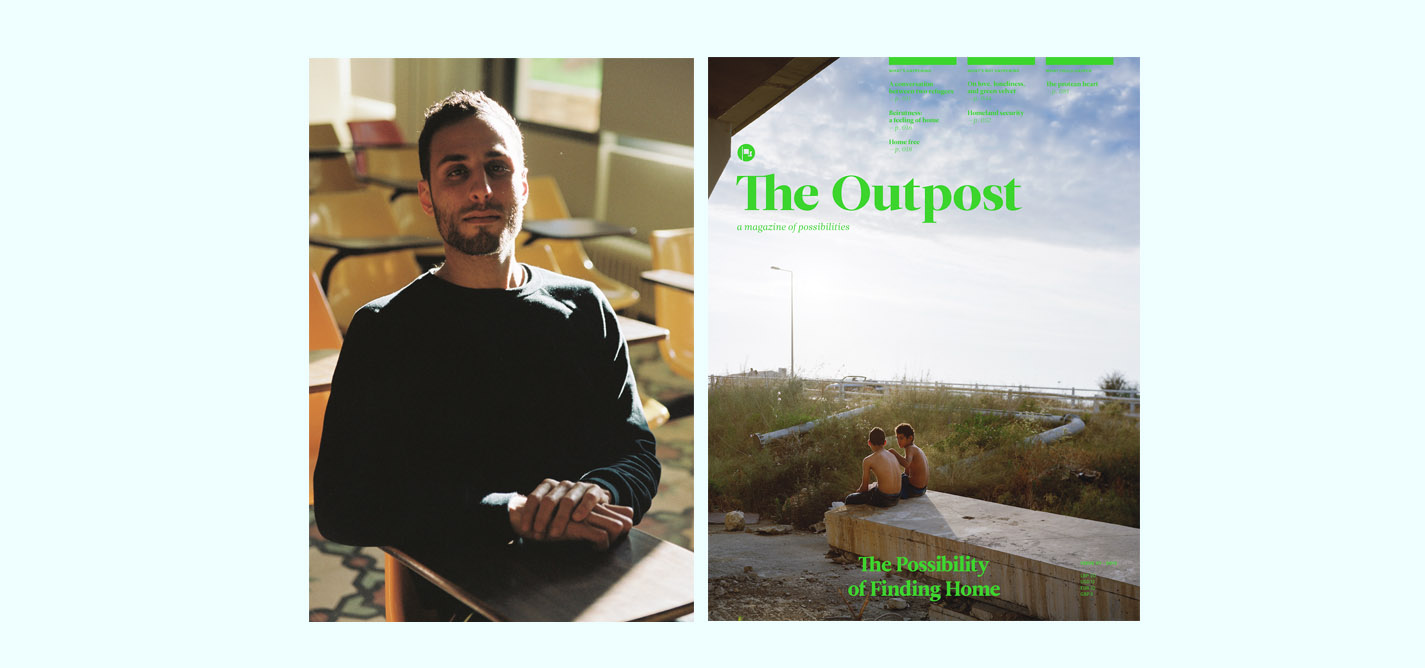

Ibrahim Nehme: Change begins in our imagination

Beirut-based magazine founder talks about the power of the media to provoke radical change.

The impact of imagination

Workshop: “The Lifecycle of an Idea”

Cristina Marí

Cristina Marí is a board member of K2.0. Cristina has a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University Complutense of Madrid in Spain and the University of Bucharest, Romania.

This story was originally written in Albanian.