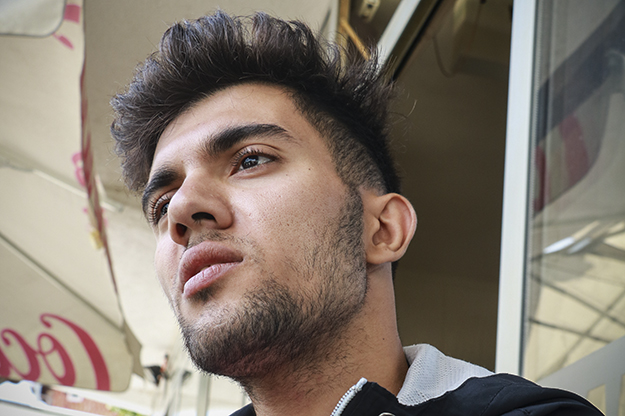

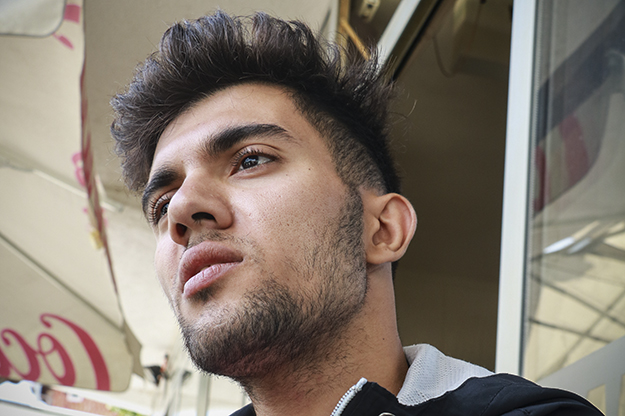

On an afternoon in early September, 24-year-old Ali Fadel sat and enjoyed a Double Force energy drink at Cafeteria Vivace near the Asylum Seekers Center in Magura, Lipjan.

Ali, a Syrian refugee, would come to the cafe for a break and to use the internet to communicate with loved ones outside of Kosovo, as do many of the asylum seekers in the area.

Kosovo is not an important topic in these conversations, be it over the phone or around the table, where he showed the photo of his two-year-old daughter, who, he said, was waiting for him in Germany.

Ali was in the middle of his own travel odyssey; his intended destination was still 2,000 kilometers away, similar to the distance he had already traveled to reach Kosovo from Syria.

Ali used to live with his mother, father and brother in the city of Deir ez-Zor, until 2013, when the war made it impossible for him to stay. He explained that an explosion in their house that year had killed his father.

The ongoing war in Syria, which broke out initially in 2011 following a civil uprising as part of the Arab Spring, is primarily discussed in Kosovo in the context of the radicalization of young Kosovars. Several hundred Kosovars were reported to have traveled to Syria in 2012-13 to join the the Islamic State (IS), one of multiple factions in a complex and ongoing conflict, which has also seen intervention from foreign states including, the U.S., Russia and Turkey.

Ali Fadel, 24, passed through Kosovo in September on his way to Western Europe. He is escaping the civil war in Syria, where he says his house was destroyed and his father killed. Photo: Uran Krasniqi.

Ali, as well as his mother and brother, is part of the more than 5.6 million civilians to have moved in the opposite direction out of Syria, fleeing as refugees; more than 6 million others are displaced within Syria.

Many Syrian refugees first flee to Turkey, where Ali’s mother and brother remain. From there, tens of thousands have continued through the Balkans on the so-called ‘Balkan Route’ and then continue west. The same path is followed by many others from the Middle East and Africa who are looking to escape conflict, poor economic conditions and human rights violations.

Ali’s travel companion, 22-year-old Palestinian Otman Ilmotaki, said he first traveled from Palestine to Syria in June 2017. In Syria, he said he paid 1,200 euros to smugglers to take him to Turkey. In Palestinian territories, in addition to periodic conflict, human rights violations persist as a critical issue.

“I remained in Turkey for a year to make some money,” said Otman, flipping through a number of photographs on his phone from his work in Turkish cities. “I worked in restaurants; I would wash the dishes.”

