The snakelike bridge passes through the Gorge of Kaçanik. Supported by massive pillars up to 78 meters tall, its gray concrete body overshadows the previously prominent Lepenci River, which now winds its way through the bridge’s foundations. After the 2019 opening of the Arbën Xhaferi highway, which connects Kosovo with North Macedonia, the valley echoes with the noise of speeding vehicles. With a length of nearly six kilometers, the bridge is the crowning jewel of the highway, granting Kosovo the trophy of the longest bridge in the region.

For more than a decade, highways have come to signify the ultimate progress and development of the country. Inaugurated under fireworks and praised as “the Kosovo we wanted in our dreams,” they have been at the center of a grand narrative of success that consecutive governments have tried to sell to the public, a narrative that legitimized enormous government expenditures.

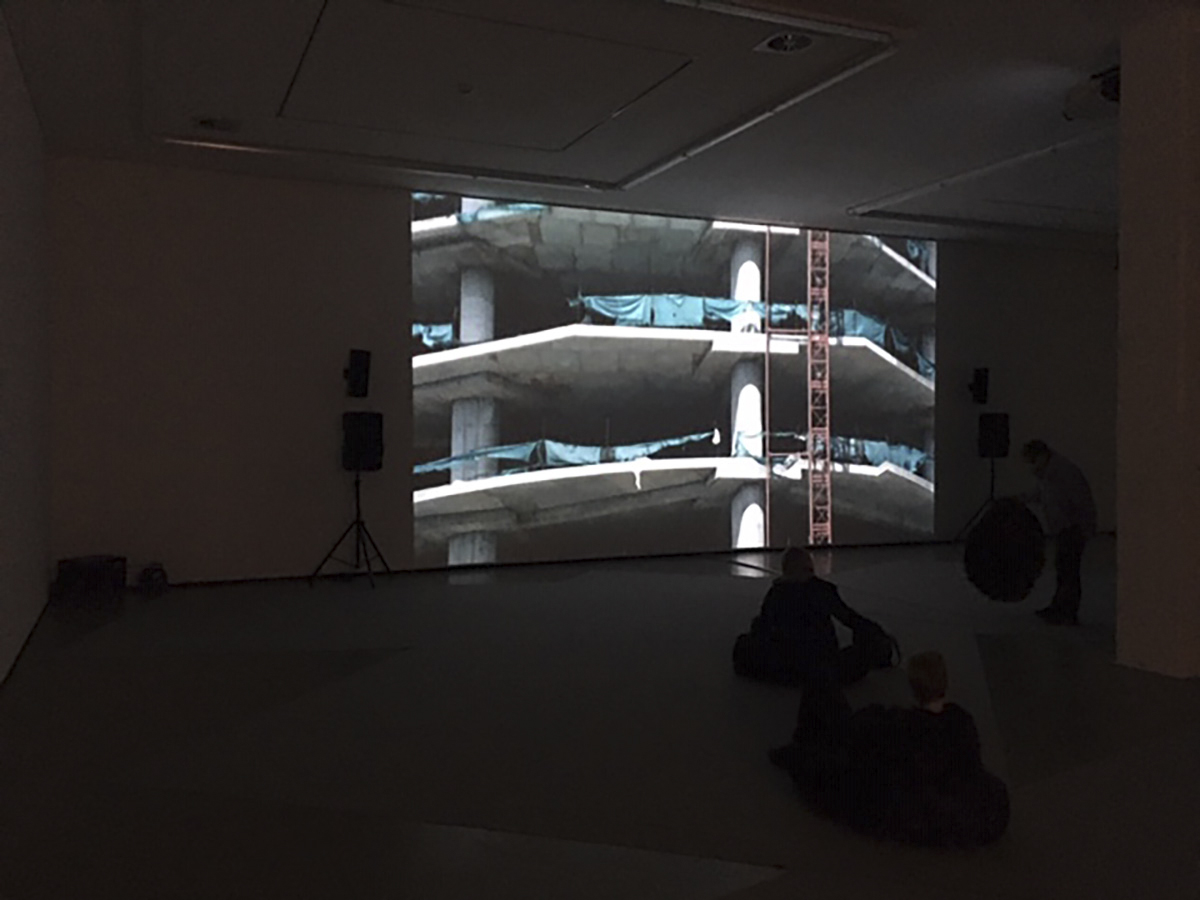

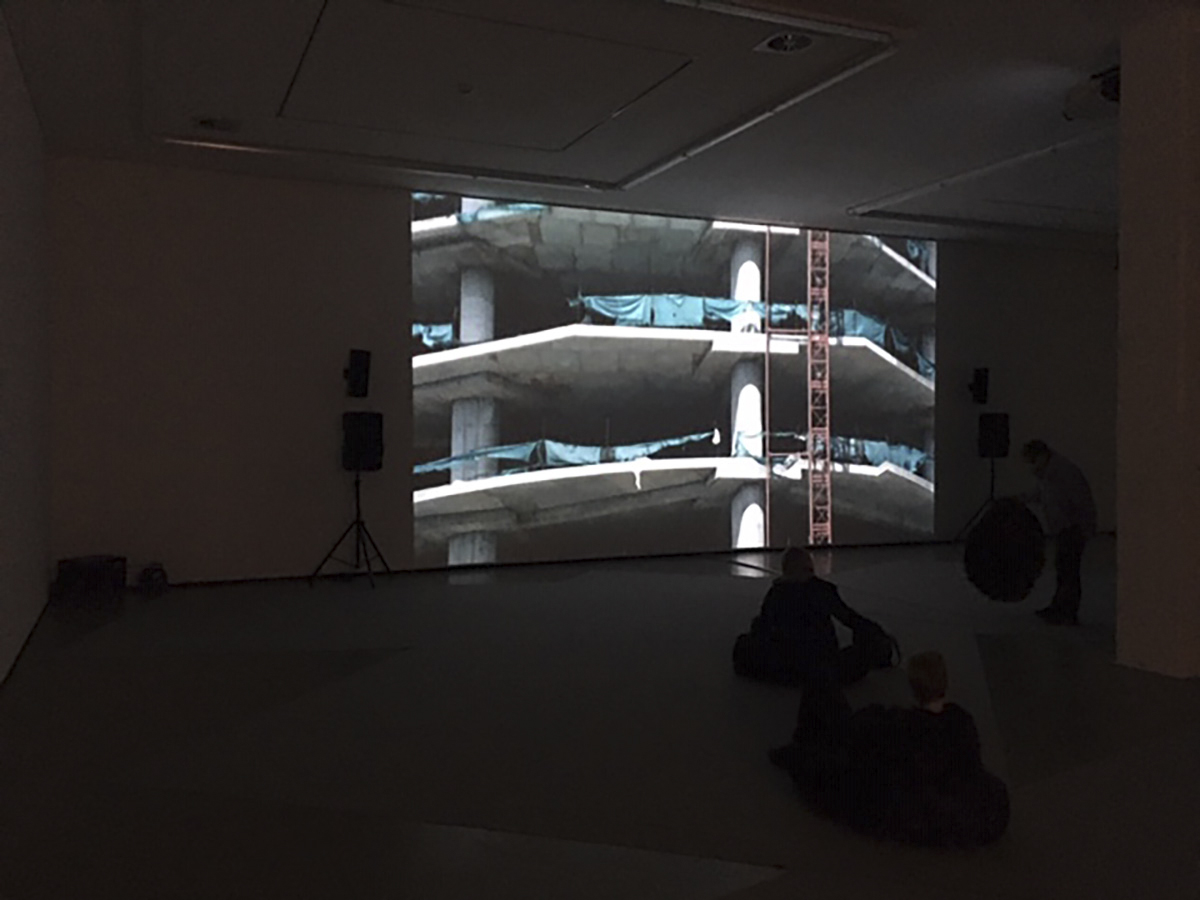

Doruntina Kastrati’s short film “When it left, death didn’t even close our eyes” counters this dominant way of thinking about progress. It tells another story, another truth, as narrated by construction workers who build the country’s roads, bridges and buildings. Centered around their testimonies about unemployment, inhumane working conditions and exploitation, the film critiques the state’s persistent negligence towards working rights violations in the construction industry.

