There is no greater agony, said Maya Angelou, than bearing an untold story inside of you. For Paul Conroy, an experienced photographer in war zones, the mayhem of war is a place where an untold personal story is perhaps the one cathartic channel out to the world — and telling it is the only vague hope left in those who suffer the bloodshed that it was not all in vain. In Syria, Conroy lived through that mayhem first hand.

Twenty years after the war in Kosovo, which was his first ever conflict as a photographer, Conroy returned earlier this month as a guest of this year’s edition of DokuFest, for the screening of the documentary “Under the wire.”

The thriller-like documentary puts Conroy on the other side of the story — as the protagonist, rather than the storyteller — and chronicles his difficult time in the sieged Syrian city of Homs in 2012. It also tells the story of his partner, late veteran and celebrated American war correspondent Marie Colvin.

Remembered by many as the journalist with the patch on one eye, an image that undoubtedly made her look just as tough as she was, Marie Colvin’s death in Homs under the bombing of Bashar al-Assad’s government was a heartbreaking reminder that the Syrian war didn’t want witnesses — especially any as fearless as Colvin, and her partner behind the camera, Conroy.

Experienced reporters for The Sunday Times of London, the pair had made a name in past conflicts, including the Kosovo war. Colvin will be remembered as a committed journalist, determined to bear witness and tell the story of those suffering the attacks of power.

Conroy, who spent six years in the Royal Artillery and experienced war from another angle while posted at the German border during the Cold War, found himself a kindred spirit in Colvin. The two entered Syria illegally, and reached the deadly city of Homs, which was sieged between 2011 and 2014. From there, they extensively reported on the deliberate attacks on civilians by the forces of Bashar al-Assad, for a while as the only western journalists in the city.

