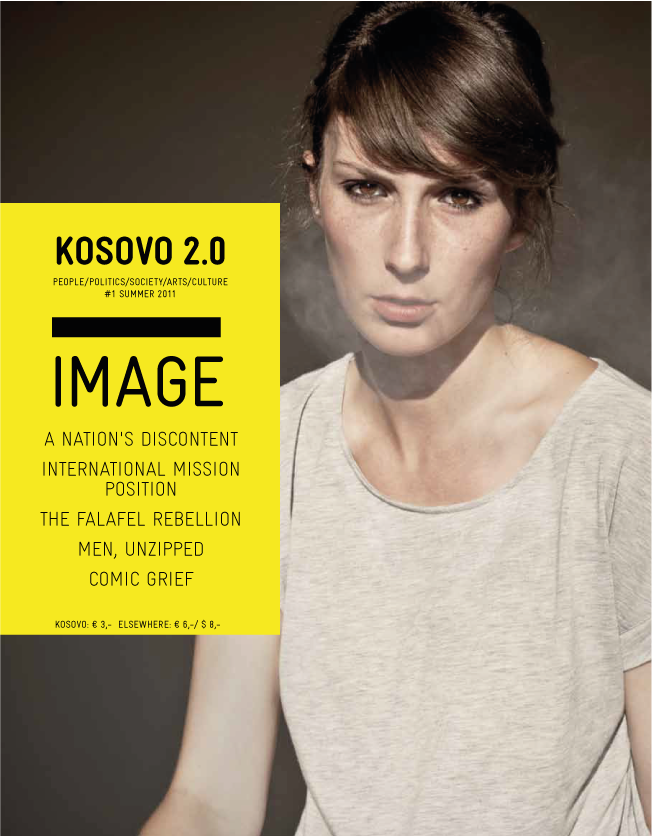

#1 IMAGE

Kosovo 2.0’s debut issue, “Image,” explores independent Kosovo post-2008 — a time crystallized by symbols like NEWBORN — that contain the promise and pressure of shaping a national image. Beyond surface-level analysis, this issue interrogates how international perceptions and local self-representations have simplified, distorted or overlooked the complexities of collective identity. Through a blend of critique and celebration, “Image” sets the tone for a magazine committed to thoughtful, nuanced storytelling.

This is no longer the Kosovo that needs to capitalize on the image shaped and transmitted by international media and politics .

Besa Luci

Besa Luci is K2.0’s editor-in-chief and co-founder. Besa has a master’s degree in journalism/magazine writing from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism in Columbia, U.S..

This story was originally written in Albanian.