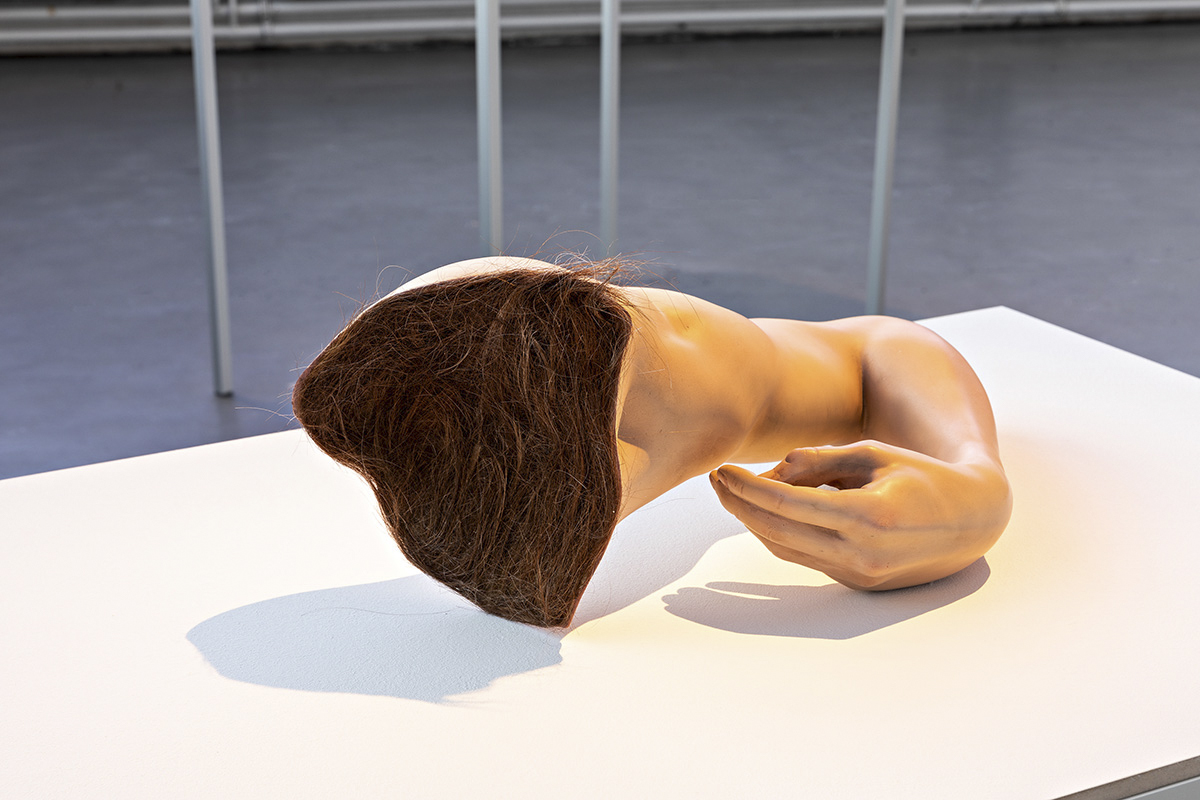

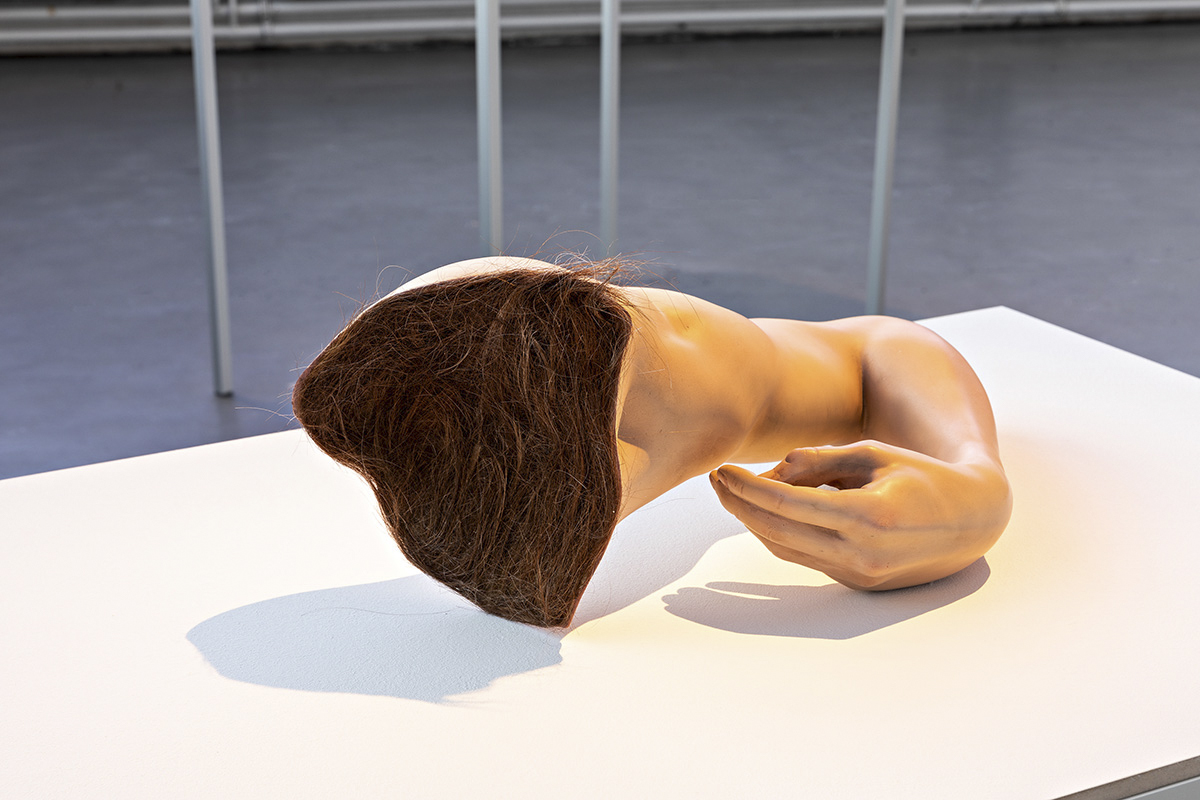

Kastrati, who primarily considers herself a research-based artist and sculptor, researched the topic for around three years, looking closely at institutional statistics, NGO reports and labor unions’ statements while conducting numerous interviews with construction workers on the ground. The film was initially presented at the National Museum of Kosovo in July 2020 as part of the exhibition “Public Heroes and Secrets,” curated by Hana Halilaj, a co-researcher on the project. The exhibition included 3D-printed sculptures of human arms, legs and backs, which index the traumatic injuries workers have received on the job.

3D-printed body parts index traumatic injuries workers have received on the job. Photo: Fred Dott.

One of the workers in the film is Enes Shehu, who as a 17-year-old started working in the construction industry. At 21 he got injured while working on the Arbën Xhaferi highway. He was then out of a job and the construction consortium in charge, Bechtel-Enka, provided no compensation.

Another worker in the film says, “I fell from the scaffolding from the 10th floor to the ground. Here is the scar I have. I was in a coma for three months. I am happy I survived. I was dead. Dead!”

Through these narratives, the film presents the bodies of workers not just as assemblages of limbs and organs but as historically formed corporealities that bear the weight of a systemic violence that too often goes unseen.

An awardee of the Young Visual Artist Award from the National Gallery of Kosovo in 2014, and the Hajde x 6 Award from the Hajde Foundation in 2017, in her previous works, Kastrati has mainly focused on the concept of public space, using her artistic installations to ask questions about illegal construction, the privatization process, people’s movement and survival. She has presented numerous solo exhibitions throughout Europe and the region. This year’s edition of Dokufest marks her film festival debut.

K2.0 met with Kastrati to talk about workers’ rights violations, privatization, the film screening at Dokufest and her next artistic projects.