Otman Ilmotaki left Palestine last year, heading to Syria before stopping in Turkey to earn money before continuing his journey west. Photo: Uran Krasniqi.

With the money earned in Turkey, the pair paid another 500 euros to cross the Turkish-Greek land border. Despite the risk of drowning, passage via sea from Turkey to Greece costs those on the move even more, from around 880 to 7,000 euros for the trip according to the UN’s 2018 Global Study on Smuggling of Migrants.

The director of Kosovo Police’s Directorate for Migration and Foreigners, Rahman Sylejmani, explains that Kosovo is not on the main route currently being used by migrants in the Balkans as moving via Kosovo — which does not border any EU member states — poses the problem of crossing yet another border and prolonging the journey.

Sylejmani says that since the closing of the route leading through Macedonia, Serbia and into EU member state Hungary in 2016 — when these countries tightened their border security at the request of EU countries, particularly Austria — the ‘New Balkan Route’ has been through Greece, Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia.

The number of migrants registered in Albania in 2018 is more than 100 percent higher than last year, while at the border between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, thousands of migrants remain in tents in Bihać and Velika Kladusa, unable to cross into the EU. Conditions at this border have come under strong criticism, with Médecins Sans Frontières highlighting push-backs and violence against migrants on the Croatian side.

While Kosovo may not be on the main route, dozens of migrants still attempt to pass through each year. Kosovo Police’s Directorate for Migration and Foreigners, told K2.0 that in 2018 up until August, 146 people had been registered illegally crossing the Kosovo border. Last year, 147 such crossings were registered, while 307 people were known to have entered illegally in 2016.

A report issued by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in August 2018, states that most migrants and asylum seekers arriving in Kosovo are from Syria, Turkey, Palestine and Libya.

Migrants entering Kosovo come mainly through Albania and Macedonia. According to Sylejmani, the majority of migrants coming through Albania enter near to the regular crossing point at Vërmica, while those through Macedonia enter from trails near to the Hani i Elezit crossing point.

Ali and Otman came to Kosovo through Albania after having failed several times to enter Montenegro. Ali said Montenegrin police forced him to return, using violence against him during his attempt to cross the Albania-Montenegro border.

“They hit me with a police baton,” he said. “Then we returned to Albania.”

The Montenegrin Police Inspectorate did not respond when contacted about the Syrian’s claims. There have been reports in regional media that NATO’s most recent member country is tightening its border with Albania; since August 17, Montenegro has deployed military troops to the border in an increased effort to prevent illegal migration.

“We remained for three days [in Albania] and then came to Kosovo,” Ali said.

According to Ali, since he and Otman left Greece, they hadn’t paid any smugglers, but had instead used smartphones to find routes from Greece to Albania and then to the border with Montenegro before coming to Kosovo.

A month after K2.0 had met the pair at the cafe in Magura, both had moved on from Kosovo, as most migrants who report to the Asylum Seekers Center do.

Ali’s sights had been set on reaching his daughter and girlfriend in Duisburg, Germany. “I won’t stay here much longer,” he had said in September. “I have no time; the weather will get worse. It will be very cold to cross through and sleep in the mountains.”

Otman had been hoping to join some friends in the Netherlands, which is not far from Duisburg.

Police director Sylejmani says that since the route from Kosovo to Montenegro is more difficult to take due to the mountainous terrain, most migrants tend to cross through Leposavić into Serbia.

“Mostly through Jarinje … and a small number [cross at] Brnjak,” he says, referring to border crossing points in the north of Kosovo; the state’s institutions have little real control in this part of the country, and border crossing points here have long been linked to the smuggling of goods.

Failing to provide protection

Kosovars are well acquainted with the suffering that often accompanies migration, as Kosovo was itself a source of intensive migration to the West during the ’90s and also saw large waves of people leaving at various points in the preceding decades.

Large numbers of Kosovars have also attempted to leave the country in recent years. The Ministry of Internal Affairs, referring to Eurostat statistics, claims that the number of illegal Kosovar migrants to the EU from 2013-17 alone totaled 123,415 people, while that of returnees based on expulsion orders was 49,410.

