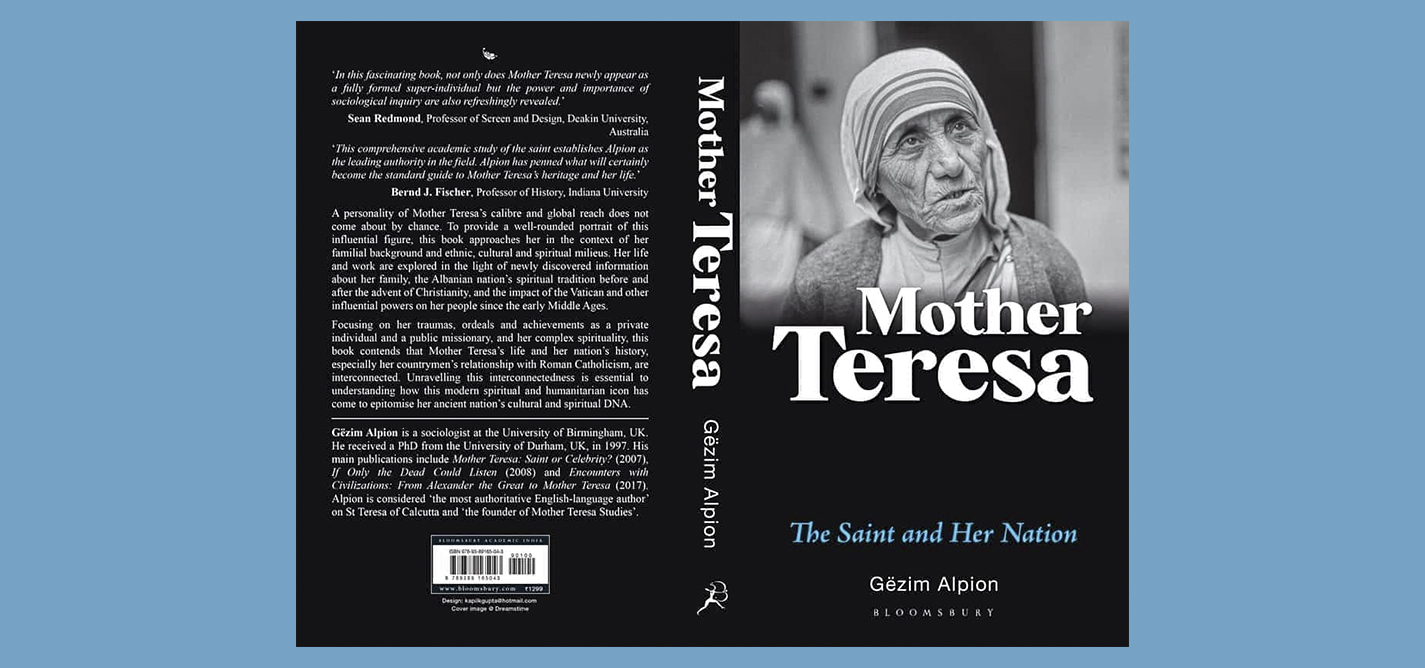

Reviewing ‘Mother Teresa: The Saint and Her Nation’

A look at Gëzim Alpion’s latest work on the world’s most famous Albanian.

Alpion argues that Mother Teresa’s life and her nation’s history are interconnected.

For Albanians, national identity is a notion that includes and transcends their pre- and postmonotheistic existence.

One of the most fascinating topics that Alpion has probed in his research on Mother Teresa is the darkness of soul.

Ridvan Peshkopia

Ridvan Peshkopia is a lecturer at the University for Business and Technology, Kosovo. He received his PhD in Political Science from the University of Kentucky and spent a year as a postdoctoral fellow with the George Washington University. His research areas cover mathematical and statistical modelling for political science, political behavior, political theory, migration studies, peace studies and film studies. He shares his life between Gjakova and Tirana.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.