In August 2019, my brother received a call saying that he was invited for a work interview at an elementary school in Fushë Kosova. The next day, we took the bus for half an hour and found ourselves in front of a white, two story building.

When we entered the premises, we saw no children. The only person there was the maintenance worker who didn’t even notice our presence.

A woman was smoking by the entrance of the building. I asked her whether the examination will be held here. For a few moments, she looked at Betim’s hand clutching my arm and answered: “Yes, yes, it will be held here.”

When we entered, the hall was full of candidates who had come to undergo the examination for the position of psychology teacher at the school.

That day, I was there to accompany my brother for the written examination, as I always do for every job that he applies for. But this time — like every other time when we informed employers about Betim’s participation in examinations — the institution did not provide a test in the Braille alphabet.

We sat in the front row so as not to bother the other candidates with my reading. They began handing out the tests. When it was our turn, I was asked to move to another desk. I told them that I was there to accompany Betim. After a 10 to 15 minute explanation, I was asked a series of questions.

“Did this man apply for a job? So, are you going to read the questions for him?” I proceeded to tell them that I was only there to write what my brother would say.

A man in his fifties asked me to show a personal and student ID. All the other candidates had begun their examination, except for Betim. Three out of the four members of the commission came very close to us and they did not let us begin taking the test until all of the questions were finished. Finally, the woman who was handing out tests also gave me the three page exam.

While I was reading the questions and Betim tried to listen, my voice would get muddled by the clanking of one of the members of the commission walking around in heels. She came near us and stayed there during the whole examination process.

Betim continued to speak and I would write. In the end, after all the papers were handed in, the member who gave me the test marked Bekim’s test with a stroke of the pencil.

The results came out two weeks later but he was not invited to the interview.

Betim Bregovina with his sister Liridona, who usually accompanies him when he applies for a job.

This kind of disregard is commonplace and it has been happening for the past three years, ever since Betim started applying for jobs. My 34-year-old brother completed his studies in psychology and pedagogy at the University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina.”

Yet, Betim is not alone in this. He is only one of many disabled people who deal with a series of institutional and state obstacles in order to become employed, and they often fail to do so.

In fact, there are no official figures for disabled people in Kosovo. The Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare (MLSW) says it has data only on the number of beneficiaries of the pension plan for people with disabilities, which is 18,450. Meanwhile, according to the World Health Organization, the number of people with disabilities in Kosovo is between 170,000 to 255,000.

According to a 2019 report by UNICEF, this lack of accurate figures occurs because in Kosovo there are many definitions of limited ability or special needs, and as a result, institutions do not have a unified definition that would help in making policies that are suitable for these groups in need.

So, like many others, my brother Betim remains an inaccurate and misunderstood number.

Opportunities on paper, exclusion in practice

Besides giving me a deeper understanding of the needs and specificities of visually-impaired individuals, living with Betim has also exposed me to all the laws, measures and documents that should ideally have an effect on guaranteeing their welfare and inclusion in society. It has also helped getting to know many members of various NGOs in Kosovo that work for the rights of people with various disabilities.

What most of these members highlight is the lack of employment opportunities, despite the fact that the Law on Vocational Ability, Rehabilitation and Employment of People with Disabilities obligates every employer — both in private and public institutions — to employ at least one disabled person for every 50 employees.

The employment rate of people with disabilities does not even reach 1%.

The lack of employment of this societal group also contradicts the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, that states, “State Parties shall take appropriate measures to enable people with disabilities to develop and utilize their creative, artistic, and intellectual potential, not only for their own benefit, but also for the enrichment of society.”

But both of these are often overlooked in Kosovo. For example, according to data obtained from MLSW, out of 347,000 persons employed in Kosovo, only about 90 of them are people with disabilities. Out of 11,287 people employed in ministries and other central government institutions (civil service), 64 are people with disabilities. Even if we refer to the ministry’s data — which includes only those people with disabilities who receive a pension — their employment rate, whether in public or private enterprises, would still not reach 1%.

But even when disabled people apply for work, often the only way they are accepted is by shedding light on the discrimination that they are subject to. Hajredin Krasniqi, who works as a telecommunications technician, has had such an experience.

Hajredin Krasniqi, who has a walking disability, managed to be employed only after a series of complaints sent to institutions and public pressure. Photo: Mrika Selimi.

On September 24, 2019 he applied at the administrative sector of the Kishnica sub-branch of the Trepça Mine. Krasniqi, who is diagnosed with coxofemoral luxation (which causes walking problems), had attached the medical decision documenting his disability to the application documents. Although he says he had passed 66% of the written test, and according to him, had also been successful in the interview, he was not included in the list of names of employees. According to him, the only result not included in this list was that of his test.

