Between three other constructed worlds from Indonesia, Lebanon and Ireland, the pavilion of the Republic of Kosovo opened its doors yesterday at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition (or Biennale Architettura 2018), after an absence in the 2016 edition. Surrounded by a large number of high level Kosovar dignitaries, Eliza Hoxha, the curator of Kosovo’s “The City is Everywhere” pavilion, introduced the global architecture community to Kosovo’s parallel history of the ’90s.

Like any story of parallelisms, many dimensions were created inside this particular shoebox, determined to challenge the concept of this years’ Biennale: freespace. From the outside, the Kosovo pavilion appears demarcated by a large orange-ish brick wall up to the edge of the Arsenale venue’s ceilings, a reminiscence intended to recreate the external façade of many of Kosovo’s unfinished houses.

In the ’90s, private homes often acquired unplanned functions as a result of Slobodan Milošević’s attempts to exclude ethnic Albanians from public life by expelling them from public institutions like schools and hospitals, and establishing a climate of repression. This pushed the majority of Albanians outside of the public space, the city, and towards the safety of the home.

Inside the pavilion, a tale of psychological freedom and physical blockade begins. The inner walls of the Kosovar pavilion play with the mind of its visitors — the image of one single visitor is replicated dozens of times in the mirrors installed as walls from ground zero to ceiling. It gives the sensation of a multitude within the space, on the one hand, a crowd typical of a city, and on the other, the sensation that the space is unlimited and never-ending.

Above one’s head, 72 satellite dishes function as an umbrella ceiling. A symbol of life in Kosovo during the ’90s, the satellite dishes remind anyone who experienced this period in Kosovo of the two-hour Albanian news that would gather neighbors and relatives in front of the TV, the importance of MTV possibly more than anywhere else, and the value of information. An entrance point for citizens to understand what is happening outside their homes, and an escape point to connect with what is happening in the rest of the world.

The pavilion team aimed at having all satellites donated by citizens, however this was not possible as not enough personal satellites were given to the cause. Brand new dishes were installed instead, each carrying the name of those that donated a satellite and the names of people hosted in their homes. The dishes collected so far, explains a member of the team, remain saved for a potential future project digging again into collective memory.

