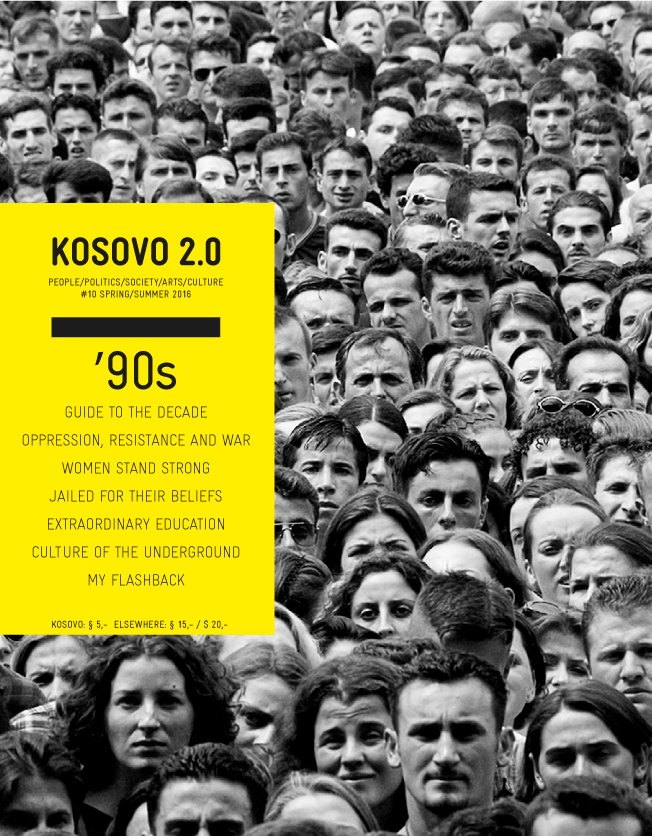

#10 '90s

“Green” confronts the grave environmental crisis facing Kosovo. This issue addresses air and water pollution, waste overproduction, deforestation and contaminated rivers. It also explores the health risks communities face from industrial activities and power plants. "Green" combines investigative journalism with an analysis of waste management, legal and social obstacles, and civic and policy solutions to argue that environmental protection is essential for achieving a healthier future.

Meanwhile, this magazine is also based on the belief that the 1990s embodied a set of values that today have largely ceased to prevail.

Kosovo 2.0

Kosovo 2.0 is a pioneering independent media organization that engages society in insightful discussion. Through our print and online magazines, debates and advocacy initiatives, we are dedicated to deepening the understanding of current affairs in Kosovo, the region and beyond.

This story was originally written in English.