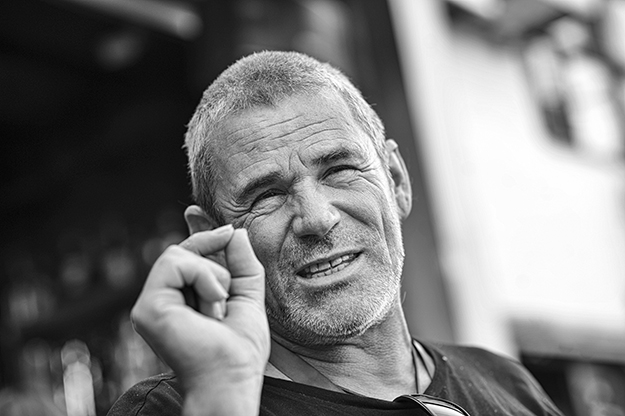

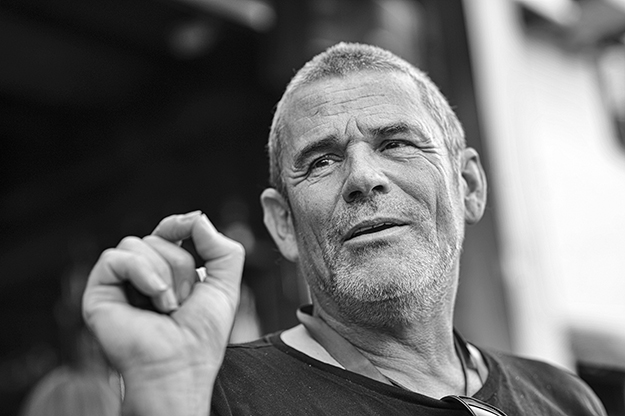

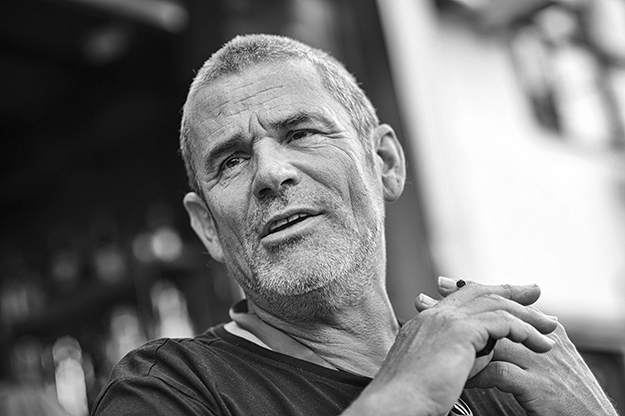

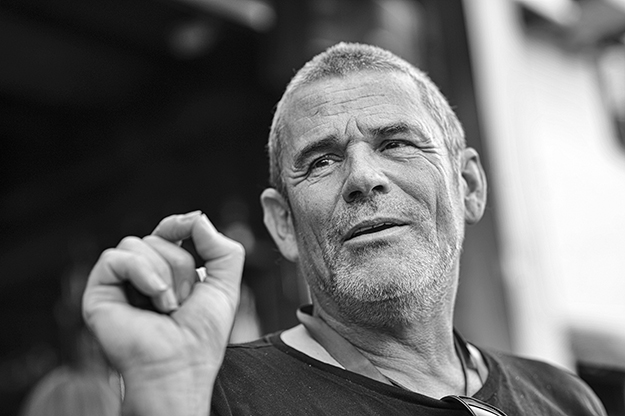

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

In February 2012, Colvin and French photographer Remi Ochlik died, after the temporary media center in the rebel-held district of Baba Amr was shelled. Conroy and French journalist Edith Bouvier were among those injured in the same attack, though they were miraculously evacuated days later in an operation carried out with the support of Syrian activists. In 2016, Colvin’s family filed a suit against the government of Bashar al-Assad, arguing that they had evidence of the attack against the journalist being deliberate.

“Under the wire,” based on a book written by Conroy about his experiences in Syria, is a documentary that combines footage taken by Conroy from the ground itself, found footage, recreated images, and interviews with the protagonists of the story. While a Hollywood feature production is in the pipeline, Martin’s documentary gives the viewer a rare glimpse of the raw circumstances in which war journalists work.

Responding to frequent questions from the audience during the two screenings at DokuFest regarding the value of war zone journalism in the 24/7 news-cycle era, Conroy insists that now more than ever war reporting is necessary, given the amount of fake news and unverified stories present in our newsfeeds. Bearing witness to the suffering of civilians is, like his former colleague Colvin, his motto.

After the attack, in which Conroy’s leg was badly injured, the photographer has not returned to conflict zones. Not only because there is a death sentence placed on his head for his reporting in Syria, but also because he is not yet physically fit for conflict reporting.

