Polip’s spread beyond Prishtina makes 2020 edition truly borderless

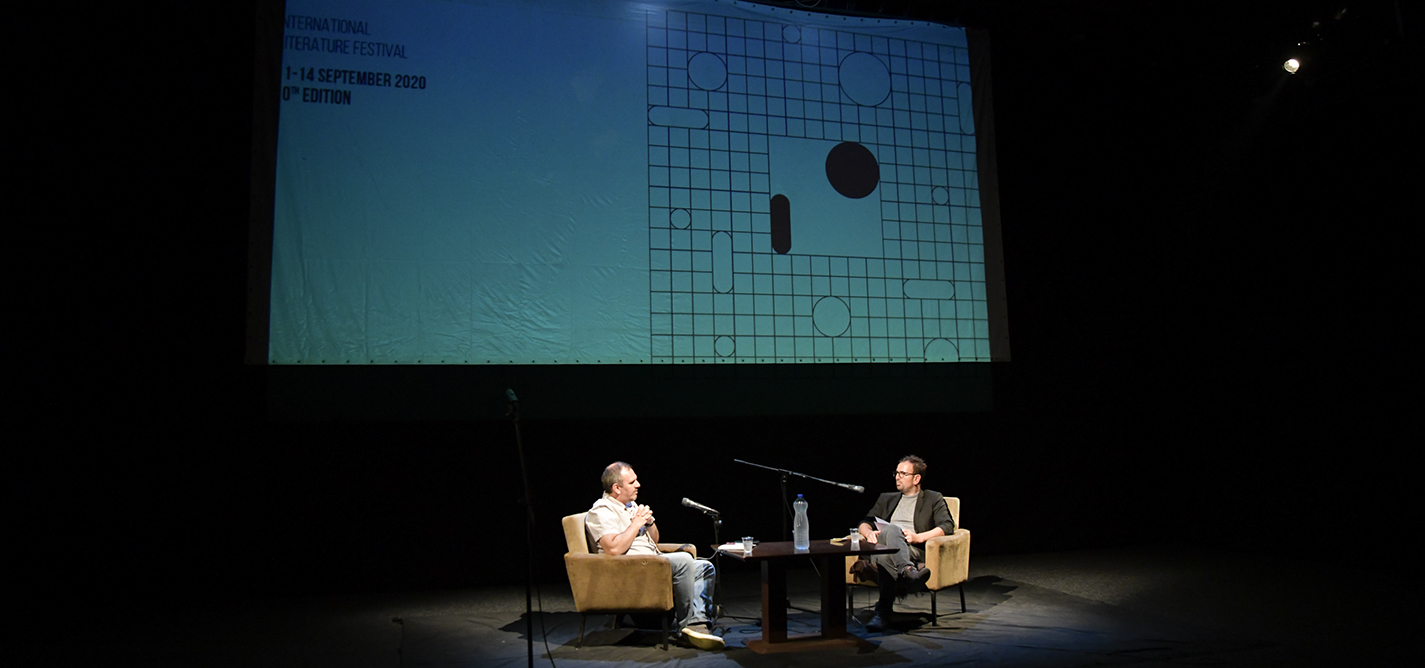

Literature festival explores change through new means of expression.

Could a festival built upon the idea of connection have the same kind of impact with its participants distanced from one another?

The potential for change has been embedded in the festival from the beginning.

Turkish poet Naduran Duman spoke with the sea at her back.

Natasha Tripney

Natasha Tripney is a writer and theater critic based in London. She is international editor at The Stage and co-founder of Exeunt, a digital theater review. She is a contributor to the Guardian, the Independent and Tortoise and has a particular interest in theater and performance of the Western Balkans.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.