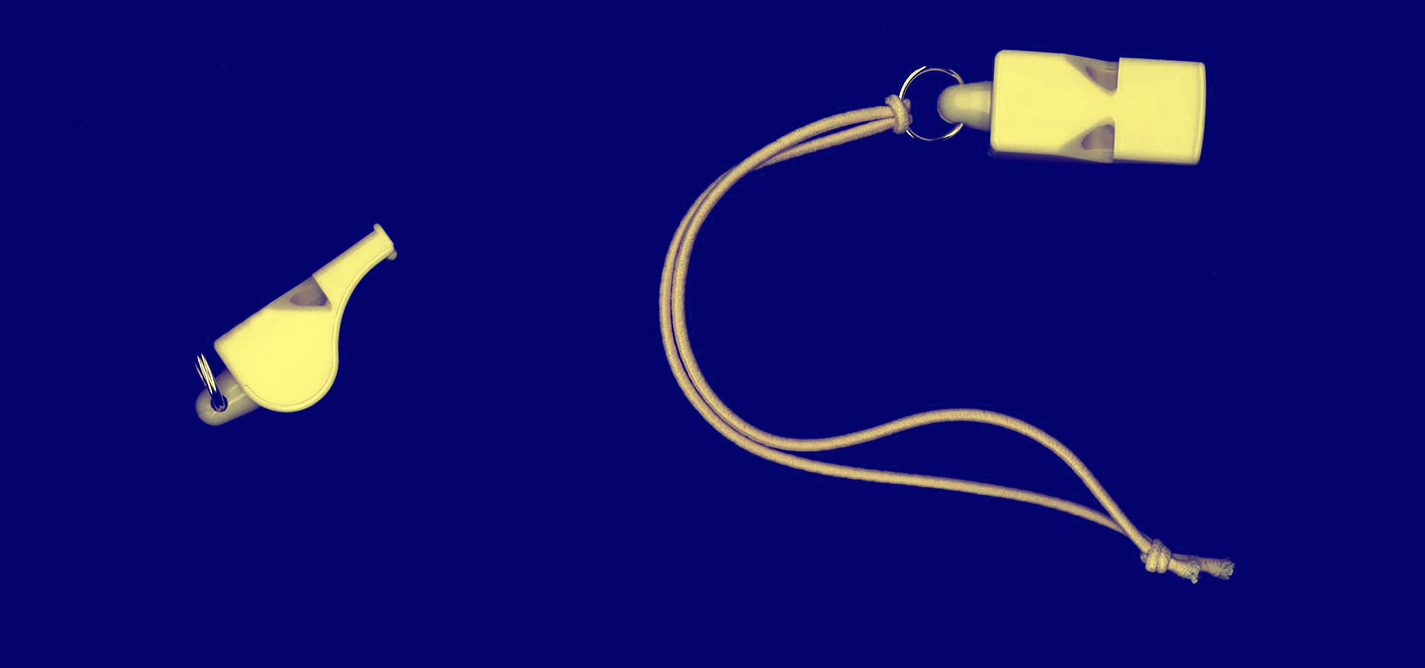

Kosovars need help to speak out

EULEX allegations raise the issue of whistleblowing.

|28.11.2017

|

If well utilized, such a statute could empower employees in both private and public institutions to reveal any wrongdoings or corruption in their respective institutions.

Eraldin Fazliu

Eraldin Fazliu is a former journalist at Kosovo 2.0. Eraldin completed his Master’s on ‘European Politics’ at the Masaryk University in the Czech Republic in 2014. Through his studies Eraldin became interested in the EU’s external policies, particularly in promotion of the rule of law externally. He is a passionate reader of politics and modern history.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in Albanian.