He managed to get a job there only after he lodged a complaint with the mine administration, the Human Rights Council, the Ombudsman and the Prime Minister’s Office.

But he thinks the fact that he also exerted public pressure helped his effort.

“I think that, in fact, the issue of my acceptance at work has to do with me appearing on TV while the complaints were being processed,” he told me when I spoke to him at a cafe in the Hajvalia neighborhood in Prishtina in September. “I had an interview on the issue of the lack of employment and I think that this did something for me to become employed.”

In August 2018, MLSW had also approved an Administrative Instruction on the Manner, Procedures and Deadlines for Monthly Payment for Employers who do not Employ Persons with Disabilities. This instruction obliges employers to pay the MLSW an amount equal to the minimum wage if they do not employ one person with disabilities for every 50 employees.

In September I met Afrim Maliqi from Handikos — an association known for its long-standing commitment to improving the rights and living standards of people with disabilities in Kosovo. He told me that neither the employment law for the employment of every 50th person, nor the instruction for monthly payment are enforced. For example, in 2018 Handikos conducted a survey of 26 private enterprises and found that 12 of them are not even aware of the existence of the law about the employment of people with disabilities.

Maliqi was especially critical of the Labour Inspectorate, which according to him has not monitored the application of the instruction and law. It is obligated to monitor the application of the law and act in cases when obligations are not fulfilled — including the payment of the obligation for the failure to employ people with disabilities.

Afrim Krasniqi from Handikos is critical of institutions, especially the Labour Inspectorate, for the lack of enforcement and monitoring of the law that would allow the employment of disabled people. Foto: Mrika Selimi.

The head inspector of the Labour Inspectorate (LI), Ekrem Kastrati, justified this with the fact that so far, no fines were issued for failure to apply this law, because according to him “there were no complaints from this category of citizens.”

“The IP has not received any special complaints by disabled people, and this is because of the lack of awareness of this category about their rights, while we have informed employers with over 50 employees about their obligation during regular inspections,” Kastrati told me.

However, Halil Kurmehaj did not agree with this. He is the director of the NGO Independent Initiative of Kosovo’s Blind, the only organization in the country that has been doing advocacy for the rights of the visually imparied for the past three years. Kurmehaj and I have known each other since the establishment of the organization he directs. There we requested institutional engagement for the application of the law on the employment of blind people, which brought together a small number of citizens, mostly visually impaired people and their families.

I met Kurmehaj, a lawyer by profession, at his office in Prishtina in October. He told me that in cases where it was established that there was a violation of the law or discrimination in the competition, they reacted as an organization.

“I submitted complaints and managed to annul calls for applications in the recruitment process for employment in the Assembly of Kosovo, then afterward in the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Finance. “I also partially annulled a competition in the Ombudsperson,” he told me. “But it usually ended with that, cancelling the call, and not with hiring people with visual impairments.”

The law provides not only penalties, but also rewards in case of its implementation by employers, who would benefit from a range of relief and financial benefits. For example, in addition to customs and tax benefits, employers may also receive cash incentives, which are determined on the basis of the amount of the mandatory salary contribution.

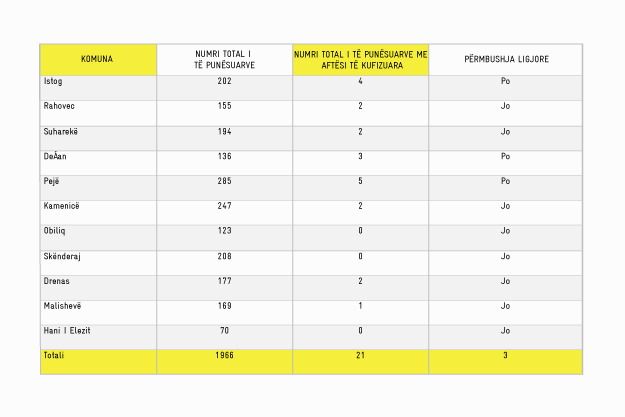

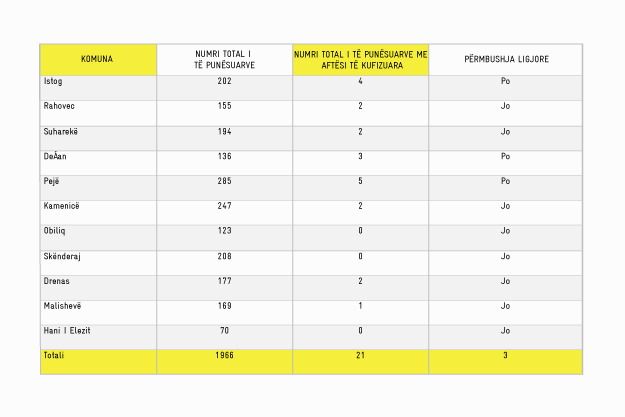

But despite all this — whether punishments or rewards — very few people with disabilities are employed, in public or private institutions. For example, out of 28 municipalities that I have contacted (out of 38 in total), only 10 of them employ people with disabilities and only one has met the minimum quota.