This experience does not seem to have resulted in a more generous or understanding treatment of people on the move from Kosovo’s authorities.

When a migrant from Algeria died at the Asylum Seekers Center earlier this year, the topic failed to catch public attention.

Twenty-eight-year-old Rabehi Lamine had applied for asylum on September 19, 2017. On the morning of February 24, 2018, he was found unconscious on his bed by the Center’s security staff.

Lipjan’s Emergency Service’s records state that the ambulance arrived at the Center at 8:30 a.m.; after the paramedics had provided medical assistance within the ambulance to bring him back to consciousness, the patient was delivered to Prishtina’s University Clinical Center of Kosovo (QKUK) with a pulse of just 50 beats per minute and blood oxygen levels of 85 percent (the normal percentage is 95+, according to the World Health Organization).

Javorka Prlinčević, a prosecutor at the Basic Prosecution of Prishtina, which has closed the case investigation, says the Algerian’s cause of death was cardiac tamponade.

According to Prlinčević, the forensic report found that Lamine passed away after consuming sedatives without a doctor’s prescription.

“He consumed drugs that weaken the blood vessels,” says the head of the Asylum Seekers Center, Fitim Zariqi. “The security staff say there was no noise or problems in terms of a quarrel [amongst asylum seekers] or anything of the sort. Doctors confirm that there were no signs of any attack.”

Based on a Special Needs Assessment Guide document for staff at the center, asylum seekers should be asked whether they are addicted to drugs and/or alcohol, and an assessment must be made as to whether they are in need of psychological or psychiatric assistance. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ Regulation on Functioning of the Asylum Seekers Center, asylum seekers with suicidal tendencies should be placed under special surveillance.

In February this year, 28-year-old Rabehi Lamine died after being found unconscious at the Asylum Seekers Center near Lipjan. Few details have been published about his death.

But sociologist Ismajl Musa, who offers social services at the center, and was on duty when Lamine died, says that the asylum seeker had declared no addiction and did not show any signs of trauma or drug abuse.

“I met him two or three times,” he says. “He seemed like a stable person.”

Lamine’s body remained in the QKUK morgue for more than a week, before being transferred to Istanbul and returned to Algeria via an Istanbul-Algiers flight on March 6.

As Algeria does not recognize the state of Kosovo, and the two countries have no bilateral agreements, the only embassy in the region that could have engaged in Lamine’s case was the Algerian Embassy in Belgrade. Contacted by K2.0 to ask about any involvement in the case, the Embassy failed to respond.

Within Kosovo, there was no press release about Lamine’s death or its investigation published on the websites of any of the relevant institutions; the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Kosovo Police, or the Basic Prosecution of Prishtina.

Artan Murati, a researcher at democratic accountability NGO Kosovo Democratic Institute (KDI), says the Ministry of Internal Affairs should have informed the general public about the case.

“It’s a case involving a foreigner that nobody knows anything about. The least that could have been done was to inform the public about it with a press release,” he says. “As citizens, we have the right to be informed about [the death].”

Zariqi says that Lamine had only stopped to “rest” in Kosovo since he was ultimately trying to reach Western Europe, as are the majority of people on the move in Kosovo.

In the meantime, those only intending to pass through often still apply for asylum — 130 out of 146 people who crossed the border illegally as of August 2018 had done so. This tends to be more of an administrative step for most however, providing them the legal right to stay in Kosovo while their request is being considered, as most have little intention of staying in Kosovo long term.

In recent years, Kosovo has also given Temporary Protection — an immediate and short-term protection status for displaced persons — to 15 people, the majority of whom were from Syria and Palestine.

According to Kosovo’s asylum legislation, those who are successful in their asylum application may be granted Refugee Status, or a lesser form of protection termed Subsidiary Protection Status, if they are in danger of persecution in their country of origin. The Ministry of Internal Affairs must decide upon the application for asylum within 6 months, or 9 months in certain circumstances.

If an asylum is rejected, the party has a right of appeal to the National Commission for Refugees and subsequently to domestic courts. As of September 2018, this Commission had received 10 complaints. However, the Commission has only decided in favor of the complainant once, granting Subsidiary Protection to a citizen of Democratic Republic of Congo in 2014.

