Like many other parents, Danijela L. from Zagreb has spent the year juggling between her job and the children’s needs. Her two girls — one attends kindergarten, and the second one is in primary school — were often “taking shifts” between self-isolation and being in school. Danijela’s days were reduced to cooking, food shopping, cleaning, helping out with the older child’s homework, and entertaining the younger one.

“I’m not unhappy. I’m just locked up in these four walls and more pessimistic than I used to be,” Danijela told K2.0, adding how her concentration has been totally wrecked because she is doing multiple things simultaneously, and then stops everything to do something else.

Even though she admits to having a tough time, Danijela says that she still hasn’t asked for psychological support, not for herself or her children.

“Despite it all, I’m still handling everything properly,” she says.

Many would say that Danijela did well in the pandemic: She is healthy, has a roof over her head, lost no one close to her and has a job. As of this writing, the pandemic has taken 7,623 lives in Croatia, 8,871 in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 6,623 in Serbia, and 2,222 in Kosovo.

In a context where everyone is losing their loved ones, health, jobs — while still struggling to survive — speaking about mental health may sound like a luxury. However, that is definitely not the case.

(In)visible pandemic-induced consequences

Results from a study conducted by the University of Manchester, UK, show that, in December of last year, more than 42 percent of respondents in the U.S. reported symptoms of anxiety and depression, an 11 percent spike in comparison to the previous year. The research data suggests that the same situation is present elsewhere in the world.

These results are related to the pandemic itself but also to the economic consequences that drastic lockdown measures inflicted on society. Thus, according to the data from a World Bank study, titled “Economic and Social Influence of Covid-19,” from spring 2020, the entire Balkan region reported a record high employment rate and all-time low unemployment rate at the end of 2019.

By April 2020 as much as 40 percent of the 2019 increase in employment was lost. Besides this, over the last year, the GDP has decreased by 9.6% in Croatia and 6.5% in Serbia, which is the largest drop in production since 1999.

According to an October 2020 study conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 130 countries, the coronavirus pandemic has completely disrupted or hindered the work of mental health services.

Simultaneously, according to an October 2020 study conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 130 countries, the coronavirus pandemic has completely disrupted or hindered the work of mental health services, although this assistance is increasingly sought after. Eighty-nine percent of the countries participating in the study confirmed that mental health and psychosocial support are part of their national preparedness plans, it has turned out that a mere 17 percent have the adequate resources to finance such services.

The Balkan region’s nations are no exception.

“At the practical level, sufficient support services aren’t available,” Marina Milković says. She is a psychologist at the Zagreb Society of Psychologists, a nongovernmental organization whose aim is, among other things, to contribute to the societal engagement of psychologists. She adds that the authorities, when discussing well-being and the pandemic, rarely touch upon mental health.

“We hear about health and economic measures, but there is little empathy and limited talk about how all of this impacts our psychological health,” she explained.

Civil society response

Unlike the authorities, the civil sector is much more involved in providing assistance. Since spring last year at the very start of the pandemic, numerous associations throughout the region have offered help online and by telephone when it wasn’t doable in person due to the lockdown measures.

In Novi Sad, Serbia, a Mental Health Festival was launched in 2016, with the theme, “Chatting at home.” The Festival became even more important with the pandemic.

aThe Mental Health Festival “Chatting at home” became even more important during the pandemic when they offered help online. Foto: Courtesy of the Mental Health Festival.

The Festival is run by a group of the city’s organizations and institutions that have been actively engaged in advocating for improved mental health, and they are currently offering support through email and chat services. The initiative’s coordinator, Marija Rosandić, points out that their services are free of charge and available to all. Their newest feature is a chat service.

“We realized that a chat service is a good solution that ensures anonymity,” Rosandić says. “We can text on our phones, and others don’t need to know about it. If somebody lives in a large family and doesn’t want their family members to hear them talking, this is a good solution,” she explains, adding how, from May of last year until March 2021, the counseling service conducted more than 300 conversations with 96 people through the chat service.

Rosandić says that people come to them with difficulties they face in controlling their feelings; with fears, anger, and the uncertainty they felt during the pandemic. “There was an emergence of a high-level disturbance or even some sort of indifference. That’s exactly one of the strategies for facing stress, some sort of detachment from the situation,” Rosandić tells us.

Research results reveal that people over the age of 65, but also very young individuals, were the ones most affected by the emotional disturbance at the start of the pandemic.

In the meantime, at Novi Sad’s Faculty of Philosophy, a study was conducted under the title “Resilience in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.” The study was launched immediately after the start of the pandemic, in April 2020, aiming to establish the ways in which the pandemic impacts people’s psychological health. Until now, 6,000 people have been involved, with 1,200 to 1,300 participating throughout the research phases.