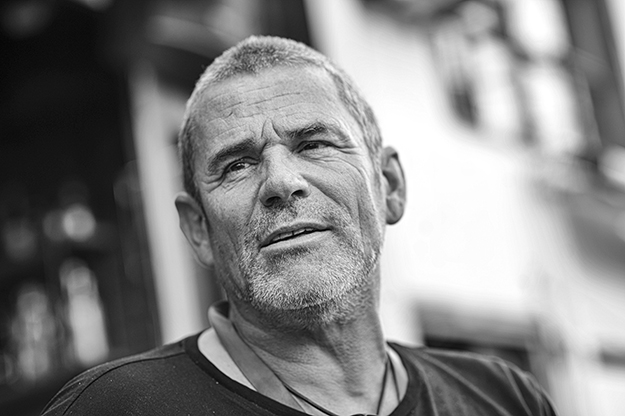

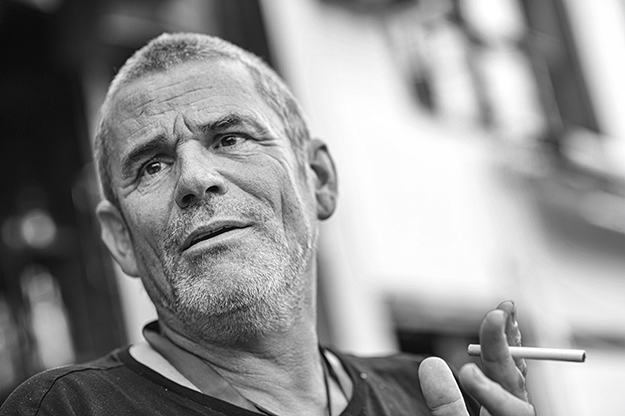

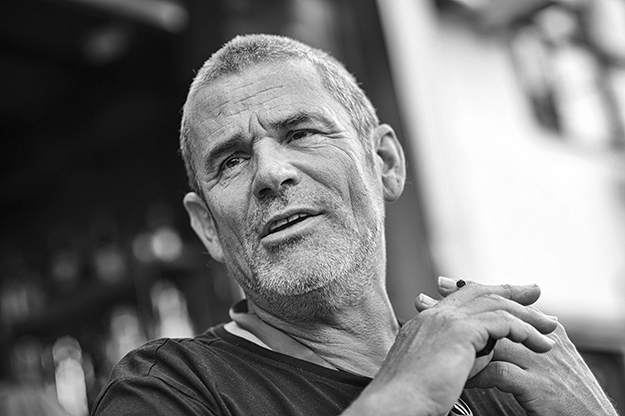

K2.0 sat down with Conroy during a quiet afternoon in Prizren to talk about the struggles of doing journalism in the midst of war, and the meaning of photography and journalism in the era of the democratization of the media.

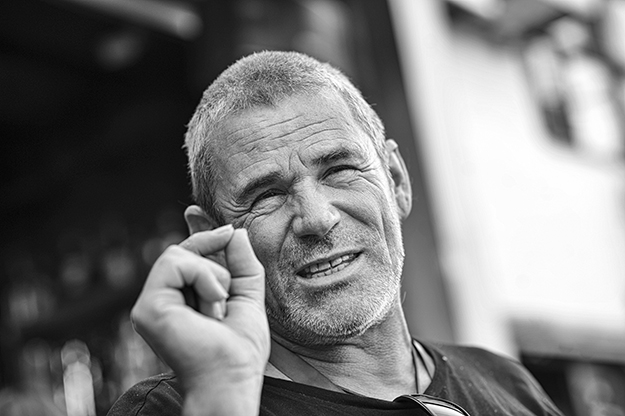

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

K2.0: What drove you to photography in the very beginning?

Paul Conroy: I loved photography from the moment the very first video-cameras were showing up — those little disposable cameras, or the Blackmagic. I didn’t get started as a photographer though, I became a soldier when I was 16. I spent six years in the army, and when I came out I was like: ‘What do you do with that?’ I didn’t feel very qualified. I had learned to kill people, basically. I felt like I’d wasted six years.

After the army I played music and got into the recording studios in Liverpool. I was in the studio once and I got a call from a friend that says: ‘Paul, we’re going down to the Balkans, we’re taking an aid convoy to Kosovo.’ He asked whether I would go with them and photograph or maybe film.

We drove to Albania with seven lorries of aid and dropped it in Kukës. I took pictures and filmed, and they said: ‘time to go home…’ I was like: ‘I’m not going home, I’m staying.’

I stayed in Kukës and met up with the UÇK [Kosovo Liberation Army]. They were going into Kosovo and I said: ‘I’m going into Kosovo with you.’ That was beginning of ‘99. I stayed for about six months, until Prizren was liberated.

I drove into Prizren with the German Army and the UÇK. It was fantastic. We drove down the high streets and it was like proper liberation. For some it was the first time they’d left their houses [in a long time]. They put on their dresses and they were throwing flowers to all the cars.

I was with a Danish journalist and we drove down the high street and we were like: ‘Wow! This is like Paris after the war!’ It was a proper liberation, with all the flowers. I turned to [the Danish journalist] and I was like: ‘Fuck! That was good, wasn’t it? Let’s do it again!’ We drove around the back of town again and we came through the same street! [Laughs]

It’s kind of nice to come back 20 years later. I got out of the minibus in Prizren and I was like: ‘What??’ If I think now of all the wars I’ve covered, it’s not very often that you get to see this.

This was a pretty miserable place. People were terrified. What they had gone through: the Serbs, NATO, the whole thing…. Prizren was flat and desperate. Seeing it again, I see an incredibly positive change. Showing the film means so much to me, it’s like a full circle. This place is where it all kicked off for me really, and now I’m back.

What motivated you to continue working in photography after Kosovo, and working in conflict zones specifically?

As a soldier I had always looked at war from a military perspective: the weaponry, the tactics, our opposition. When I was in the army, it was the Cold War. I didn’t get to fight because I was in Germany, but we were the frontline against Russia, and it was quite tense. No one really ever knew what was gonna happen, or if it was gonna happen. So that was my preconception of war because that’s what I had been trained to do. I had a military perspective.

But when I was in Kosovo I saw the real results of war. The people who always get the shit end of the stick in every conflict aren’t covered. The people with no voice are the women, the kids. They get moved about, they get locked away, they starve, they have to bring up families.