Civil Rights Program Kosovo (CRP/K), an organization founded by the Norwegian Refugee Council in 1999 and which offers legal advice to asylum seekers, says that Kosovo had not granted Refugee Status to anyone before this year. Based on their calculations, only 12.8 percent of asylum requests have been approved; this compares with 46 percent of successful applications in EU countries, where most asylum seekers actually intend to stay.

Kosovo’s Ministry of Internal Affairs says that Refugee Status has only been granted to 35 people.

The first, on March 28 this year, was Turkish citizen Uğur Toksoy.

According to BIRN, Turkey had requested the extradition of Toksoy on the grounds that he was part of the Gülen movement headed by exiled cleric Fethullah Gülen, who himself was recently subject to a rejected extradition request by Turkey to the U.S., where he has been granted permanent residency. The movement has been dubbed the ‘Fethullah Terrorist Organization (FETO)’ by Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who has repeatedly claimed it was behind the military coup attempt in Turkey in 2016.

Toksoy was arrested by Kosovar authorities in October 2017, but the courts decided he should not be extradited. “For a country that aspires to the values of Western Europe, the connection with Erdoğan is not good,” Toksoy told BIRN earlier this year.

He was speaking in the wake of events that saw Kosovo make international headlines for what Human Rights Watch termed a “callous disregard for human rights and rule of law.”

Back on March 29, the day after Toksoy’s asylum request had been accepted, six Turkish citizens with Kosovo residence permits had been arrested and handed over to Turkey, despite the latter’s deteriorating record on human rights in recent years.

The deportation of Mustafa Erdem, Yusuf Karabina, Cihan Özkan, Kahraman Demirez, Osman Karakaya and Hasan Hüseyin Gunakan — five educators, plus a doctor — resulted in protests on Kosovo’s streets, an extraordinary session of the Kosovo Assembly and endless political mudslinging. (It later emerged that Hasan Hüseyin Gunakan had been deported in error, in place of Hasan Hüseyin Demir, whose whereabouts are unknown.)

Even today, more than six months later, the precise details of the circumstances surrounding the deportations remain unclear.

What is known is that the Directorate for Migration and Foreigners within Kosovo Police had issued a removal order for six individuals after the Department for Citizenship, Asylum and Migration within the Ministry of Internal Affairs terminated their residence permits (Osman Karakaya’s residence permit had reportedly expired two months earlier). That decision followed an assessment by the Kosovo Intelligence Agency (AKI) that they posed a threat to the country’s security.

The KIA assessment was never published, but Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj is quoted by Voice of America as saying that the agency’s file claimed that the individuals in question made dubious financial transactions that could have brought risks to Kosovo. Haradinaj himself has expressed outrage at the whole affair, and immediately dismissed Interior Minister Flamur Sefaj and AKI head Driton Gashi on the basis that they had not kept him informed of events.

In April, Kosovo’s Ombudsperson issued a report with his findings in the case. The Ombudsperson report says that, in February, Turkey’s Ministry of Justice had made a formal request to Kosovo to extradite two of their nationals — Kahraman Demirez and Yusuf Karabina — who they suspected of terrorism.

According to the same report, despite the fact that Kosovo’s Ministry of Justice passed the case to the Prosecution, the latter did not file the suit concerning the two Turkish citizens. This step broke the legal chain of actions for the extradition of Karabina and Demirez, which based on the Law on International Legal Cooperation in Criminal Matters (Article 23) should have been approved by the competent court. A representative of the Basic Prosecution is quoted as saying that the investigation was not initiated, “having public knowledge about the human rights situation in Turkey.”

“In this way [by not following the legal procedures for international cooperation] the deportees were denied the right to be heard and judged by the competent public authority,” the Ombudsperson found.

Similar to the allegations against Uğur Toksoy, Turkey’s President Erdoğan insisted that the six Turkish nationals deported from Kosovo were senior representatives of the Gülen movement; now in Turkey, they are facing terrorism charges. Turkey has been criticized this year by Freedom House for showing “increasing evidence of extrajudicial ‘disappearances’ and routine torture of political detainees.”