The table includes data on the degree that Kosovo’s municipalities are applying the Law on Vocational Ability, Rehabilitation and Employment of People with Disabilities, which stipulates that every 50th employee has to be a disabled person. Out of the 28 municipalities contacted, only 11 responded with data included in this table.

Discriminatory infrastructure

I was walking with Betim on the sidewalks of the Aktash neighborhood in Prishtina and for the first time he used his stick freely. “Let go of my arm, can’t you see, I can walk on this part myself,” he told me. People around were watching us, as it might have been the first time they saw a blind man with a stick in the streets of Prishtina.

“Now I can go to university without any problems, only with my stick. Dona, you can’t even imagine how much this sidewalk makes our lives easier,” Betim told me. During his studies, he was able to go to university only when accompanied by someone else, so the installation of this infrastructure translates into added independence for him and other blind people.

This infrastructure improvement in Prishtina was done this year, where a part of the sidewalk has been reconstructed, fulfilling the conditions for the independent movement of blind people through the establishment of uninterrupted tactile paving. But such sidewalks are limited to Prishtina and Prizren. In August of this year, Betim asked the municipality of Obiliq — where we live — to provide infrastructure for blind people in the square that was under construction. But his request was not considered.

Also, most cities in Kosovo lack acoustic traffic lights and fully accessible wheelchair infrastructure.

In the Assembly, there are still no tactile floor markers or acoustic guides for the blind.

A study conducted by Handikos in 2019, which analyzed 394 public institutions’ facilities in 30 Kosovo municipalities, shows that most of them are only partially accessible or completely inaccessible to people with disabilities. These facilities include schools, hospitals and banks, and as such are vital for people with disabilities in order for them to integrate into society.

The Assembly of Kosovo building is similar, where until 2020 there was no infrastructure that enabled the movement of people from this social group.

On December 3, 2020, 11 months after Fetah Rudi became a deputy, the infrastructure was created for people who need to move in a wheelchair, putting into operation an elevator that allows them to move independently. But in the Assembly there are still no tactile floor markers or acoustic guides for the blind, thus hindering the physical access of visually impaired people to this institution.

***

It was noon and Prizren’s traffic was absolute chaos. I was waiting in front of a shop in the Lakuriët neighborhood. From the distance I spotted Resmije Rrahmani, head of the Organization for the Rights of Persons with Muscular Dystrophy, coming toward me in an electric wheelchair. Although the streets of this neighborhood are wheelchair accessible, cars parked on the sidewalk made it difficult for her to move. But unlike this neighborhood, many roads in Prizren continue to be inaccessible to people in wheelchairs.

After we said goodbye, Rrahman took me to the office of the organization she leads.

She has worked for 20 years as a volunteer in various organizations for the rights of people with disabilities, as well as in private companies and public institutions — but none of this experience has led her to a job.

“I have never asked to do work I cannot handle, as well as a job where I don’t do any work and just get a salary,” she told me. “I have always wanted a job that I could carry out, to accomplish workplace tasks and feel accomplished.”

In 2018, Resmije Rrahmani founded the Organization for the Rights of Persons with Muscular Dystrophy; where she has continued to voluntarily advocate against discrimination in employment, which she has experienced herself. Photo: Mrika Selimi.

She founded the organization she leads in 2008 and since then has continued to work voluntarily.

“Despite my physical condition I cannot stop; I want to work, even voluntarily, like I have done for these 20 years,” he told me. “Since we are not offered the opportunity to work, I continue, trying to create a job myself.”

According to Rrahmani, the lack of employment not only makes economic independence impossible for people with disabilities, but also has a significant impact from the psychological aspect.

“People feel worthless, because if you constantly apply or even work voluntarily and the employer sees your capacity, but does not hire you because of the disability, it is really very discouraging,” she told me. “Then you start to think of yourself as useless, you even start to believe that you are not even capable of doing the job for which you are qualified.”

She also mentions the lack of infrastructure and says that even if people with disabilities are employed, a significant part of the institutions have inadequate infrastructure for them.

