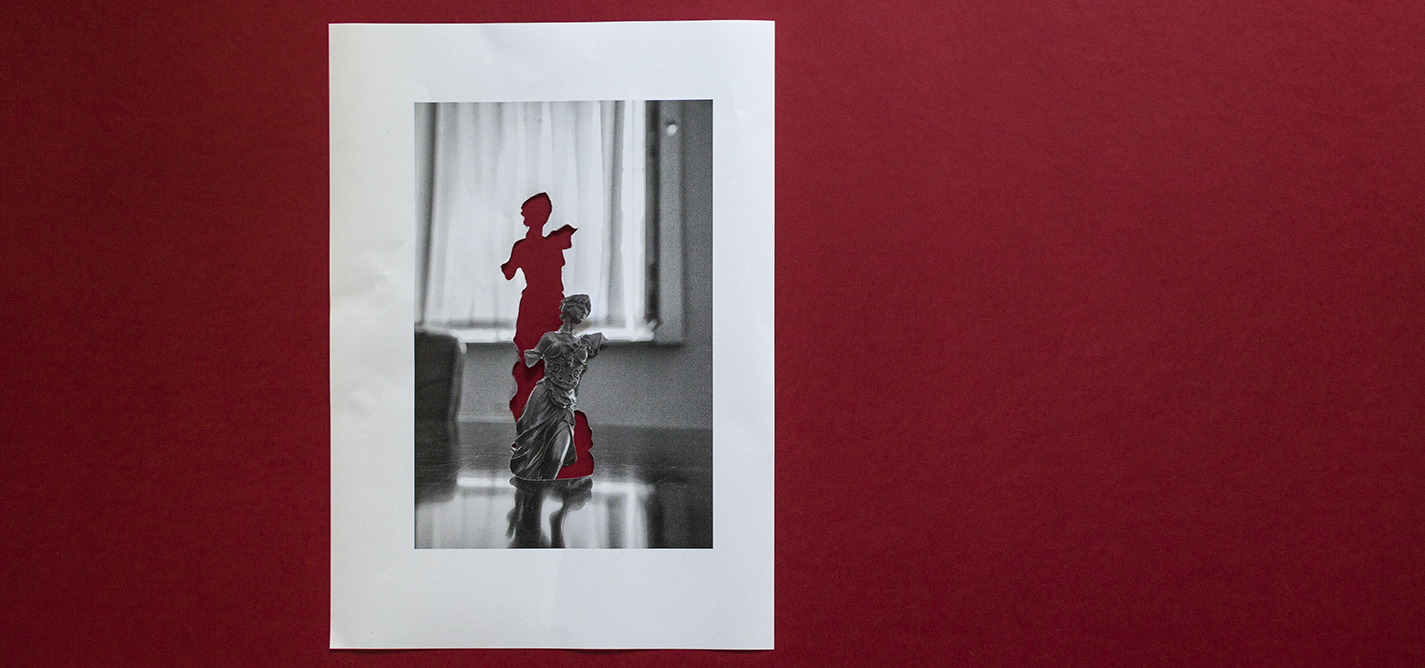

The past must be confronted, continuously

K2.0’s latest monograph dives into the past, for the present and future.

Fundamentally, and at its core, transitional justice is about whether the lives of citizens have become any better.

While the region needs to move forward, it cannot be at the expense of forgetting or not addressing what has gone before.

Besa Luci

Besa Luci is K2.0’s editor-in-chief and co-founder. Besa has a master’s degree in journalism/magazine writing from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism in Columbia, U.S..

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.