Following complaints from the family members of those deported, on November 13, the Basic Court of Prishtina decided to annul the decision revoking the residence permits of deportees Mustafa Erdem, Yusuf Karabina and Cihan Özkan. The court had, amongst other things, obtained an AKI document regarding the case.

“The main ground on which residence permits were revoked, which was their alleged threat to national security, was rejected by the court,” says Urim Vokshi, the lawyer representing the deportees’ families. According to Vokshi, the court is expected to decide soon about the other three deportees.

However, while the court’s decision may bring some sense of legal justice, it does not bring the family members back their loved ones.

In the wake of the scandal, Kosovo’s legal framework regulating enforced deportation has come under scrutiny, with critics saying that the legislation itself violates fundamental human rights.

Based on Article 6 of the Law on Foreigners, a residence permit may be revoked following security assessments made by AKI, which does not have to justify its decision; if the foreigner is considered a threat to national security, usual protections against enforced removal to a country where there is a reasonable doubt that they will be subjected to torture and/or inhuman or degrading treatment, are superseded (Article 100).

The right to appeal an enforced deportation order is technically provided, including through the courts. However, Article 98 of the Law on Foreigners, and the law amending it — which was agreed in April 2018 and entered into force in May — states that an appeal does not suspend the decision for enforced deportation if they have been assessed to pose a risk to state security or public health.

Ombudsperson Hilmi Jashari says this fact constitutes a violation of human rights, specifically Article 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which regulates the right to ‘effective legal remedy’ and is directly applicable in Kosovo due to Article 22 of the Constitution.

“The entire weight of the phrase ‘effective legal remedy’ lies in the word ‘effective,’ namely that it has an effect on the individual and is accessible, fast, and useful,” Jashari says. “Article 13 of the ECHR [which provides for the right to appeal or an effective lawsuit] should be the measure preventing state’s arbitrariness because the lawfulness of a state is measured by the arbitrary actions it might take.”

Researcher Qerim Qerimi, professor of international law on human rights at the University of Prishtina, agrees that the forceful departure of Turkish citizens breached international law.

“As a bare minimum, any national or non-national residing in a country, in this case Kosovo, should enjoy the right to a fair trial,” Qerimi says. “In other words, such decisions should come as a result of deliberation and court rulings.”

The European Parliament Rapporteur for Kosovo, Igor Šoltes, also agrees that Kosovo’s actions were in violation of international human rights and says they were also inconsistent with European standards.

“I have written to both the president and the prime minister that Kosovo should fully respect the judicial proceedings in line with European standards,” Šoltes says. “All actions should promote universal respect of human rights.”

On April 4, the Kosovo Assembly voted to establish an investigative commission for the case which has so far interviewed dozens of senior officials.

In his report, meanwhile, the Ombudsperson says, that the competent authorities took action, “without coordination between institutions on the grounds of their mandates and lacking transparency, which is the main principle of good governance in a country.”

Yet, the executive authorities still back their actions.

Valon Krasniqi, director of the Department for Citizenship, Asylum and Migration within the Ministry of Internal Affairs, says there have been other similar cases in which the same procedure was followed to revoke the residence permits of other foreigners.

According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, on April 10, 2018, the residence permit of a Jordanian national was revoked in a similar way to the case of the Turkish nationals, based on an AKI assessment. The Jordanian citizen had been granted a residence permit since 2002, but according to the Ministry, on May 2 was subject to enforced deportation to Jordan by Kosovo Police.

“The procedure went the way it usually does: The requests [to revoke the residence permits of the Turkish nationals] came from AKI to the minister. The minister then forwarded it to us. There was nothing extraordinary about it,” Krasniqi says, adding that, in line with the law, AKI did not provide a justification for its request.

While the Assembly and the courts are still hoping to shed full light on the case of the Turkish nationals, Edward Joseph, a researcher on the Balkans at Johns Hopkins University in the United States, said in an interview for Voice of America that Kosovo seemed to “kneel when faced with the Turkish pressure” to deport the people.

On November 11, after President Hashim Thaçi met with Turkey’s President Erdoğan, he tweeted: “Erdoğan is a true friend and a great supporter of Kosovo.”