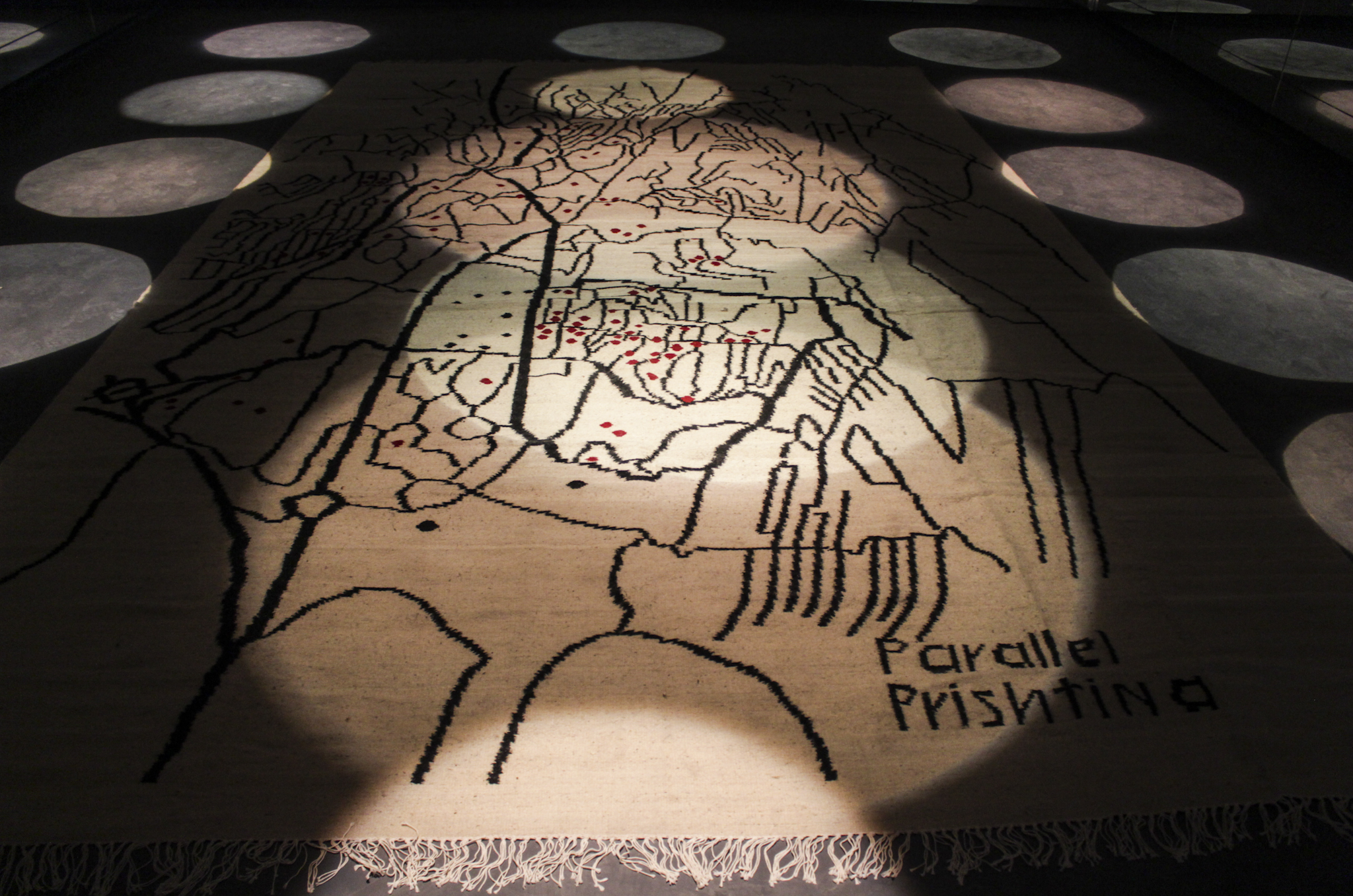

On its floor, the pavilion features a single central element, a traditional-style carpet of “Parallel Prishtina” woven by women from the region of Has. The carpet, which displays a map of Prishtina, identifies in black the roads and official public institutions from which Albanians were expelled. In red are the hotspots where university classrooms were hosted in private houses. The contrast in colors demonstrates the separation of the city at the time, with the center a sea of black, while the red is dotted around suburban neighborhoods like Ulpiana and Arberia.

Spaces of collective memory

For Kosovo’s first representative at Biennale Architettura in 2012, award-winning architect Perparim Rama, the pavilion connects with his subconscious and leaves behind a strong impact. “This eternal and continuous space and the satellite dishes hovering above me kind of connects me to my ’90s, my childhood,” says Rama, who spent two years in Kosovo during this decade. “The experience was very similar to what you experience in the Kosovar pavilion.”

For the London-established architect, the theme of the pavilion comes with meaning. “It’s a very recent history where Albanians in Kosovo were literally imprisoned,” he says, “or they were free in private, so there was this sort of inverse condition.” In this inverse condition, says Rama, “the moment they stepped outside, they were no longer safe, so the public space was the prison.”

Mind tricks aside, the pavilion brings back to the present a piece of history that remains to this date much under-discussed, under-documented and neglected by institutions and society at large. The Kosovo pavilion focuses on the overall parallel dimensions created within the city using the house as a metaphor, with a special spotlight on the parallel system of education.