Most bombs dropped and most of the bullets fired are not precision guided, they are not really targeted — most weapons aren’t smart. Those weapons land somewhere, and the place where you really see the end result of it, of the shit that is thrown about in war, is being with the women and kids. That’s what I saw for the first time in Kosovo, and that was my guiding light for the next 20 years.

That was my connection with Marie [Colvin]. With this film we never set up to condemn or justify any of the reasons for why the war was there. Forget the reasons, these are the results.

Everyone thinks that war journalists are just war junkies, and I hate that. I hate this thing that ‘it’s all adrenaline.’ If I want adrenaline I’ll jump off a bridge with a bit of elastic tape on me.

It’s not that we were war junkies, but if we want to cover war from that angle, then you have to go through some extreme circumstances to get to that point, because those women and children are never in a good spot, in a nice, safe place. They are always at the shit end of the stick and that’s what, from seeing Kosovo up until when I walked into Syria, that’s what I wanted to cover. The reality for the majority of the people is hell.

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Journalists working in the most recent wars, from Iraq to Syria, have pointed out that war used to be more symmetric: The enemy was clear, you know who is fighting with whom, and there was a relative respect towards foreign journalists. We could see that in the Kosovo war for example, or the other wars in Yugoslavia. Now this has completely changed, and perhaps the best example of these asymmetric wars is the Syrian conflict…

That’s quite right. We’re targeted now. Even in the Balkan wars, you could cross over with a bottle of Scotch and 200 Marlboro, slip them to a Serb general and go and talk to the Serbs. That was possible then, because although it wasn’t a clear cut war there was still quite clearly defined sides. So you could talk to the UÇK and if you needed to talk to the Serbs, then you could do it. When we were in Syria, the concept of going and getting the other side… it was just not happening. It would be a suicide mission.

This kind of crept in, and I think there are numerous reasons for this. When I used to take a picture 20 years ago it would be a week before it would go anywhere. I could take a picture today, and it could be on the front page in an hour. When people started to realize that journalists can actually affect the outcome of situations and that it is so instant — all of a sudden you stopped being what was considered an observer.

We can manipulate the outcome, not the physical outcome on the ground, but the perspective from the world can be manipulated. If there’s a massacre, and I take a picture of it, I can have that out in an hour.

We do it because we think we can make a difference. When we were in Syria, Marie and me thought that if we show the world, we could make a difference. You’re not doing it for fun. The reason you’re there is to show the people what’s happening. I always said that we go in, we come out, we have the story, we have the pictures, and we offer it to the world for consumption.

The reason you do that is because you hope the reaction will be horror, appall, because we’re no longer in the dark, we now have knowledge. Now, the frustration is: ‘Yeah, well, this is what’s happening down here. We hope you have enough integrity to believe us. Now that you have this information and you can tell the world to act.’

I think that in Syria they realized this very early on. When Marie and me got there, our names were on a list, with our photographs. We have the documents that show it. ‘Kill them’ — that was the order issued by the Central Emergency Cell handled by Bashar al-Assad. They had the order: ‘If you find them, kill them.’ So we had a death sentence on our head from the moment we left Beirut airport. That is something that is relatively new.

We rattled their cage. We had the cheek to broadcast live, in the middle of their killing fields. They were slaughtering people and we were there live, and that’s how it’s changed. Now it’s like: ‘Kill them. We don’t need this shit getting out — take them out.’

This gets to another level of complication when it’s not just the government after you but multiple sides. In Syria, groups like ISIS and others have been targeting foreign journalists very clearly…

To the government we’re a threat, because we are getting information they don’t want out. On the other hand, in the next village you’ve got ISIS, and to them we’re a commodity, we may as well be driving around with ‘ATM’ written on our forehead. You catch a foreign journalist and you get paid three million for each of them.

Then you get the fundamentalists who want nothing more than to cut your fucking head off because that’s their modus operandi. That’s how they work, through terror. My mates, like Jim Foley, were executed. It’s terror, it’s a tactic they use.

So you’ve got the government trying to kill you because they don’t want the story out, you’ve got these guys who capture you because you’re worth a fortune, and you’ve got others who want to cut your head off because they fundamentally wanna cause as much terror and horror as possible.