Meanwhile, every one of the 35 people that has been granted Refugee Status by Kosovo is a Turkish national.

When a quest for freedom ends behind bars

While the ignominious treatment of the six Turkish citizens triggered a political backlash and much media debate in recent months, the struggles facing those in Kosovo as part of their migration along the Balkan route to Western Europe rarely make it into public consciousness.

In the past three years, just over 200 people from 27 different countries have ended up at the Detention Center for Foreigners in Vranidoll, near Prishtina.

The Detention Center is intended for people who are detained entering Kosovo illegally but who do not seek asylum, or those whose asylum requests are rejected and who do not leave Kosovo within 30 days. By law, they may be held here for up to a year while arrangements are made for their enforced return to their country of origin, although in reality most people’s detention is shorter; in August 2018, just four people were here.

That’s partly because many of the detainees don’t wait for potentially lengthy enforced return proceedings to run their course and instead choose to sign for voluntary return under the Law on Foreigners.

Where Kosovo has a bilateral agreement with another state on voluntary return of citizens, the process is more straightforward. But in the remainder of cases, external assistance is often requested.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) helps to facilitate communication with states with which Kosovo has no agreement, saying that Kosovo has only 24 such bilateral agreements on voluntary return of its citizens in place.

It was with IOM’s support that the Ministry of Internal Affairs returned two Algerian nationals to their home country on September 19 this year.

Habib Habibi, project coordinator at IOM’s Kosovo office, says the organization assisted with the communications with the Embassy of Algeria in Belgrade after two citizens from the north African state decided to sign for voluntary return.

Habibi says that Ministry of Internal Affairs officials contact IOM when immigrants have expressed an interest in voluntary return. IOM then interviews them, before the detainee signs a return statement. “We must be very careful that this statement is given without any pressure and that [the detainee] receives an explanation of the next steps, namely what [assistance] IOM provides,” Habibi says.

According to Habibi, in the case of the two Algerians, IOM assisted with a small amount of money ahead of their departure to help cover basic expenses during travel and any emergency needs in the first month after return.

If the authorities are unable to reach an agreement with the detainee’s state of origin to return them within a year, the individual must be released from the Detention Center, although they would still be irregular migrants with no residence status in Kosovo. According to the Detention Center, there have been no cases in which a person has been released in this way to date.

Valon Krasniqi, director of the Department for Citizenship, Asylum and Migration at the Ministry of the Interior, says that if after the release they are subsequently arrested, the individuals may be returned to the Detention Center.

Because the state does not provide free legal assistance in the Detention Center, these services must also be carried out by NGOs such as IOM.

Habibi says that in addition to responding reactively when the Ministry calls, IOM plans to proactively make visits, presentations and prepare leaflets to inform foreigners held in Kosovo about the possibility of their voluntary return.

In addition to IOM, the Civil Rights Program Kosovo (CRP/K) also provides limited counsel at this center.

Memli Ymeri, coordinator of the Asylum and Refugee Unit at CRP/K, says the organization is primarily interested in ascertaining whether those being held at the Detention Center should in fact be in the Asylum Seekers Center, a task that, he says, requires only a simple interview with the detainee.

Memli Ymeri from the Civil Rights Program Kosovo says his organization has little to do with the Detention Center, other than establishing whether detainees are in the correct facility. Photo: Uran Krasniqi.

However, Ymeri says that most of those being held at the Detention Center are not interested in seeking asylum and so the organization effectively no longer works with it.

A lack of monitoring organizations looking into conditions in either the Detention Center or the Asylum Seekers Center and publishing their findings makes it difficult to know the extent to which services in these centers are of sufficient quality. Only the National Preventive Mechanism Against Torture (NPM), which functions within the Ombudsperson’s Office, is able to closely monitor the treatment of foreigners in these centers at any time, and this only reports on the situation once or twice a year.

But the director of NPM, Shqipe Mala, says that the mechanism has not focused much on the observation of the asylum and detention centers. “In fact, we’ve not [even] focused much on prisons really…” she says, referring to the small number of staff at NPM and suggesting that correctional and psychiatric rehabilitation institutions face larger issues.

