At the center of the city of Prishtina there is a monument to revolution. It is rarely thought of as such, but it has been occupying a privileged position for more than fifty years in the capital of Kosovo. If there was a camera on the top of it, it could be the eye of the city. In the Albanian language some people refer to it as “tre rremëshi” (the three branches), or“trekëndëshi,” (the triangle).

According to thorough research by Forum ZFD, the official name oftrekëndëshi is the Monument to Heroes of the National Liberation Movement, and it is dedicated to the fallen fighters who rose up against fascist occupation during World War II. It is located at what is now called the Adem Jashari square, which from its construction in 1961 until the 1999 war in Kosovo was named Brotherhood and Unity Square.

Sources from the Municipality of Prishtina explained to Kosovo 2.0 that the name of the square changed to Adem Jashari in 2000 or 2001, though no document can be found to prove it; the name change was officially re-approved in 2010. The whole space commonly retains the name of Brotherhood and Unity among Prishtinali.

At the end of September this year, the Municipality of Prishtina announced a project to refurbish the square, which will not just clean up the area but also make some changes, especially to the floor of this well trodden public space.

In declarations to Kohavision, Mayor Shpend Ahmeti went as far as to say that he thinks that there should be a referendum to decide whether the central monument of the square, built as part of the ‘Brotherhood and Unity’ philosophy spread throughout Yugoslavia by Josip Broz Tito, should continue to exist in the Adem Jashari Square. “We should either remove the monument or we should change the name of the square; I think it should go to referendum and to the citizens,” he said, suggesting that the current situation of the monument being situated in a square named after an Albanian national hero was a “paradox.”

To add some humor to the issue, Kuku News announced that Ahmeti has asked Adem Jashari to register as a property owner, as there are far too many things in his name — don’t panic, it’s a satirical publication.

But the mayor’s comments caught people by surprise, since a referendum has never been called by the Municipality of Prishtina (at least since Kosovo’s independence); the measure would certainly set a precedent for future decisions. However in this case the discussion surrounding the monument has also highlighted the way in which some perceive this object, often with misconceptions about its history.

The monument to the fallen fighters is considered by experts to be part of the modernist artistic current.

The “trekëndëshi,” was built within the concept of Brotherhood and Unity, Tito’s philosophy for promoting solidarity among the different nations of the federation he presided over. To give to this square the name of Adem Jashari, leader of the Kosovo Liberation Army during the war, to some may sound contradictory, especially if one observes this monument within its original context. * Like many monuments of the Yugoslav era,“trekëndëshi,” is often seen in Kosovo as a symbol of the Serbian repression of the 1980s and 1990s, even though these monuments were originally constructed in a much more peaceful and prosperous period of former Yugoslavia, in the early 1960s, to symbolize everything but confrontation.

The truth is that the future project that will be implemented to revitalize the Adem Jashari square will not touch the monument to the fallen fighters. This project doesn’t contemplate the removal of this monument, but the discussions raised after the presentation of the project and the comment of the mayor have given space to many questions. What was there before the square was built? What did the authorities of the time intend with this construction? What does it symbolize, within its context? Does it have protected cultural heritage status? What is going to happen to it now?

Let’s look at the entire picture.

Destroy the Old, Build the New

The same surface where today we find the Adem Jashari square and its central monument was previously part of an authentic cradle of life and part of the center of the old city of Prishtina. Part of the old bazaar (divanjolli or çarshia, in Albanian), existed at this surface in the form of several shops and buildings of traditional and vernacular architecture. There also used to be a local road connecting the area of today’s old town and the still existent (but dysfunctional) railways at the doors of the Arberia neighborhood. This picture would start to change dramatically, especially after 1947 when Prishtina became Kosovo’s capital city.

To the slogan of “Destroy the old, build the new,” many old-bazaars and constructions that represented old Ottoman architecture (among other types), were destroyed across Yugoslavia to bring a new landscape in the name of modernization.

Before 1960, the the site where we today find the Adem Jashari Square was part of the old city of Prishtina.

At this space, on either side of the road that no longer exists, two modern buildings that represented a new architectural style started to be erected: a provincial building that today hosts the Assembly of Kosovo, designed by one of renowned Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier’s apprentices, and a municipal building, the current Municipality of Prishtina.

Kosovar architect Rozafa Basha explained that the justification used for the destruction of the old bazaar was that it was made of old and weak construction materials, so authorities wanted to build something new, and decided to use the area to establish new institutions. But Basha suggested that there were also ideological factors at play. “The decision [to destroy the old bazaar] didn’t only have to do with poor structures,” she said. “It was also about bringing a new way of living.”

In a text written by another architect, Eliza Hoxha, for a report on Prishtina’s cultural heritage, the author states: “A new socialist order had to bring a new city which had to be in harmony with other urban centers of Yugoslavia.”

On the Path to Brotherhood and Unity

The square of Brotherhood and Unity, together with its central monument, was a project designed by Miodrag Zivkovic, a Serbian sculptor known for his memorials across ex-Yugoslavia. Eventually he was also the dean of the Faculty of Applied Arts within the University of Belgrade in the 1970s and again for some years in the 1990s.

Zivkovic was born in 1928 in Leskovac, southern Serbia, a city of more than 60,000 inhabitants; its borders connect with Kosovo’s borders. Architect Rozafa Basha explained to Kosovo 2.0 that the monument to the fallen fighters in Prishtina is actually the result of a contest. In 1959, Zivkovic was the winner of a national competition to design a monument to revolution for the city of Prishtina: the Brotherhood and Unity Square.

The ideal of Brotherhood and Unity gave name to many schools, venues, and pieces of public infrastructure, including the main national Ljubljana-Zagreb-Belgrade-Skopje highway. In Prishtina’s concrete square, this motto was mixed with another cause: to pay homage and tribute to the fallen fighters of the anti-fascist war — no matter from which ethnicity they originated.