Refusing to surrender and making an effort amid injustice

The first alarm on the phone rang at 6 a.m. Fearing that I wouldn’t wake up, I set two alarms and wrote “Betim’s job application” as the description. We had prepared everything so that we wouldn’t miss the 7:30 a.m. bus.

Betim once again applied for a job as a school psychologist. This time, it was 89 kilometers away toward Peja, where he had completed part of his education. The job opening was at the Resource Center for Learning and Counseling for Blind or Visually Impaired Children “Xheladin Deda,” the only institution for the education of blind children.

At the station, on platform number 1, the bus was waiting for us.

Betim sat by the window. He spent eight years of his life at that school — he knew the way so well that there was no need for me to tell him how long it would take. We all wore masks on the bus, except for the conductor who came to pick up the money after the bus departed.

As we approached the station, Betim was going over the theory of psychology, administrative instructions, and other such things. When we arrived in Peja, we sat down to eat at the restaurant where he had eaten many times while he was a student. Even during the meal we could not fail to mention the issue of the examination.

“I don’t know Dona, although I always read and prepare before the tests, I never feel that I read enough. This is how I felt at university, even when I got a grade of 10,” he told me. “12 years, five months and four days after the Matura test, I am coming to school again for a test, but in a completely different way. “Today I am taking the test not to finish school, but maybe to come back here.”

Together with the other five candidates — none of whom had disabilities — we waited for the start of the examination in the teachers’ hall.

All the incoming and outgoing teachers greeted the candidates, but they greeted Betim differently; despite measures against COVID-19, some greeted him by shaking his hand. Most of them had been his teachers before.

After about half an hour, the director of the institution led us together with the other candidates to the classroom where the test was held, but Betim was put in a separate classroom. It was the first time something like this had happened. As if that were not enough, the evaluation committee had decided that I should not accompany him. He was accompanied by one of the center’s lecturers, who was a computer science teacher.

Two days later, the results came in and Betim was among the three candidates invited for an interview.

Whenever Betim had to take a written exam for a job, I accompanied him and no institution has prevented me from doing it. Betim takes more time to complete tests, and every institution understands this. But this did not happen with the resource center in Peja.

Even before the test was completed, the school principal came and asked the commission members to take the test back from Betim because the 45-minute exam time was up. He continued to put pressure on him. “You are declaring that you can do the job like everyone else, and the test must be completed like all the other candidates. If you, Betim, go to work, you have to work eight hours like everyone else, not 12,” he told him. Despite the constant pressure, Betim managed to complete the test.

Two days later, the results came in and he was among the three candidates invited for an interview.

We took the same bus to Peja once again, at the same time and with the same conductor who came for the tickets without a mask.

A man in his fifties who was sitting in front of us had overheard our conversation and started talking to Betim. He was a biology teacher in the village of Kijevë, Malisheva. “I know they will not hire me, because this is not the first time I am applying,” Betim told me. The guy shrugged, pursed his lips in regret, and said a few words of comfort.

Betim spent about 30 minutes inside the classroom where the interview took place. When he came out he was tired and asked me to leave immediately for Prishtina. He said no word on what happened within that classroom. On the way back he spoke only twice: Once he asked me what time it was and once for a bottle of water.

During years of rejection for 15 different jobs, Betim has not been discouraged nor has he given up the pursuit of his intention to serve in the psychology field. After initially completing his bachelor’s degree in general psychology, he also completed undergraduate studies in pedagogy; then went on to pursue a master’s degree in school psychology and counseling and another master’s degree in theoretical-scientific pedagogy, which he is currently pursuing.

Thanks to this unstoppable academic commitment, he can be considered overqualified for most of the positions that he has applied for, but overqualification has never been mentioned as a reason for his rejection.

There is no easy way to give bad news. And as we walked further into the courtyard, where the two of us were practically alone, I told him that he was still not hired.

Betim stopped for a few seconds. “Buka me helm më doli,” (I had hope but then it was poisoned) he told me. And he started walking again, without stopping. Knowing my brother’s insistence, I know that he will never surrender, despite the rejections, and despite the discrimination.K

Feature image: Mrika Selimi.

This publication is part of the third cycle of the Human Rights Journalism Fellowship Program, supported by the European Union Office in Kosovo. The program is co-supported by the National Endowment for Democracy. This program is being implemented by Kosovo 2.0, in partnership with Kosovar Center for Gender Studies (KCGS), and Center for Equality and Liberty (CEL). Its contents are the sole responsibility of Kosovo 2.0 and do not necessarily reflect the views of the donors.