The results collected until now revealed that people over the age of 65, but also very young individuals, were the ones most affected by the emotional disturbance at the start of the pandemic.

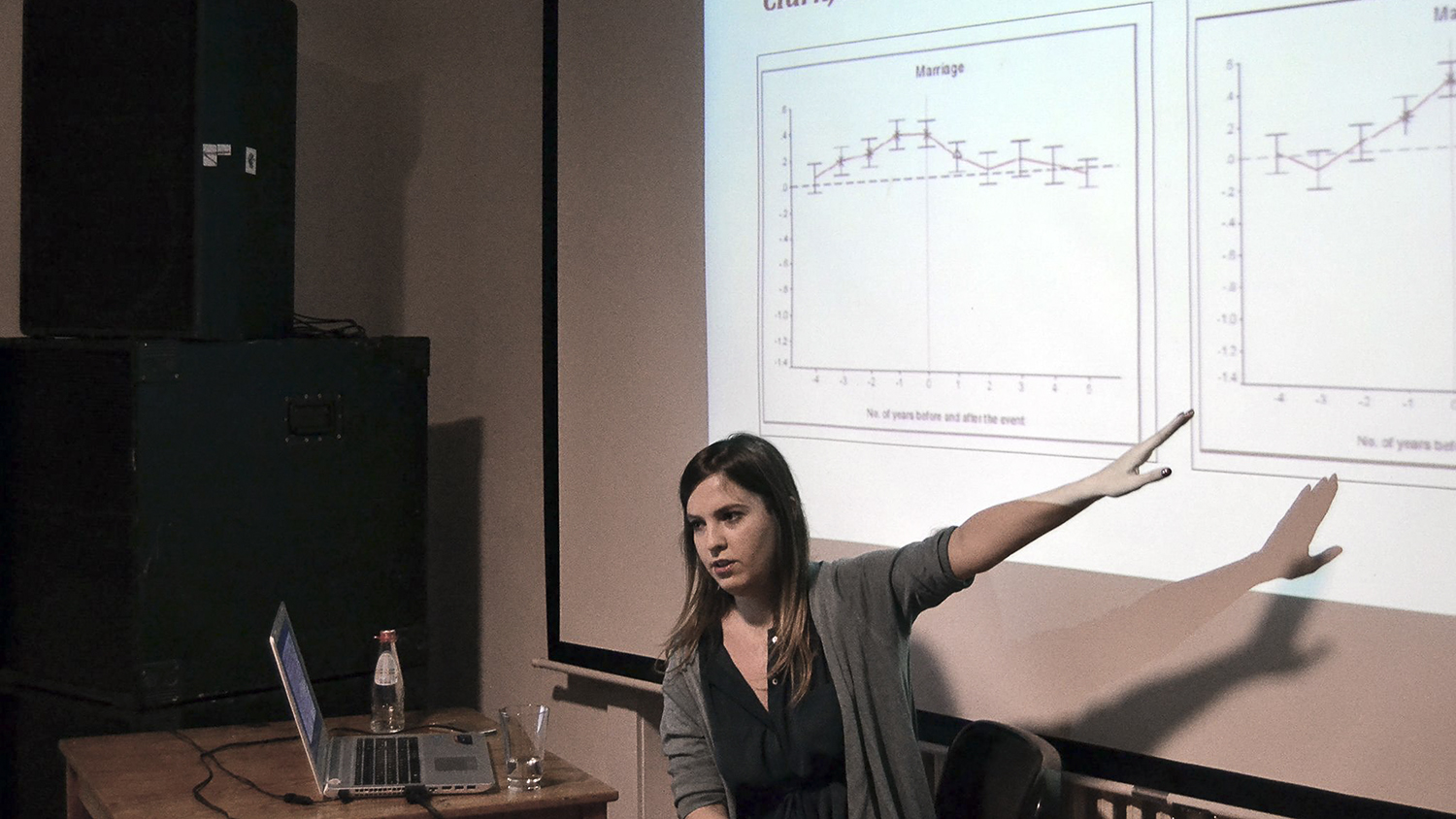

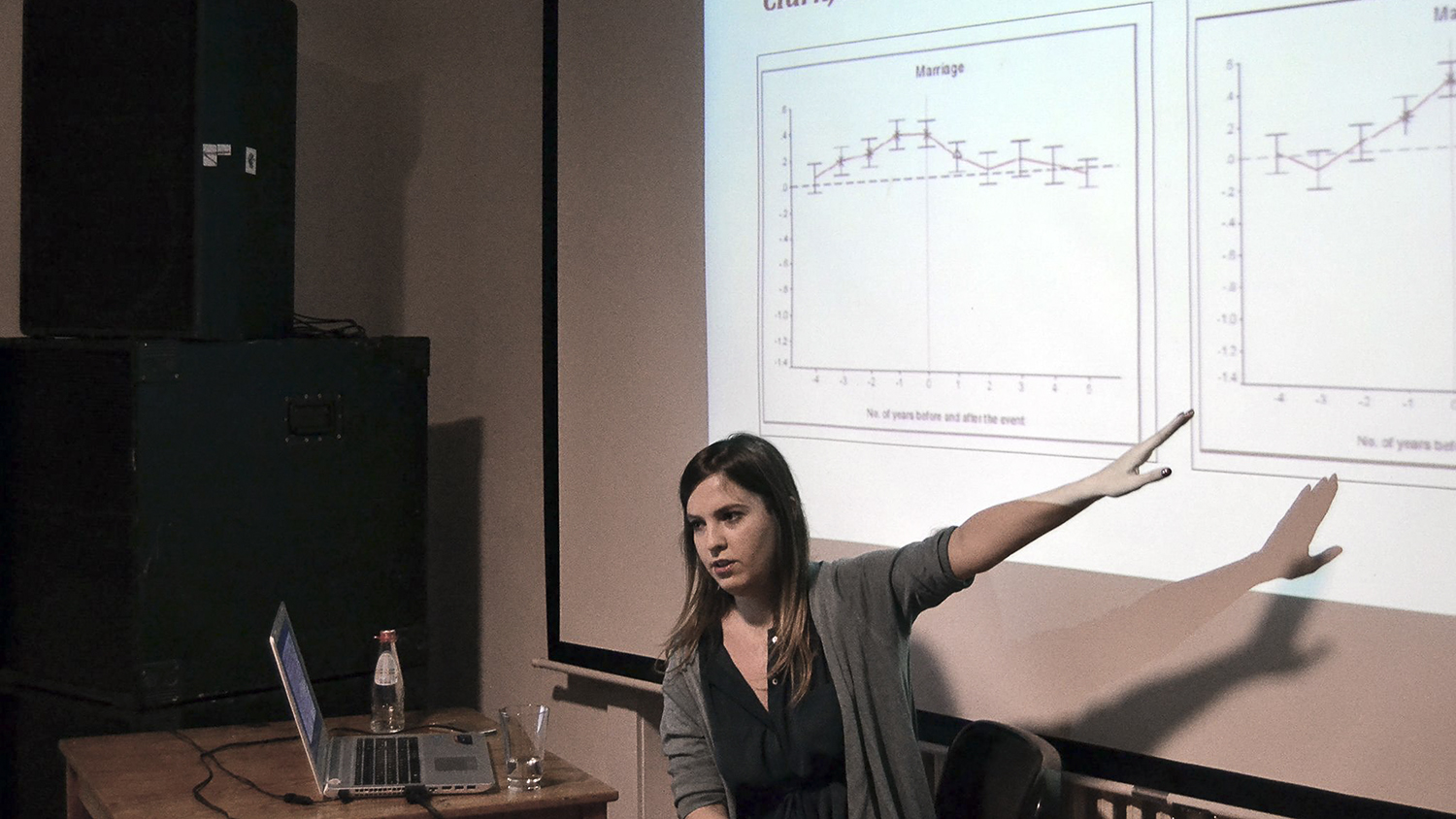

“The generations in between, originally, were the least affected with regard to the change of lifestyle, because they were still going to work, caring for the young and old alike. The lives of the rest of the people changed a lot more,” says Milica Lazić, one of the co-authors.

Milica Lazić is one of the co-authors of the study about resilience in the context of COVID-19 involving 6000 respondents. Photo: Personal archive Milica Lazić.

As the pandemic progressed, per the study results, most people felt a decline in emotional distress, but fatigue has been on the rise.

“At the beginning, when we asked people when they thought the pandemic would come to an end, the majority of respondents said ‘in the next three to six months.’ The lowest was the percentage of those who stated that it would last for more than six months,” Lazić explains, adding that people are disturbed by the notion that we can’t predict the end of the pandemic or know what our lives will look like in the future.

Languishing

Marina Milković from the Zagreb Society of Psychologists notes similar trends and reminds us that only a year ago everybody put all their efforts and resources into adapting to the pandemic. “Health workers were applauded. We subscribed to all the information related to the pandemic, finding ways to adjust to the lockdown. Yet, now we are experiencing fatigue,” she says.

According to University of Pennsylvania professor of management and psychology, Adam Grant, fatigue has been a dominant feeling in his life and environment this year. In an article he wrote on the topic, Grant uses the term “languishing” to describe the entire situation.

“Languishing is a sense of stagnation and emptiness. As if you’re looking at your life through a foggy windshield,” Grant writes in his piece for The New York Times.

Fatigue, uncertainty, and the prolonged duration of the pandemic could have more long term and serious effects for many.