In the midst of this you’re sitting there going: ‘Who do we know? Who do we trust, and how are we gonna move?’ It makes the basic job of telling stories incredibly fucking insane.

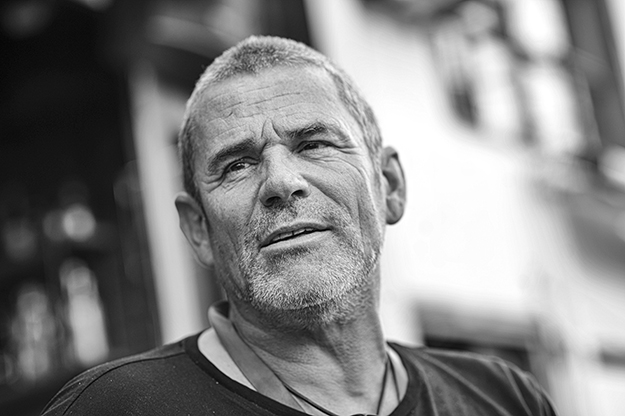

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

In “Under the Wire” we see a Conroy and a Colvin who are tirelessly committed to telling the story of the victims. But how does this environment affect getting to the side of the perpetrators, to understand it? Colvin had access to people like that, like Gaddafi, for example, but in the Syrian war, how does this environment influence the story?

We’re aware that we can become compromised because we’re so close to [our contacts] there. You’re relying on these people to get you transport, for your movement, for you staying alive, for your food. You’re so dependent because it’s the only way.

And we have to push it even further, to get to [the story]. You trust them but you know you’ve gotta ask for more. You’ve gotta get closer and closer and closer. You’ve gotta get them to dig up the fucking bodies.

Everyone is so savvy now, there is a danger you’re being used. That makes it incredibly difficult. You’ve got your reputation to think of. You have to think: ‘I’m gonna hold myself up to scrutiny on this.’

Marie was killed because we were trying to get too close to what’s happening. But you can’t. You simply can’t. As much as we’d love to. I can’t walk through and cross that frontline ‘cause sometimes there isn’t even a frontline to cross. If there was a frontline, chances are that I’d try to cross it.

It’s a society that is broken apart. These were people who were killing their fucking neighbors. There’s no frontline to cross, we’d been on it. But there becomes a point where it reaches an end: We’ve seen the body. That made it incredibly hard because the level of verification you have to go through is extreme.

In this environment, what are the ethical discussions with your colleagues when you are on the ground? What are you most concerned about, and what is the rule that you won’t break, if there is one?

With the people, there is one thing that they’ve got left and it is the same in every war I’ve covered. There is one thing they have left by the time they’ve been degraded, and when people have been killed, and slaughtered and moved, starved, and raped. There is one thing they’ve got left and that is the vague hope that somehow everything wasn’t in vain: that somehow you got that story.

When everything you have is gone, people knowing is vastly important. It becomes more important than you’ll ever imagine — the fact that there is somebody there, that they think cares enough to be there. The Syrians told them we were the enemies, the West, and that the Russians were their allies. But all of a sudden there is a couple of Westerners there who are in a pretty extreme situation, and they wanna know their story.

I don’t think we were ever refused through people’s grief and horror. I don’t think anybody has said: ‘I don’t want to go any further with this process of telling.’ When everybody has lost something they can’t sit around with each other going: ‘Ahmed is dead, Bashir is dead,’ because they all know. They’ve all lost someone.

Then all of a sudden someone comes and says: ‘Tell us what happened.’ That is a big thing for them to be able to do. We want people to tell their story, but to do that we need to tell them that this is gonna be uncomfortable: ‘Can you take us to the graves? Can you describe in detail…’

But I’ve never had anybody go ‘you’ve gone too far.’ Never. That’s why I think truth and reconciliation works, because you get people to say what happened, to actually tell their stories.

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

I was wondering whether this is something that you feel close to your heart because you also lost a very unique partner in Marie Colvin. Does this process of telling your story through the book and the film help you in that way?

It saved me. Marie wasn’t just a work colleague. If you do this job, I could be a stranger, and then we go through a firefight, and be under attack, and very quickly that stranger you met four hours ago, you go through something [together]. Friendships on the fire become strong very quickly. Marie and me did this for a long time. My reason for being was what we did. And all of a sudden she was gone.