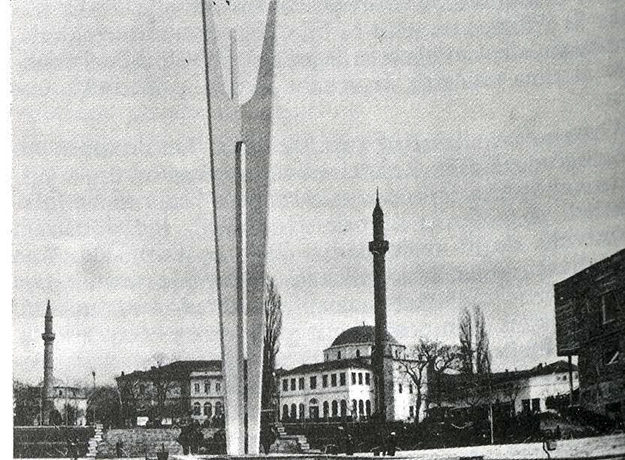

At the center of the 160 square-meter sheshi, the monument consists of two parts: a 22-meter high obelisk with three poles that open like a bouquet and a sculpture portraying eight Partisan figures placed ten meters in front of the obelisk. Shortly after Kosovo declared independence, a group of students painted these Partisan figures to represent the flags of Western countries that had supported Kosovo’s plight.

An image of the monument from the 1970s.

Initially there was a fountain on the other side of the obelisk, opposite the Partisan figures, although this disappeared as part of modifications in the 1970s. Not much else has changed throughout the decades at this space in terms of its aesthetics, which fall into the modernist current. The whole picture has become an iconic image of the city; a meeting point for youngsters and an area to hang out for diverse groups of people, but especially for kids since the installation of a skate-park in one of its wings.

Vanishing Values and Editing History

In 1999, after the NATO intervention in Kosovo, the monument suffered an attempt to damage it with dynamite, the long-term effects of which have yet to be fully analyzed. Again in 2010, the previous administration, led by current Prime Minister Isa Mustafa, also attempted to knock the monument down. The plan included an underground parking lot and the erection of a statue of Adem Jashari but the project failed to materialize.

But the attempt to destroy this monument wasn’t unique. The political developments in the whole of Yugoslavia after Tito’s death in 1980 presented a drastically different context of increased hatred and confrontation between nations. In Kosovo, the repression of Albanians, especially during the ‘80s and ‘90s, saw a backlash against monuments from socialist times, including the memorials of the National Liberation War.

In an article written by Shkelzen Maliqi for the publication “Monument, the Changing Face of Remembrance,” the author says: “It seemed as if Tito’s ideology and promise for brotherhood and unity practically vanished overnight.”

Art historian Vesa Sahatciu has undertaken in-depth research into the tradition of these monuments and believes that perceptions of Yugoslav-era monuments as Serbian are misplaced. “The monuments from the Yugoslav period should be looked at from the historical context that they came out of,” she said. “To reduce the debate along national lines is to give these monuments a meaning they did not originally have.”

Sahatciu believes that the monument is important for its artistic values and as a reference to a certain historical period. She also acknowledges the fact that these Yugoslav-era monuments were built, in her words, “to channel the socialist ideology of the time.” All in all, the art historian concludes that “to get rid of these monuments is to opt for collective amnesia.”

Cutting up the Grass

To understand what the latest plan is for the Adem Jashari Square and its central monument, Kosovo 2.0 talked to the architect that has overviewed the design of the renovation project, Gyler Mydyti, an external municipality consultant from the United Nations Development Program. The project, which Mydyti says is an initiative from the mayor, has absolutely no plans to remove any part of the monument to the anti-fascist fighters, nor the obelisk, nor the sculptures at ground level.

“The mayor wanted more green spaces,” said Mydyti. She explained that this square has only gone through revitalization twice in more than three decades. In the end, the result of the design is an increased surface of green, which will be integrated with a redesigned floor.

The latest project designs by the Municipality of Prishtina.

The architect explained that the stairs located on the side of Agim Ramadani’s street will change, though a central part of them will remain with the same style in order to pay homage to a professor of the Faculty of Architecture, Burhamedin Sokoli. According to the architect, this professor always said in his lessons that the square is an example of how not to design stairs; they are too long for taking one step at a time and too short for including a second pace.

The new design includes a change of the floor, stairs and more green areas.

As with many constructions from the Yugoslav era in Kosovo, neither the central monument or the square enjoy the designated status of protected cultural heritage. All the architects consulted by Kosovo 2.0 agreed that the area is technically regulated as part of a ‘buffer zone,’ due to its proximity to the the Historical Center of Prishtina, the limits of which are only a few meters away. A buffer zone is the area in the close surroundings of a site that enjoys protected cultural heritage status. However the Historical Center of Prishtina currently only has temporary protected status; as yet, there is no conservation plan to oversee the development of either the protected area or its perimeter surroundings, including the Adem Jashari Square and its Monument to Heroes of the National Liberation Movement.

Whether the monument will be removed or not in the long-run — with a referendum or without it — remains a decision of the Municipality of Prishtina.K

Photocredits: Archive images and design of the project courtesy of the Municipality of Prishtina.

Facebook and Homepage illustration by Driton Selmani.

*Editor’s note: In the previous version of this article, K2.0 overlooked the sentence “To give to this square the name of Adem Jashari, an ethnic-Albanian and so-called hero of the 1999 war, may sound contradictory, especially if one observes this monument out of its original context.”

On November 6, 2022, K2.0 corrected this so that the sentence and the article better reflect the facts.