Shqipe Mala from the National Preventive Mechanism says there are few resources available to closely monitor Kosovo’s asylum and detention centers. Photo: Uran Krasniqi.

The media also struggles for access to the two centers. One of the most recent media interviews from someone held at the Detention Center is from 2016 when the Telegrafi portal published an article titled ‘Life Waiting to Escape From Kosovo,’ in which they interviewed a 34-year-old Iranian.

“I have no regular documents and I’m waiting for the Republic of Kosovo to give me a document so I can leave here,” said the Iranian citizen who had been caught using a false passport. In such cases, the state issues a travel document for a one-way trip to the country of origin, unless an original document is first issued by the relevant state.

“The heavy iron doors, the barbed wire and the guards in the yard, where he goes for a walk once a day, point to the limited life that he is now living in a state where he never intended to end up,” the portal described.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs rejected two K2.0 requests to visit the Center, on the grounds that the detainees have not expressed an interest in being interviewed by journalists. The responses were dated June 25 and July 25.

“Even when the Ombudsperson visits, they still do not talk,” says the Detention Center’s senior official, Nerxhivane Daka.

Niman Hajdari, a lawyer at NPM who has conducted interviews in the Center since 2016, denies this, stating that there have been no cases in which detainees have refrained from talking to them.

Lawyer Niman Hajdari says claims from the Detention Center that detainees are unwilling to be interviewed are untrue. Photo: Uran Krasniqi.

Hajdari says that during interviews at the Detention Center the primary issue is with communication because the detainees speak languages rarely found in Kosovo and need interpreters, which they are entitled to under the Law on Foreigners. In a recent visit, he illustrates, an Algerian spoke no French, and only Arabic. He says that because of such cases, NPM commissioned brochures in Arabic.

But while it is relatively straightforward to find an Arabic interpreter, other languages spoken by detainees coming from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran pose a real challenge.

For example, when CRP/K needs to communicate with someone that speaks the Urdu language, it engages Hindi speaking interpreter Gopal Singh Khadka who, together with his brother, owns The Himalayan Gurkha restaurant in Prishtina.

“These languages are similar and differ only in written form,” Khadka says.

Khadka has been living in Kosovo for 13 years, has a permanent residence permit and speaks Albanian daily. He says that predominantly, migrants who are escaping their countries, are in fact fleeing poverty.

“They often tell me they want to go to Europe for a better job,” he says.

Scant services

While external monitoring of the Detention Center and Asylum Seekers Center is far from comprehensive, it is still clear that certain services are lacking.

The Ombudsperson’s annual report for 2017 mentioned the need for an in-house doctor at the Detention Center, a standard set by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT).

“The standards established by the CPT regarding the rights of foreign detainees determine the right to have a doctor as a fundamental right and one of the guarantees against ill treatment,” the report states.

Head of the Detention Center, Selman Nimanaj, says that he has asked the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the Center to be serviced with permanent medical staff as foreseen by the Ministry’s own regulations that govern the center, which say it should have an in-house doctor. “The first week I arrived, I complained about the lack of medical staff,” he says.

An ambulance can drive from Prishtina to the Center in Vranidoll, but the capital is about 15 kilometers away.

The international organization Jesuit Refugee Service, which has operated in Kosovo in the fields of health and education since 2001, donates medical and hygiene supplies to people being held at both the Asylum Seekers Center and the Detention Center.

“We consider that it is of utmost importance to have a physician to facilitate this service,” says director of the organization Orjana Shabani. “In cases where the Detention Center needs a physician, they [currently] need to inform a QKUK in Prishtina to send medical assistance.”

Orjana Shabani’s Jesuit Refugee Council has been providing medical and hygiene supplies to those in Kosovo’s detention and asylum centers but says the centers themselves should be providing better medical care. Photo: Uran Krasniqi.

An in-house doctor should also be present at the Asylum Seekers Center — where Algerian Rabehi Lamine died earlier this year — according to its regulations. But instead, medical services for those at the Center are provided by the Family Medicine Center in Magura, which performs an initial medical examination at the point of admission.