I was the same, I woke up and I’d been in London 12 hours, and had this massive operation, 14 hours long. Half an hour after I woke up I said: ‘Open the doors, let the press in.’ I did like eight hours of interviews — every channel in the fucking world was there, and I sat there for eight hours. I was gonna tell the story.

I never really thought about it in the same sense, but I was doing what other people do. Someone cared, people were asking, and I was gonna tell people about it. I’ve never really compared it but yeah, it was the same.

I wanna tell everyone what happened. When I was injured and [Marie] died, I became not an observer any more, all of a sudden I was in it. I was in the same position as every one of them that was injured. There was no special treatment. I was as fucked as the others.

On the way in to Homs it took us three days to get into there, and I remember taking a photograph of this guy laying in bed, and his leg was really badly injured and I snapped him and thought: ‘Fuck, he is gonna go out the same way that I just came in, and he is not gonna make it. He’s fucked!’ Two weeks later, when I was on the way out, they threw me in this room, and I was in same the bed as the guy who I had photographed with the leg wound. I was laying there with a big hole in my leg and I know the way out from there. Now I’m fucked!

That’s when I realised that you’re not just a photographer doing your job anymore. Marie died with the people she was reporting on, so she became part of [them]. I realised that I was too, and it was a flip point. It was very cathartic being able to tell the story. Not by chance or by choice, but by circumstance, we did become part of what we were doing.

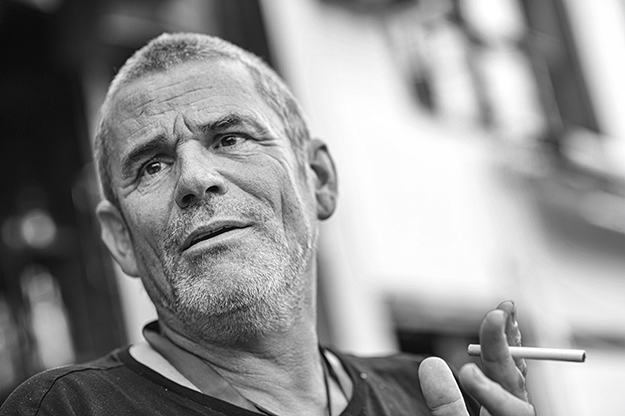

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

In terms of photography, we’ve become very used to seeing the same images sometimes, the same style and aesthetics. There is a certain definition of what the aesthetics of war look like, even when the wars are taking place in different countries and cultures. How do you approach this fact, especially with people becoming used to these images, and the impact that the images can have?

It’s actually really fucking hard shooting war. Forget all the dangerous shit and all of that — the actual art of photography is really fucking hard. I’ve been in the most ferocious firefights, and I’ve been shooting away — the back of my head knows bollocks, it’s all going off. Now if I were shooting video it would be fucking great because it’s: ‘Wizz! Bang! Boom!’ You’ve got a load of guys crouching behind the car shooting — but when you shoot, all of a sudden they all look like catalogue models.

You get about three seconds, if anything, where you’re driving along and all of a sudden the shit hits the fan. The time you’ve gotta be pressing the fucking button is when the guys in the truck realise that they are under attack and they all dive out the truck. If you don’t get it then, by the time they land, they’ve all got their their head down.

This is the thing that sickens me so much professionally about photography. It took me quite some time to get really good, to not put my head down at that point when the attack happens, when all the soldiers, and the rebels, and anyone with half a brain, gets their head down. Because if I don’t get the movements, the dynamics and the expressions of that, I’m just gonna have a picture of people with their head down. It’s kind of a different aspect of it, cause that’s the actual conflict. That’s the picture that will get on the front page, the guy throwing the grenade, or whatever.

You’ve got 3 seconds. You go against your instinct, put your head up, frame, fucking do whatever you gotta do. Not only that, you’ve gotta be aware of your paper. You’ve still gotta tell that whole story, and you’ve gotta make an editorial judgment at that very moment.

It’s about composition, about content, the technical aspect of doing the photograph — and that’s kind of one side of it. Hopefully, you’re not just gonna get one shot but you’ve gotta sell the story to your editors on one shot.

The other side is the style. Do we get too used to seeing the bullet holes through the window? The only judgment for me is: If I can look at the image, and I’ve got the major component of the story in that shot, and it’s almost self-explanatory. If it’s not mainly self-explanatory, I don’t use it.

