Yesterday marked the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin wall. Citizens of the German capital released thousands of balloons into the air last night as a symbolic celebration of the freedom that came with taking down the concrete bricks of that dividing wall. To commemorate this monumental day in history, we have released a story from Kosovo 2.0’s Migration issue about the physical barriers humans create between each other. To read more stories from the magazine, get your copy here!

In 1948, my maternal grandmother, who lived in Shkodra, Albania, married my grandfather in Tivari, Montenegro (then part of Yugoslavia). Two weeks later, relations between Albania and Yugoslavia deteriorated and their borders closed so tight that no human soul was able to cross to the other side. It was 50 years before she saw her family again.

There is a well-known legend in Shkodra about how the town’s castle was built, and it involves the struggles of three brothers who were working on erecting its walls. Every morning, they would find the work of their previous day undone, and they would stare at the rubble of bricks wondering what could have happened during the night. Finally, they sought a wise man’s advice and were told that in order for the walls to stand, a sacrifice had to be made. It had to be one of their wives — but which one? They decided that it would be whichever one happened to bring them lunch the following day. Understandably, the oldest brother couldn’t resist and out of love he disclosed the plan to his wife. The second brother did the same. So the task of bringing lunch fell to Rozafa, the wife of the youngest brother. Despite the fact that she had just given birth to her infant son, she accepted to be sacrificed — to be walled-in — under one condition. She asks for her right eye to be left exposed so she could watch her infant son grow, her right breast so she could feed him, her right arm so she could hold him, and her right foot so she could rock his cradle.

Justifications for why we might go to such lengths to separate ourselves from others range from protection against barbarians or invading armies to motivations as nebulous as ideology. Both Shkodra and Tivari are cities that grew under the protective shades of fortresses — the castles of ancient Scutari and Antibari. When my grandmother got married in 1948, the walls of these fortresses were no longer under siege, the Illyrians were long gone, the Romans long collapsed, the Byzantines long fallen, the Venetians long forgotten and the Ottomans long Balkanized. At the moment when the bricks and mortar of walls were not able to keep people apart, a new and improved type of barrier came to existence — an invisible one fueled by political dogma.

At that time, both Albania and Yugoslavia were involved in a communist love triangle with the Soviet Union. Through their political flirtations, they tried to prove themselves worthy of this new lover. It was such a passionate affair that it nearly resulted in a marriage between the two. Of course, when the third comes to tango, things become a bit more complicated, passionate and wild. People start losing their heads. Blood runs high. And then, all of a sudden, and because they bitterly disagreed as to who was a truer communist and who was more in love with their Soviet suitor, their relationship came to an abrupt end, resulting in the closing of the borders.

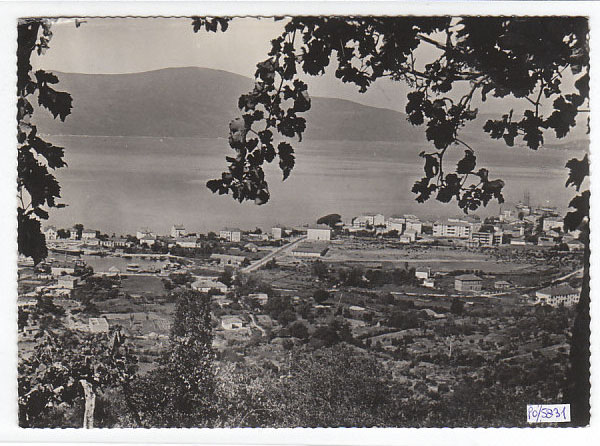

I remember sitting with my Grandmother in her garden in Tivari, under the cooling shade, smelling oranges and pomegranates in bloom, as she would longingly tell stories of her brothers and sisters whom she did not see for decades. I remember that my gaze would start panning from her face to beyond the garden treeline, toward the dark-green olive groves in the distance and up to the gray stone walls of Tivari’s Old Town, which would slowly morph into the dark blue of Mount Rumia, standing there as if guarding the town’s back.