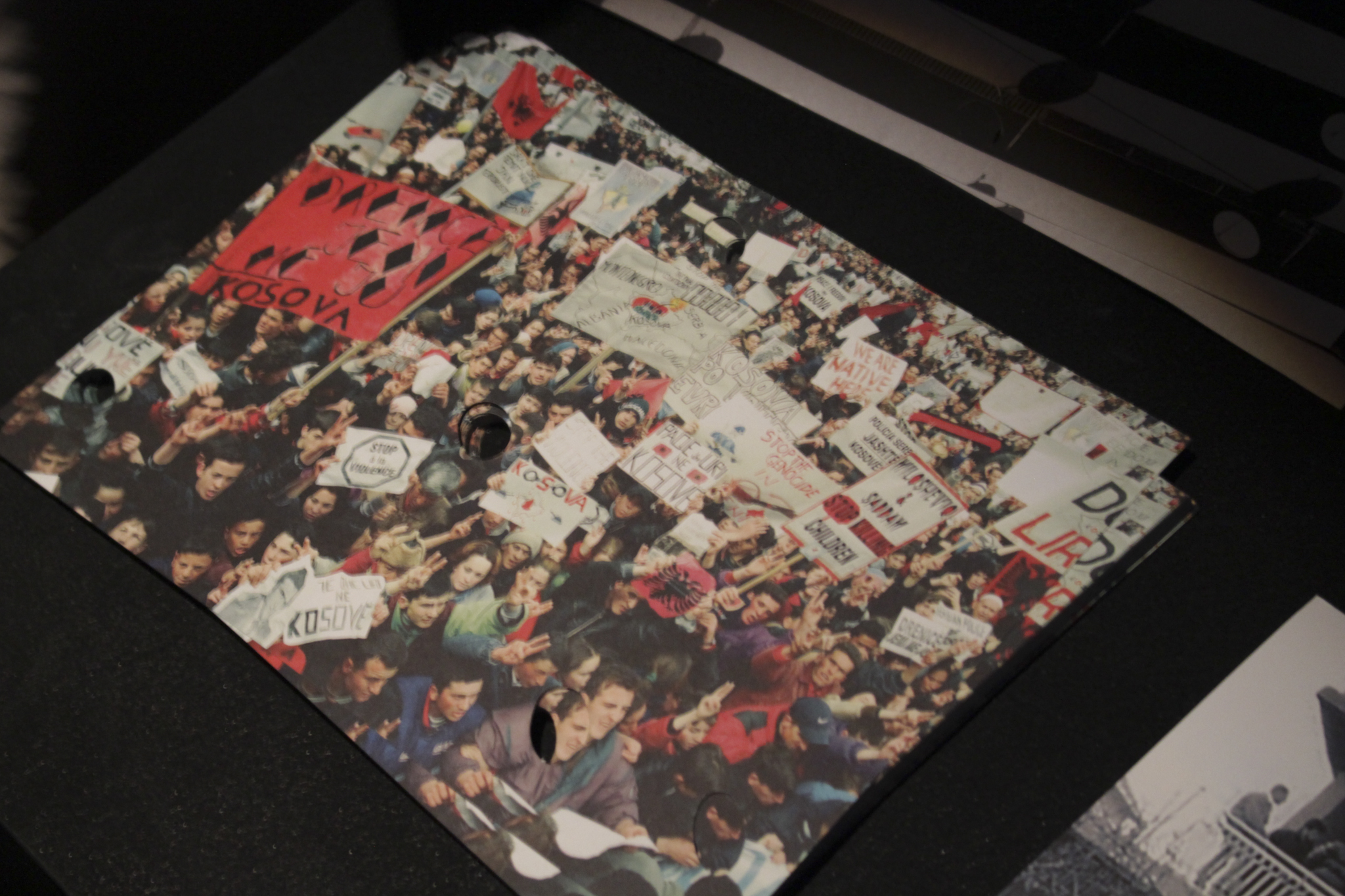

In September 1991, having already removed many Kosovar Albanian teachers from their positions and imposed Serbian curricula, the education system in Kosovo was entirely shut down for Kosovar Albanians. As K2.0 reported in its “’90s” magazine, an estimated 21,000 teachers lost their jobs and around 400,000 students from elementary school, high school and university level were denied the right to pursue their education in public education institutions.