I’ve got a week to get it because we’re a Sunday paper, so I’m not very stylistic. I work on the basis that if Marie gets her words, and I get my picture — I know that the end result is bigger than the sum of the two parts. The only thing that guides me is whether I have really done enough to capture that story in pictures. I’m aware that there is a danger of people getting too used to a style, but it’s not something that you can do when you’re in the field. Your only guideline is to tell the story to the ultimate best.

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Journalists often have a “natural” competition in getting a story out. In war zones, perhaps because journalists are working in harsh environments, you’d expect them to really help each other… But how is it on the ground among peers?

You saw a perfect example in the film. [In “Under the Wire”, the night before Colvin and Conroy planned to exit Homs, three foreign journalists arrive to the media center where they are based, ending their exclusivity as the only Western journalists in the siege.] Marie tells me, ‘Paul, you still wanna go now that your [friends] are here?’ (Laughs). [Our editors] were trying to get us out, and then these friends show up and she goes, ‘still wanna go now that the Euro trash are here?’

That was real. But we were a Sunday paper, and we’d file on Friday, or Saturday the very latest. One time when a friend got shot in the head doing Gaddafi’s palace, a guy from Reuters came to us and was like: ‘What the fuck are you doing getting shot in the head on a Monday when you’re a Sunday paper?’ Monday is our day off and it’s a Monday and we’re working.

We used to have to guard our stories. We never had a day off. We’d file and then we’d start again. So say we get something on a Sunday, we had to guard it all week from everyone. Even our translators and fixers were forbidden to talk, because they just gossip: ‘Oh, we’ve been doing the mass graves, what have you been doing?’ And me and Marie would go: ‘What the fuck have you been doing? You don’t talk to them!’

Sometimes we’d finish a story on Thursday night, wake up, check The Times, and it was like ‘Fuckers! They’ve got it – it’s Friday!’ [Laughs]. It was terrifying the longer the week went on, because if someone gets it now, we’re fucked. Sometimes we’d have to find a plan B. If there’s ever a bar, then everyone in the bar is asking: ‘What have you been doing today?’ and you’d be like: ‘Oh, nothing, nothing happened in Iraq today.’ [Laughs]

While you were taking questions from the audience here at DokuFest, one question kept coming up about the impact of the images you take in this era of Facebook. We keep hearing the stories, we see the images; of the Mediterranean sea becoming Europe’s biggest cemetery, of Aylan Kurdi washing up on the shore… We see them, we get outraged, but their impact is temporary. You wanna tell the story because it matters and needs to be told and if journalists start thinking that it doesn’t make any difference anymore, it would probably get worse. How do you reflect on this reality, seeing photos like these that we simply get used to — the impact of the work of journalists that continue to risk their lives… How do you reflect on all this?

I was in Paris when the photograph of Aylan Kurdi came out. I was called by a radio station in England asking me: ‘Paul, explain to us: I’m sure you have a thousand images of dead kids on your hard drive’ — which I do — ‘what is it about this one image? Because that image has really captured the world’s imagination.’

It’s almost like a serendipitous thing. Of course, I can pull out something that’s similar but something comes along now and again that will capture a moment, as that image did.

It’s part of why you’re there doing it. Do you feel you made a difference? And if you didn’t, why do you go back the next time and do it again? I can’t imagine not doing it. The night before Marie died we were sitting there, the buildings were falling down around us, and she said: ‘If you weren’t being paid, would you still be here?’ And it was like: of course I would, you silly woman! I didn’t even have to ask her, and that gets to the bottom of it. It’s not a job, it’s a vocation. You’re driven to do it.

So, the amount of times you’ve walked away from something going: ‘Did that make any measurable difference?’ I don’t know, but would the world be a better place without it? I bet you for sure it wouldn’t. That’s enough for me.

Very often it’s not a measurable difference at the end of it, but should people stop doing it? Absolutely not. I would rather see too much of it than find out that there’s been a hidden war that’s been going on for five years that we don’t know about, because no one could be bothered to go and do it. I prefer a world where people are still driven to go and do it, and maybe do it for ten or twenty years. Did it make a difference? I don’t know but it’s worth a try. And I’d rather live in that world than in a world where people just don’t bother.K

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. The interview was conducted in English.

Feature image: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.