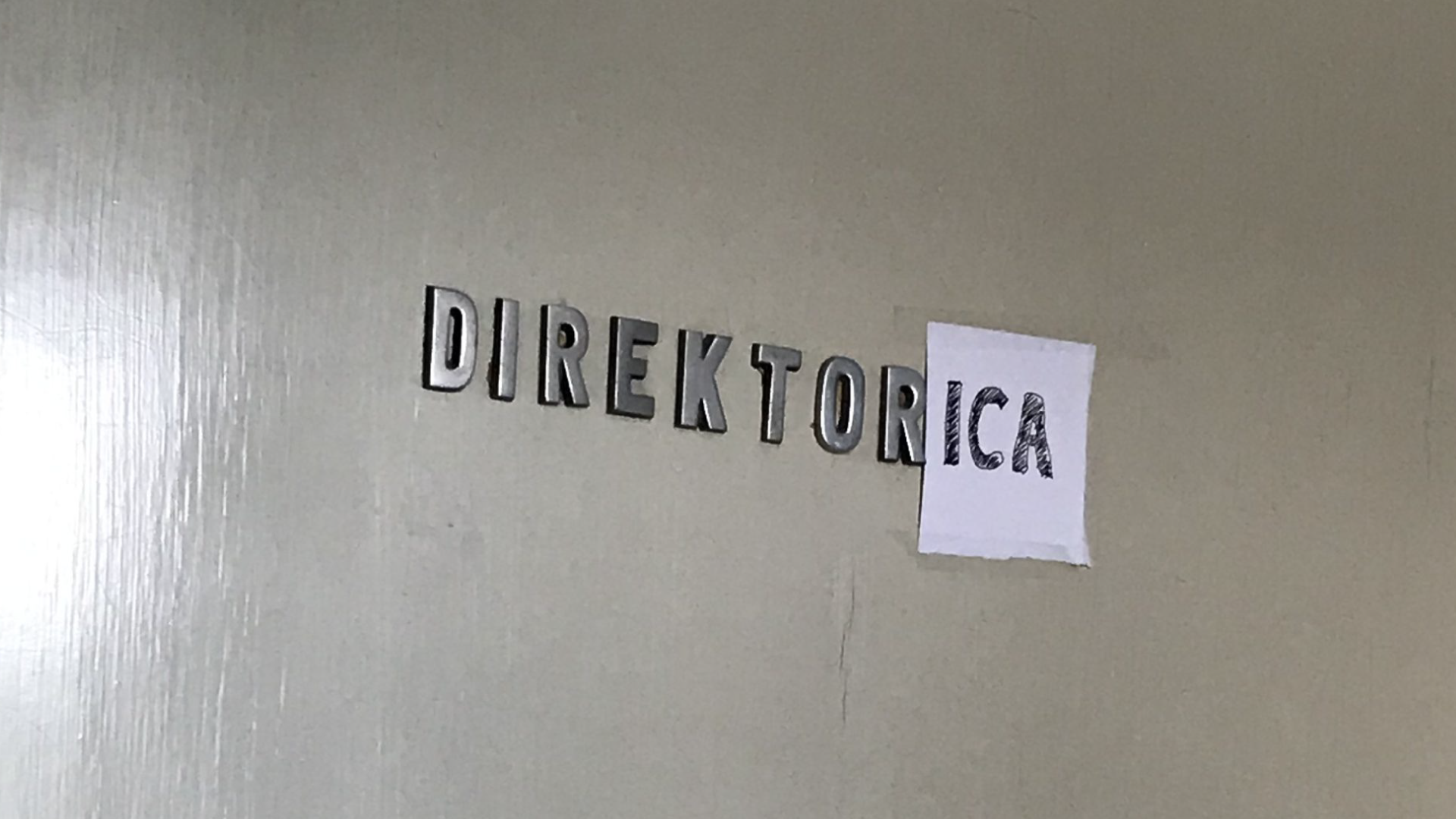

Elma Hašimbegović: We engage with history that is not yet history

talks about the privileges and responsibilities of curating history.

After the war, people had much more optimism and enthusiasm about changing things in a post-war society.

We promote the museum as a place that belongs to everyone.

There is beauty and privilege in following the process of collecting and preserving history.

Nicholas Kulawiak

Nicholas Kulawiak is English language editor at K2.0. He holds a master’s degree in Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies from Georgetown University and bachelor’s degrees in History and Politics from University of Puget Sound.

This story was originally written in English.