Little brother's watching you

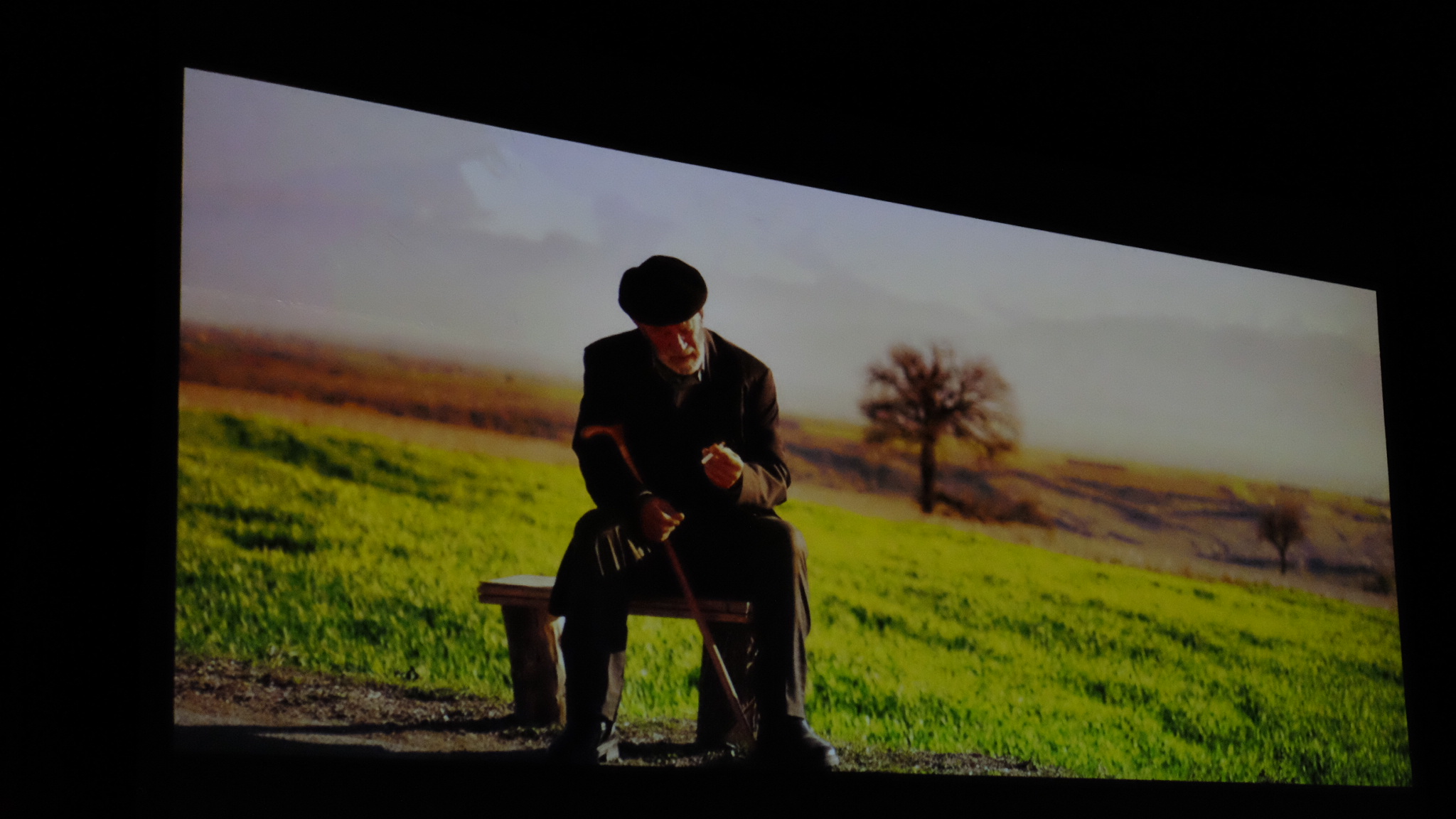

Watching your brother's film in the heart of Prishtina.

The story, an elaborate joke, feels like an experience at an intersection of a Kosovar road-crossing.

There she was, proud of her son, while keeping away the tears and the memories of what actually happened in that house.

Hasan Rrahmani

Hasan Rrahmani is a journalist on The Listening Post programme at Al Jazeera English.

This story was originally written in English.