Beyond the physical project in Venice, “The City is Everywhere” also includes a number of complementary works that aim to elevate the impact of the pavilion beyond its presence at this prestigious event. As part of it, a book will be produced offering complementary texts based on the experiences of different citizens in Kosovo. The book will also include the results of research aimed at mapping out the private houses and private spaces which hosted university classrooms across Prishtina.

Among the researchers involved was Ardita Byci, an urban planner and professor of the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Architecture. She herself was schooled during her first three years of university in the parallel system of education.

Byci remembers well how despite studying in private homes, professors were highly committed to carrying on with normality. “Once a friend was late to submit a project because she was stopped by police in the street and the professor did not accept the paper, even in those circumstances,” she says with a bit of nostalgic resentment. “It’s just an example of how committed they were to not changing the rules they would have in a normal classroom — to keep the same level you would get in a school.”

For Byci, who contributed to the research for the pavilion and provided a text for the accompanying book, the university offers a connection that no other space possibly did. “During the 70s, after the university was created, it was received as a big achievement and became a strong bridge, and a motor of dynamic life between residential spaces and the public space,” she explains.

She refers particularly to the campus of the University of Prishtina, which unlike many other campuses in the world is located in the very center of the city. “When the university was stopped in the ’90s, a motor of culture, education and social life was stopped as well.”

Despite this cessation, Byci believes that the light brought in by this single motor was transformed into multiple motors across the city. She brings up the theory of renowned contemporary design theorist, Christopher Alexander, who argues that universities throughout cities instead of isolated campuses are far richer. “We were doing that all along…” Byci says, half joking, half not.

Psychological freedom, a replacement for visa

The pavilion’s curator, Eliza Hoxha, referred in her speech to the Kosovar public officials present, who included in their number: Minister of Foreign Affairs, Behgjet Pacolli; Minister of Spatial Planning and Environment, Albena Reshitaj; Minister of Culture, Kujtim Gashi; President of the Kosovo Assembly, Kadri Veseli, and other representatives such as the Kosovar ambassador to Italy, Alma Lama, and the commissioner of the pavilion herself, Jehona Shyti, who acted as master of ceremonies.

Veseli took this particular opportunity to state that: “[Kosovo] will not remain in isolation, Kosovo does not need satellites anymore, and we expect that from December we will have visa liberalization.” However, the green light from the European Parliament has yet to be given and no dates for visa liberalization for Kosovar citizens have officially been set by the European Union.

Isolation caused by visa liberalization is also an issue which the curator aimed to address in her work. Speaking to K2.0 before she left for Venice in a wide ranging interview, Hoxha said: “In Kosovo today you are free in many ways but you are not able to move.”

In her presentation speech in Venice, Hoxha put a focus on the many under recognized roles played by citizens of Kosovo in the ’90s and the need for public discussion. “If it wasn’t [for] these schools I wouldn’t be here,” Hoxha said addressing the assembled public officials, collaborators on the pavilion project, the community of architects from Kosovo present at the event, and other curious visitors. “It’s been difficult to collect these untold stories and this is a crucial time to speak about this topic. It is time we speak about this story, 20 years after, and confront it.”

Speaking later to K2.0, Hoxha also stressed that it’s now time for government action. “We did it all in the ’90s, we didn’t have a government. Now it’s time for the government to recognize the ’90s and to support this story to be told for others.”

For Hoxha, the Biennale, as well as other large cultural platforms, such as Cannes, are important for Kosovar society but she also highlights the fact that she is the first Kosovo-established Kosovar to ever represent the country on such a large platform.

“Everybody who [has exhibited at] the Biennale are Kosovars living abroad and it’s really okay because you can ensure that it will be a success, because they are successful – Petrit [Halilaj], Flaka [Haliti], Perparim [Rama], Gezim [Paçarizi], Sislej [Xhafa],” she says. “[This is] the first time that someone from inside was given this opportunity. They are all Kosovars and contribute to the Kosovo story, but we have to give opportunities for the people who decided to live in Kosovo and don’t have opportunities abroad. This is an open door for others.”K

Feature and image and video: Cristina Marí / K2.0.