Fatigue, uncertainty, and the prolonged duration of the pandemic could have more long term and serious effects for many. This is especially the case with those who have been completely isolated for long periods of time, as well as older folks and those in a poor financial state. Moreover, neither children nor young people are spared.

“There is also a longer period with frequent online classes, with no trips outside, or hanging out. And, if you miss these things when you are 14-15 years old, you won’t be able to compensate for them when you’re 20,” Milković says.

For Danijela L, whom we talked to at the beginning of the story, this is exactly the aggravating circumstance in handling the pandemic. She says it’s difficult for her to understand that shops and restaurants remained open, while children weren’t allowed to go to school and kindergartens.

The resulting isolation has left serious consequences on young people, as highlighted by the results of a study conducted by the Croatian Agency for Science and High Education; something Danijela herself feels is happening to her family as her own children deal with isolation and few social opportunities.

Conducted with university students, the study showed that half the respondents felt anxiety and depression during remote classes, more frequently than previously. Those affected the most are young people suffering from social anxiety who usually have difficulties managing social situations. A long term lack of socializing opportunities could only worsen their situation.

Among those heavily affected are children and youth living in poor financial circumstances or in large families with no adequate conditions for attending online classes and studying. “Simultaneously, young people don’t even get a simple ‘thank you; what you are doing is important.’ They are often only mentioned as the spreaders of the infection. Even more, information is published about how they are irresponsibly organizing large gatherings,” Milković said.

A trigger for PTSD

It is still unclear what is going to be the long term effect of the coronavirus pandemic on mental health generally. But perhaps the least amount of attention is paid to the impact on people who already carry traumatic experiences from the war and its tribulations during the 1990s, which makes up a large portion of the region’s population.

A study done in Novi Sad had this aspect in mind. Milica Lazić says they looked at previous studies showing how people with past traumatic experiences reacted tempestuously to mildly intense events, whereas others say they survived until now and can withstand this as well.

“We are pretty wiry. But the issue is that we are only surviving and not processing the traumas.”

Tihana Majstorović, Menssana, Sarajevo

However, Tihana Majstorović, project manager at the Association for Mental Health Protection, Menssana, with its head office in Sarajevo, emphasizes that “surviving doesn’t necessarily mean living.”

“Our people are experts in surviving. Our nation doesn’t find it strange to lose a job, to fear for the barest of existences,” Majstorović said.

“We are pretty wiry. But the issue is that we are only surviving and not processing the traumas. All these war experiences have never been processed, which is risky for mental health.” Majstorović also stresses that, despite the experiences of the 1990s, the perception of risk and danger among the region’s people is not necessarily the same as with people who didn’t suffer from the war.

Conducted with 138 people, 11 years after the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina, a long-term study on the psychological consequences of the war indicates a sustained cumulative effect on mental health. This effect is evident in the reactions of people to traumatic events, ranging from disregard to extreme anxiety.

Over 400 people committed suicide in Bosnia and Herzegovina last year (193 in the BiH and 218 in the Republika Srpska).

“I remember when the 2011 terrorist attack against the U.S. embassy in Sarajevo happened. Police were deployed on the streets to keep people back and redirect them. And a woman with a child passed by a police officer, saying that, if they hadn’t killed her in the 1990s, no terrorist would be able to do it now. We have a similar attitude toward the coronavirus, precisely because of the war legacy,” Majstorović says.

She emphasized that Bosnia was the region’s leader in terms of mental health support and PTSD treatment after the war but that there is also a discrepancy between the resources and needs, as well as a lack of knowledge that preventive medical assistance can also be sought.

Association Menssana in Sarajevo organized a number of workshops during the pandemic for its clients, as support. Photo: Association for Mental Health Protection Menssana.

“We haven’t developed a culture of self care before it hurts, seeking preventive assistance; let alone professional psychological help. We only ask for help when the train has already been derailed,” she says.

The grim suicide statistics in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) over the last year and a half confirm her claims. Over 400 people committed suicide in BiH last year (193 in the Federation and 218 in the Republika Srpska), which is 7.9% more in comparison to the previous year in Republika Srpska, and 2.6% more in BiH. Constant anxiety, the threat posed to financial stability and lifestyle, and an utter sense of despair have led to these dismal numbers. The worst possible outcome that a pandemic can inflict on people’s mental health.

Majstorović insists that the pandemic has made a strike against our humanity, the human nature that strives for socializing. She says it’s a highly traumatic experience and explicitly opposes the use of the “new normal” term.

“I believe we must adapt to this situation but also be aware that we have a right to feel affected and bothered by it all.” Majstorović is resolute in stressing that everyone has the right to find the current situation abnormal and to feel that what is happening to them isn’t fair.

Feature photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.