K2.0: The film is shot in a very spontaneous way, and the whole story is built upon workers’ testimonies. It seems that you didn’t have a script at all.

Doruntina Kastrati: Yes, I didn’t work with a script. It’s a sensitive topic that deals with a strata of people who are exposed all the time in the streets, in places where they are really in danger. Most of these construction workers don’t have any protective equipment. If you take the time to look around, you notice they are hyper-exposed but at the same time quite invisible. You see them on the twelfth floor where they can potentially fall and die, but this has all become a routine scene. Even responsible authorities — the labor inspectorate, the police, or any other institution — have the mindset, “We’re used to all this; nothing will happen to them!”

When we began shooting, my friends Leart and Hana — and I — decided to go and see what we could find. I had the idea more or less in my head, and we had already discussed together that we were looking for something spontaneous. The film doesn’t have standard camerawork; you can discern that we shot it from different angles, except when we interviewed people who spoke about their experiences with the Bechtel-Enka [consortium]. But in the scenes where the workers are in the streets, one can see that everything is moving; there was no script at all for that. We may say that the film is a docudrama that deals directly with a human rights issue.

Most of the time, we get to hear about construction workers’ experiences only through brief media reporting, where they are represented merely as statistics — numbers of accidents, injuries and deaths. But their stories, as articulated and narrated by themselves, are rarely heard. Do you see the film as a sort of critical intervention in the public discourse around this issue?

Yes, indeed. I think it’s a strong weapon to depict a reality beyond what we get to see in the media. When I started the research, I began by looking at the statistics; I was interested in looking closely at what the labor inspectorate, labor unions, civil society organizations that work in this field and the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare had to say. I involved all these actors in the research.

