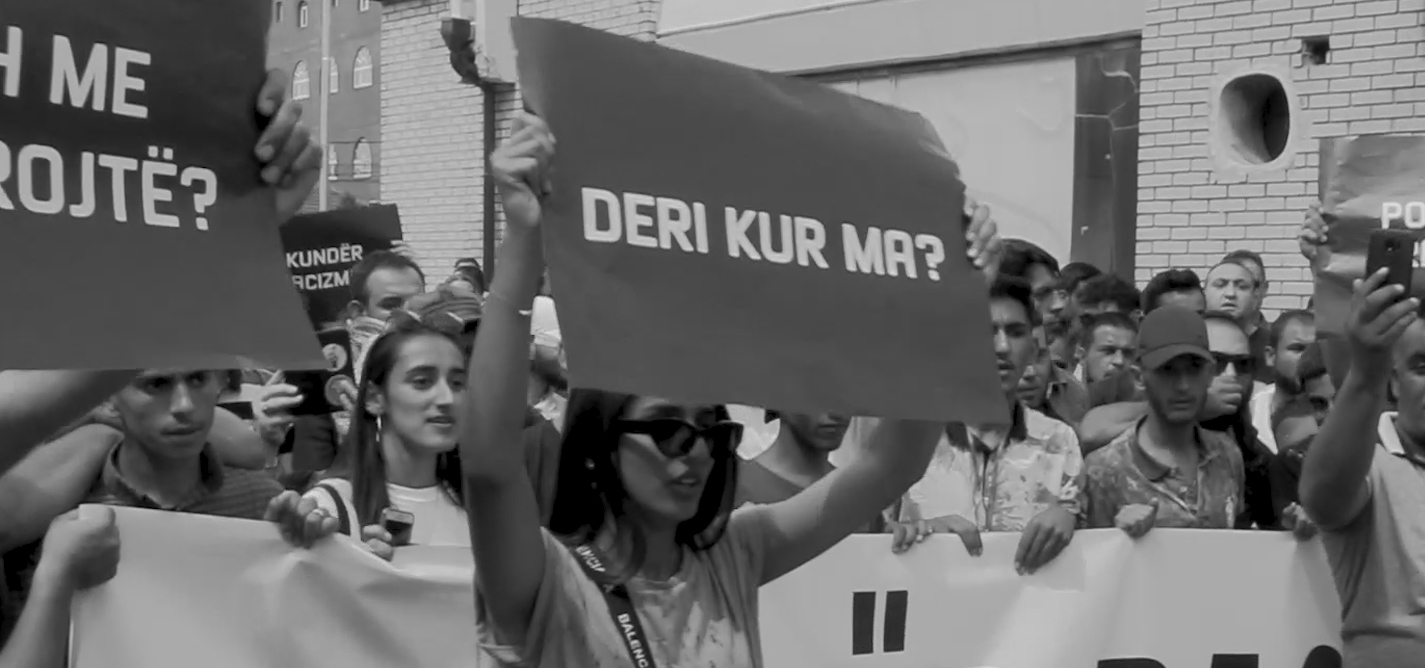

Living in the corner: Minorities within minorities

Between racism on the one hand and transphobia on the other.

She quit school in the fifth grade.

When she became an employee at one of the city's supermarkets a few weeks ago, she was told not to come back at the end of the first day of work.

“One of our challenges is to understand identities and different forms of oppression — all of them are interconnected."

Mirishahe Syla, gender expert

Dafina Halili

Dafina Halili is a senior journalist at K2.0, covering mainly human rights and social justice issues. Dafina has a master’s degree in diversity and the media from the University of Westminster in London, U.K..

This story was originally written in Albanian.