Before the border closed, my grandmother’s brother used to come visit her often. Back then, it was a two-hour bike ride through some moderately mountainous terrain. After the border was closed, all her family was able to do was send letters. She kept them in a special box. I knew better than to even approach that mysterious box, no matter how much I longed to explore the arcane-looking stamps, or the white envelopes with red and blue edges, or the papers that looked half burned from age and time, or the blue ink that had begun to fade and blur (making the writing barely legible), or the yellowed photographs of people I never saw but who were supposed to be my mother’s uncles and aunts. There was too much sadness in that box, so much that it created this invisible barrier preventing me from coming near it. A wall of tears? A fence of loneliness? A barrier of longing and nostalgia? Whatever it was, it was impenetrable even to the powers of my mischievous nature.

Centuries later, Rozafa’s ghost had returned to haunt us all. She was reincarnated in the longing tears of my grandmother and in the pain of her homesick heart. Someone had to be sacrificed to keep the ideological fortresses erect. Her melancholy was the wall in which she was buried alive. The only things left exposed were her trembling right hand (to hold the letters), her right eye (to drip tears and blur the blue handwriting), and her chest (to keep the envelopes close to her heart as her foot would shake while she got lost in her thoughts).

A City of Walls

From the border between Albania and Kosovo — the very same one that was impenetrable for 50 years — one can drive north to Prizren in 15 minutes. After passing through shades cast by the rows of tall trees on both sides of the road, the old fortress comes to view. From the top of the hill, the Kalaja overlooks the entire city. Its walls, those walls that prevented so many enemies from gaining access to the secrets and bounty it once held, are now disintegrating from the constant stress, war and, finally, neglect that were sustained through three-and-a-half millennia. As its bricks crumble, it silently contemplates the legacy of its existence. Observing the city’s chaotic architecture, it perceives many smaller and less permanent walls forming fractal patterns in its shadow and it suddenly becomes aware, as they spread down hill like the tentacles of some giant stone nightmare, that it still continues to influence the architecture below.

Prizren is a city of walls. To prove this, I don’t have to go further than my family’s home there, whose tall walls separate our “territory” from that of our neighbors. As the walls of a castle are only as effective as its gates, we made sure that ours was a gray one made out of thick metal that I assume would be impervious to battering ram attacks. On top of the gate stands a grand sign advertising the name of my father’s urology practice (which in case of a siege would prove extremely beneficial in slowing down the first wave of infantry). The logo to the left of the “UROPRIZ” inscription is more like a crest denoting that this stronghold belongs to the House of Kidney and Bladder of the Bytyçi clan.

For a communal society that cherishes making contact with people, it is astonishing how much energy is spent on activities that do the very opposite. Before our family would visit neighbors or friends for tea or coffee, we would always have to wait for our mother in front of those very gates as she would obsessively make sure that they were properly locked. Her light cotton dress would feel as heavy as armor while she bustled from room to room, locking doors like a general before the siege. Descending the stairs, the floral scent of her perfume would diffuse throughout the house in much the way that motivation, courage and fear spread through infantry ranks when they are faced with news of the enemy’s approach. She would turn the keys and with every click, the fabric of reality would blur, morphing her makeup of red lips and dark eyeliner and blushed cheeks into a kind of war paint. Being five minutes late was nothing compared to the benefits of ensuring the fortress would be impenetrable for as long as it took to conduct our visit as guests.

But who were the enemies, exactly? Thieves? Unlikely. To the right of our home-fortress lived my uncle — my father’s brother. His three sons changed professions more often than I swapped loyalties to my favorite cartoons, but eventually found their true callings as car mechanics. If the House of Oil and Grease of the Bytyçi clan were to have its own crest, it would be difficult to choose between the one with three cars and the one involving a hammer, a wrench and a screwdriver (each standing for my cousins’ personalities). To the left, the high wall separated us from yet another set of three Bytyçi brothers — this time with no blood relation, only a coincidentally similar surname. Since they were all engineers, we may refer to them as the House of Gears and Steam.