But what really mattered for me were the workers’ stories. There are institutional officials who work with these statistics and have never visited construction workers to ask them about their lived realities. When we talked with the workers, they told us about cases that have never been reported. For example, those who worked for a long time for Bechtel-Enka said that there were cases when their colleagues got injured or even died that went unreported. So, then you start to question how accurate those statistics are. The film really tries to touch the working-class reality beyond mere statistics.

A sculpture from Kastrati’s exhibition “Public Heroes and Secrets.” Photo: Genta Pallaska.

The film revolves around the subject of the worker in a time when there is a tendency to say that the working class, in the classical sense of the word, no longer exists, and when its experiences are quite depoliticized.

Well, I don’t agree with this position. As long as there is a capitalist system, this cannot be the case. I have worked with different organizations in the field, and I can say that I know well the economic conditions in Kosovo; there are people who live with a salary of 150 euros per month. I, personally, come from a family where my grandparents were part of the working-class — people who worked the land or worked in factories.

Some of the workers said that if you die while building the "Nation's Highway," you'll be considered a hero since you contributed to the unification of Kosovo with Albania.

And I think that we should discuss more than ever about the figure of the worker now, during this pandemic time. We have seen that not all people have been privileged to work from home. The most endangered ones have been those doing the essential work. So, I think that this is precisely the moment when we need to go back to the subject of the worker.

Actually, the film is being screened at Dokufest in a period when more public discussion is going on about the implications of the privatization process in the past 20 years in Kosovo, and when we’re sort of witnessing more demands for a minimum wage increase. Do you see these issues as part of the film as well?

I come from Prizren, and there were factories where my grandmother and my mother used to work that no longer exist. Once, those factories were essential to the economy of many households and now, after their privatization, there are restaurants, tall buildings, etc. The way the privatization process happened in Kosovo is definitely not a good example. So, yes, the film unavoidably touches upon these issues as well.

The workers narrate their stories in quite personal tones. They mostly speak about bodily injuries, daily struggles to make ends meet and inhumane working conditions. But at the same time, they manifest a kind of social anger and general dissatisfaction toward state institutions and construction companies. Did you intend to look into these aspects, or were they spontaneously brought up in conversations with the workers?

I was interested in different aspects of the institutions’ work from the beginning of the research process. And then inevitably, the issue of Bechtel-Enka surfaced when I was looking at workers’ experiences in the construction industry. Some of the workers said there were thoughts among them that if you die while building the “Nation’s Highway” [Ibrahim Rugova Highway], you’ll be considered a hero since you contributed to the unification of Kosovo with Albania. It was this level of brainwashing…

… romanticizing the exploitation through nationalist narratives.

Yes! All while they got exploited by a Turkish-American company that paid a Kosovar worker 50 cents while a Turkish one who came from Turkey got 5 euros per hour. And this whole situation was immensely romanticized.

I am questioning the idea of what it means to be a hero in post-war Kosovo and how romanticizing the nation justifies the exploitation of workers.

Then, by interviewing many workers, I went from one piece of information to another, and this way, the whole research developed. Each day in the field was challenging. There were days when we would go [to meet the workers], and they would refuse to talk. But the main idea was to have the workers as the main protagonists of the narrative. We would just start shooting and let them speak uninterrupted, and sometimes pose some questions, as you can notice in the film.

I intentionally chose to present the film in the National Museum of Kosovo. The museum’s space is constructed as a place of heroes. There you mostly have personalities centered around the idea of protecting the nation, such as Adem Jashari, Ibrahim Rugova, Anton Çetta. I’m not questioning their contributions; I am questioning the very idea of what it means to be a hero in post-war Kosovo and how romanticizing the concept of the nation in the “Nation’s Highway” project actually justified the exploitation of workers.

How did the workers receive you during the research process and film shooting?

First, they thought we were the media and said, “Don’t show us on television.” But I always use consent forms in my work to clearly explain my projects to the participants. And after spending time with them, smoking one or two cigarettes together, and talking through the film idea, they understood what we wanted to do and were open to be part of it.

Most of them then said, “Screen us anywhere; we want people to hear what we have to say.” They would also ask if we could find them a job, everyone was dealing with their own hardships. We paid the workers 50 euros per interview — that’s how much we could afford with the budget we had.

They congregate at places like Bill Clinton Boulevard of the Llapi Mosque, waiting to be hired as day laborers for 5 to 10 euros per day, and we didn’t want to make them potentially lose a working day while talking to us. They didn’t even want to get compensated for the interviews; it seemed too much for them.