Asylum Seekers Center statistics show that as of the beginning of August around 130 asylum seekers had undergone around 300 medical examinations this year; some cases had also been referred for follow up treatment at QKUK in Prishtina, including at its specialist departments for neurosurgery, cardiology, oncology, psychiatry, radiology and orthopedics.

According to Zariqi, the average cost per day per asylum seeker is 20 euros, while the total budget, which includes food supply, maintenance, paying the insurance company and staff salaries, amounts to about 90,000 euros.

The institutional vacuum and inadequate state procedures that fail to meet practical needs affect the lives of those being held in the centers in other forms, too.

For example, on the afternoon of October 6, 2018, a small number of asylum seekers who had recently arrived were instructed not to leave the Asylum Seekers Center as they had not not been issued with an asylum seeker identification document containing information such as name and date of birth. Such documents are only issued on Mondays to Fridays at the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ building in Prishtina.

Because it was a Sunday, and therefore the documents couldn’t be issued, they were advised to stay inside. Asylum Seekers Center director Zariqi says that the asylum seekers were advised not to spend more than 10 or 15 minutes outside since they could be arrested by the police in the absence of documents.

Ineffective procedures means that those who arrive at Kosovo’s Asylum Center outside weekday working hours are advised to stay inside until their paperwork is processed in Prishtina. Photo: Uran Krasniqi.

He says that with a new Administrative Instruction on Procedures for Applicants anticipated in the near future, asylum seekers will soon be able to “move freely in the territory of the Republic of Kosovo from the moment of their application for international protection and issuing of ID cards until a final decision is taken.”

To enable this, he says that asylum seeker ID cards are expected to be issued in the Asylum Seekers Center itself, rather than in Prishtina, and that according to the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ legislative plan, the instruction is expected to take effect by the end of 2018.

Back at the Detention Center, there are further concerns about the conditions facing those being held. The NPM says that detainees only get one or two hours of “airing” — a term used in the Center’s regulations to mean outdoor activity.

NPM lawyer Niman Hajdari says there is no program of activities for “airing” hours. “Since [the person being detained] is not charged with a criminal offense, international organizations recommend increasing activities so their detention resembles real detention as little as possible,” he says.

The standards set by CPT stipulate that the movement of irregular migrants should be limited as little as possible and that they are to have free access to physical exercise throughout the day while the premises should be equipped with equipment for sitting, resting, and so on.

Hajdari, says that the NPM has ascertained a general lack of qualification amongst staff at both the Detention Center and the Asylum Seekers Center. Security at both companies is currently outsourced by the Ministry of Internal Affairs to the Rojet e Nderit security company.

“Security officials don’t know how to behave, especially … when detainees have been isolated,” he says, referring to detainees being placed in isolation rooms for up to 48 hours. “The physician should [regularly] check on the detainee, with a check needing to be performed every 15 minutes in order to prevent potential suicide.”

He says security workers should be provided with relevant training. “They are trained to protect property and facilities,” he says. “But referring to the recommendations of the European Committee [CPT], specific training on working with specific categories [of people being held] should at least be provided… even if they are not regular police officers.”

CPT standards suggest that qualified staff “should be carefully selected” and that they should have cultural sensibility to ensure “genuine communication,” while at least some staff should have “relevant language skills.”

Valon Krasniqi says the Ministry of Internal Affairs has “expressed concern” to the Kosovo Police and has asked them to take over security at the Detention Center. However, he claims this request has not been approved by the police as they have “estimated that the level of risk is not so high.”

Kosovo Police would not confirm or deny the assessment, but responded that “reports on level of risk are given to the institutions and they decide on their publication.”

These kinds of responses seem to illustrate the state’s broader approach to dealing with often vulnerable foreigners within Kosovo — blurred and inconclusive responsibilities, a lack of effective services and treatment well below the level prescribed by international standards.K

Editing by Artan Mustafa.

Additional editing: Jack Butcher, Besa Luci.

Language editing: Lauren Peace.

Feature image: Uran Krasniqi.

This article was written as part of K2.0’s Human Rights Journalism Fellowship, 2018.

Back to monograph