My mother’s instincts were probably fueled by the idea that someone might break in and steal all that medical equipment my parents had worked so hard to assemble over the years. In this way, just after the Kosovo war (when social order had fallen into that state of functional anarchy so common in recently post-conflict places) and acting as governor of the Uropriz fortress, she decided the time had come to upgrade the security. And just like Romans did by adding a new layer of fresh stones, or as the Byzantines did by making their towers higher, or as perhaps the Ottomans did by installing those state-of-the-art cannons, so she decided to raise the height of the walls around the garden by about half a meter, and to install metal bars on every window of our home. My sister’s complaints that she felt like she was living in a prison were dismissed as childish concerns.

But if the upgraded walls did anything to slow down possible thieves, they were never successful in preventing the Mushmulla tree in our garden from spreading its branches beyond the Uropriz fortress and into our neighbor’s “territory.” (I would get jealous that our ripe medlar fruits could be easily picked and eaten right from the garden of the House of Gears and Steam.)

Just like no wall, no matter how high, could contain the Mushmulla tree in my garden from sprawling its branches, and just like the branches of family trees from both sides of the border were eventually re-intertwined, the structures of Prizren’s Kalaja, whose purpose was to separate people, are now the most romantic spot in town; this is where lovers open the gates of their hearts to let each other inside the walls of their lives.

One would think that we have evolved considerably since the time of our violent ancestors, but the reality is that we are all still the same old homo sapiens, hard-wired to thrive in our small groups, fostering cohesion by hating outsiders and preventing them from gaining access to the things we hold most precious by building high walls.

Perhaps Rozafa’s misfortune is somehow ingrained in our very DNA, meaning that it can be transmitted through and over the generations. That might explain my grandmother’s melancholy fate, as well as my mother’s obsession with high walls and locking doors. That means that I, too, have some of Rozafa’s blood running through my veins. I could be one of her (great-grand)sons, whom she still observes with her one eye peering through the wall.

A Dog’s Life

Maybe I too carry Rozafa’s curse, an old malediction scattered like stardust through space and time, as I now split my existence in between two continents and feel that I might not quite belong to either. I exist in between the confinement of Kosovo’s borders and the vastness of the United States. I can barely travel anywhere with my Kosovar passport (to four countries, in fact), yet I continue to delude myself that the opposite is the case by living in the most open place in the world (until my visa expires, that is).

As a person who hates paperwork, I have an aversion for the visa application process. I find it to be as mentally torturous as being water-boarded with electric wires attached to my you-know-what with a pile of vaguely canine pedigree documents in my hand.

For it is truly a dog’s life, this existence spent leashed to the doghouse of the nearest embassy. A western reader might miss the cultural context in which I use the word “dog,” perhaps filling his or her mind with frolicsome puppies — but I am not thinking of these sorts of dogs. I am thinking of the dogs of the Kosovo street, the stray wolf-dogs who roam the alleys like vagabonds wielding knives. I am thinking of the sort of dogs who are starving and who could attack at any minute, who in their hunger could bite you and from their foamy mouths transfer whatever virus turns you into one of them, a zombie were-dog. Their pelts are drenched in rain and mud as they scavenge dumpsters for a bone still bearing the smell of blood, eyes glowing and lips curled. They spot you in the alley, and they silently agree with the whole pack to savagely attack you. That kind of dog must surely be leashed for safety.

Back in Tivari, my maternal uncle had a tiny mutt we called Robbie who was always leashed to his doghouse. I cannot say with complete certainty whether my uncle found him in the street as a puppy, or if he offered to adopt him from someone after being hypnotized by his beige-blonde pelt. Once fully grown, Robbie was barely bigger than when he was a puppy, but he was fierce and full of the sort of stupid that got him into barking matches with dogs five times his size. One time, he managed to break free of his leash. We couldn’t catch him for three days, and we were able to subdue him only after he had spent all of his energy running like crazy in weird circles around the house, those celebratory arcs of his freedom.

Sometimes I feel like Robbie, leading a dog’s life, dreaming a dog’s dreams and seeing dog visions. I am in an infinite field. I start stretching my legs and slowly pick up my pace until I am running. I almost can’t believe how good the green grass feels, I can’t believe how pleasantly the fresh air stings inside my nostrils, I just love the… kkkhhhkhkhkh. Oh God! Damnit! My throat, I can’t breathe! My neck, it’s all bruised. I shouldn’t have run so fast with this collar on.