Sometimes when I pass by that way, they say to me, “Is there any other film you’re working on?” I invited them to the opening of the exhibition, and two of them came. Some of them couldn’t come because they’re not necessarily from Prishtina. So they were hesitant initially, but then were quite willing to talk after I met them two or three times.

From a screening of Kastrati’s documentary “When it left, death didn’t even close our eyes.” Photo: Fred Dott.

At some point in the film, while talking to one of the workers, you ask him, “Do you know there are labor unions? Have you ever reached out to them?” This moment, and workers’ testimonies throughout the film, made me think about class consciousness, the ability to critically question existing socio-economic relations and one’s own position within that hierarchy. Do you think the film has the power to raise class consciousness?

Art has this power, and I think it needs to have it. After finalizing the film, we tried to help the workers report the violations [of their rights]. We gave them some administrative information about reporting procedures. Two cases have been reported. One of the workers, Ilir, has filed the case in court.

But some of the services are costly, and most of these workers can’t afford them. And they’ve lost their hope; they have no more hope that their country, Kosovo, can work in their favor.

As a film team, we’ve thought of offering free aid to the workers about reporting steps. We managed to send just one case to the court, but I think the other workers have become a bit more aware that there is a labor union. But whether the union does enough in this regard is also a question we have to ask.

Workers' colleagues got injured or died in the workplace and no one talked about it.

In your previous works, one of the issues you’ve dealt with is illegal construction. When watching the film, one can see that these huge monstrous building sites occupy most of the film’s scenes. Is this a continuation of your artistic interventions in this topic?

Yes, I think this topic is part of the film. The work I’ve been doing for ten years around this issue has become an intrinsic part of all my research processes. I’ve done interventions about this topic in Prizren and the region — in Albania and Greece. It’s almost the same problem around the Balkans. This film somehow fuses all the previous topics I’ve worked on throughout the years.

The film’s title comes from a verse of Roberto Bolaño’s poem “Godzilla in Mexico.” Why did you choose this poem, and particularly this verse, as the film’s title?

The exhibition’s title “Public heroes and secrets” is a verse from Roberto Bolaño’s poem “Godzilla in Mexico.” In the poem, he talks with his son about a catastrophe that they somehow manage to survive. Bolaño is one of my favorite writers. When I was thinking about the exhibition’s title, for me, “public heroes” meant these working people whom we see every day but no one talks about, and then the “secrets” that these public heroes carry within themselves — the things they tell about Bechtel-Enka, how their colleagues got injured or died in the workplace and no one talked about it.

And, the film’s title also, “When it left, death didn’t even close our eyes,” is a verse from the same poem that talks about the experiences, in this case, of workers who after accidents understand that death was potentially there, but that it just wasn’t the moment to close their eyes. It’s a constant circle. Death is all the time among us; we just don’t know how, when…

This is one of my favorite poems and it has been with me for years. I’ve always thought that its verses could potentially be titles of my works. And, this was the right moment to do that.

Initially, the film was screened as part of the exhibition. Do you think that now, after its screening in Dokufest, the film will have more of a journey on its own, independent from the exhibition?

I’ve already screened the film in different places in Europe, and it has been received pretty well. I think the sculptures are an inseparable part of the whole project, but also each of the parts — the sculptures and the film — has its own presence whether presented together or separately. So far, the film has been screened in Hamburg, Berlin, Albania, France, but never in a film festival.

So, it’s the first time it will be part of a film festival program, and I don’t know what its journey will be like after this. I am quite excited that it will be screened in Prizren since I was born and grew up there. I’ve always been just a visitor of Dokufest, so the fact that the film will be presented in the 20th edition of the festival, it’s a feeling I’ve never experienced before. It makes me feel really good.

I am already working on another film that also deals with workers’ experiences. It looks at a factory of women workers where my mother used to work, and it mainly focuses on working-class women’s labor. I am planning to finalize it by 2022.

Will it also be a short film?

Yes! I think for now this format allows me to say what I want to say. In the future, I don’t know…

Does this mean that you’ll continue with filmmaking?

I love cinema and watching films, and especially in recent years I’ve had a closer relationship with it. But this does not make me a film director. I consider myself a sculptor because my work takes form and breathes in this medium, and every other medium incorporated in my artistic work is an additional element.

This article has been edited for length and clarity. The conversation was conducted in Albanian.

Feature image: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0