Sometimes I wonder if, high up from the walls of Shkodra’s castle, Rozafa’s right eye still observes how her great-grandsons are growing up. I wonder if her ghost sees me for what I have become: a dog, fenced in (just like she was walled in) by an invisible barrier. I have spent my life shaking in fear like an abandoned mutt in the rain while holding my passport at embassies and border crossings. I would rather be a stray street dog, infested with fleas, than to have this scar on my neck from the collar of bureaucracy.

The Land of Quantum Freedom/Entanglement

You would think that once I saw the endless cornfields of Iowa, I would feel liberated, and might even start running uncontrollably like my Robbie when he broke away from his leash. Truth be told, the vastness of those fields proved to be a type of a barrier itself. In a place as spread out as the American Midwest, I couldn’t go anywhere without a car. On the other hand, once I got a car, or borrowed one from a friend, I could choose any place between the Atlantic and the Pacific.

American vastness exists in a quantum state of being — it both prohibits and enables freedom of movement. It is the geographic equivalent of Rozafa, whose existence was split between the two sides of the wall. Neither dead nor truly alive, suspended in space and time, she’s the mythological equivalent of Schrӧdinger’s feline experiment.

With my discovery of that vast expanse so ripe for my exploration, the concept of borders that I had previously known started to blur to the point of nonexistence. All I had to do was look at the gardens. In Prizren, my garden was surrounded by tall, fortress-like walls that explicitly denoted the borders between neighbors. I was astonished to find out that in the Midwest, people’s lawns would morph into each other and the only way of figuring out whose territory I was stepping on was by noting subtle changes in the color and length of the grass. This was also when the boundaries of my mind begun to blur, and walls begun to crumble and fall.

Thus I embarked on my first road trip and crossed half of the United States, from the Midwest to California and back. In subsequent years, I would repeat this on many occasions, completing like a puzzle the map of the states. I drove through the red sands of Arizona; tried to find the edge of the horizon through Midwestern cornfields; saw how my face and body were transformed at The Bean sculpture in Chicago; got stuck in Los Angeles traffic; witnessed the blue twilight close to Salt Lake City; was convinced that everything is really bigger in Texas; sipped merlot in the Napa Valley; ate corn chowder in Boston (and compared it to the one I had in San Francisco); swam in freezing January water in Miami; visited the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland; was disappointed by the quality of the beaches in Daytona; witnessed Fourth of July fireworks in Washington, D.C.; forgot that I once visited a NASCAR racetrack and tried to remember if it was during the trip to Texas or Florida; went to Walmart in Missouri; bought a cowboy hat somewhere near Austin (or was it Houston?); ate half a bag of Florida oranges bought at some highway rest stop…

In the course of these roamings, I eventually found myself in Times Square, hypnotized by the bright and colorful screens and loud lights. Engulfed by the crowd, I felt as if the walls of my fortress had fallen and the enemy soldiers had overrun the gates. I felt simultaneously overwhelmed by the awareness of my insignificance in the grand scheme of things and full of purpose and meaning, as one does when they feel that they could achieve anything.

Even after living in New York City for so many years now, I still feel that simultaneous duality of loneliness and community. It might seem paradoxical to feel solitude in a place so crowded, but just like the walls of Shkodra’s castle needed Rozafa, Manhattan requires a sacrifice of its own, and makes you put up walls and barriers to separate yourself from all the other people. This is probably the only way to remain sane here.

Life in a big city exists in a seemingly impossible state of quantum entanglement, like a particle occupying two spaces at once. Just like Rozafa’s existence was split between the two sides of the wall, so is the existence of city dwellers like myself who must constantly fluctuate between the quest for fellowship and the struggle to maintain autonomy.

Maybe Shkodra and Tivari and Prizren and New York City are not so different after all. They all have their own versions of fortresses. And we are all still the same old homo sapiens, hard-wired for erecting walls, fences and borders. We just got better and more sophisticated at building invisible ones. We all have a little bit of Rozafa’s blood flowing through our veins. Her legend is inscribed in our DNA. Encoded in those genes, we find loneliness when we are among the crowds, and seek community when we are alone.