Arbër Qerka-Gashi began by posting old family photos to the Balkanism Instagram page in April 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic. What started out as a personal project now has amassed almost 50,000 followers, and covers a range of topics — clothing, food, history, contemporary social issues and more — pertaining to Balkan countries and peoples.

Balkanism defines itself as a “cultural, historical, social, archival, educational collective and publication” that seeks to improve interethnic relations in the Balkans and among diaspora communities. It aims to do so by profiling traditions and communities that have often been overlooked or actively marginalized.

Balkanism’s following grew rapidly in July 2020. Qerka-Gashi, a 27-year-old writer and curator born in London to Kosovar Albanian parents, published a post urging Apple Maps to include Kosovo. The post went viral and was shared by pop star Rita Ora, who in turn tagged other stars like Dua Lipa, Bebe Rexha, Ava Max and more. Qerka-Gashi’s original post now has over 100,000 likes.

Balkanism’s clear support and advocacy for Kosovo have drawn the ire of online Serb nationalists, who relentlessly targeted Qerka-Gashi in online attacks. Qerka-Gashi has also come under fire from extreme Albanian nationalists objecting to Balkanism’s vision of being a pan-Balkan rather than exclusively Albanian page. Nonetheless, he has forged ahead with the page, driven by his desire to continue cultivating a transnational and transpatial community around shared and unique Balkan identities.

On September 28, 2024, Qerka-Gashi launched Balkanism’s first physical publication, “Diversity as Strength,” at the Migration Museum in London. It features 50 contributors from throughout the region and its diasporas.

Qerka-Gashi, Vujinović and other members of the Balkanism community have also turned momentum from the online page into physical events in the form of the Balkan London Collective, which has hosted two Balkan Prides as well as discussions and film nights. Such events seek to create an inclusive, progressive space in London where various Balkan identities can be shared with one another and celebrated.

K2.0 caught up with Qerka-Gashi, who has also written for K2.0 in the past, to discuss the challenges of moderating an online platform about a region whose inhabitants haven’t always seen eye-to-eye, producing a print publication and the joys of bringing Balkan diaspora communities together in person.

K2.0: Can you tell us a bit about where you come from and what brought you to start Balkanism?

Arbër Qerka-Gashi: I was born and raised in London to Kosovar parents who moved before the war, in ‘93 or ‘94. They saw that the situation was escalating in Kosovo and felt the need to move.

Both my parents were born in Prishtina. My mum comes from a Turkish-speaking family from Prishtina, and my dad comes from an Albanian family originally from the Llap region [in northeastern Kosovo] with a deep history of agriculture and farming, whereas my mother’s side is very connected to the urban space.

I grew up in East London. My experience growing up in Britain was very confusing. Kosovo was never really represented in any way, shape, or form. I felt a real sense of confusion regarding my identity but also really not having any external space to explore. I also saw, through social media, a lack of progressive Balkan spaces that dealt with identity and the complexity of being from a region like the Balkans.

I studied for my bachelor’s at Goldsmiths [University of London], which at the time had a cultural research center for the Balkans. That pushed me to study there even more. I specialized in the former Yugoslavia, specifically Kosovo within the former Yugoslavia. I finished university and then COVID hit in 2020 and I found myself sitting on a lot of resources and information I had acquired through the years. My parents also gifted me a lot of their archival photos.

I think Balkanism is really unique in the sense that a lot of Balkan spaces on social media are dominated by Bosnia, Serbia, Croatia.

I felt the need to start archiving them but also to use these images and knowledge to start a platform that was super progressive and dealt with issues of Balkan identity that have never really been explored before. I think Balkanism is really unique in the sense that a lot of Balkan spaces on social media are dominated by Bosnia, Serbia, Croatia. As somebody from Kosovo, I really wanted to be able to provide a different narrative and provide a different space, especially from a Muslim perspective, a Kosovar perspective. The complexity of my family’s ethnic identity, as well, is something that I really wanted to see explored in a more authentic way. That was what birthed Balkanism.

What was your initial vision for Balkanism? Has that vision evolved over time?

My initial vision was definitely more personal and focused on my relationships. Like I said, my mom has a complex identity, my dad has a complex identity. They grew up at a time when Kosovo was an autonomous province in the former Yugoslavia and people in Prishtina experienced Yugoslavia in a very different way to other parts in Kosovo, especially the rural spaces. So I was raised with multiple cultural influences. I have Turkish influence, Albanian influence and Kosovo influence. And then, there’s the Yugoslav, Balkan influence that really impacted me culturally.

It also allowed me to connect with a lot of different people. I would connect with people from former Yugoslav countries because we ate the same foods and we used the same products. I would connect with Albanian people because I speak Albanian and I’m Albanian. I would connect with people from Turkey. I saw myself in a broader Balkan space and being connected to so many different countries. But also due to my own family history, I’ve got a lot of family dispersed in the region. I’ve got family in Turkey, Macedonia, Montenegro and Bosnia due to various socio-political factors. Balkanism was founded with my own relationship with the region in mind.

Balkanism as a term was coined by Maria Todorova, an academic who spoke about the Western world’s relationship with the region. It was born out of Edward Said’s “Orientalism.” I wanted to reclaim Balkan identity and explore it in a way that is a bit more authentic.

Balkanism engages with communities in the Balkans and in the diaspora, and seeks to build links between different Balkan diaspora communities. Photo: Kairo Urovi

The Balkans are often represented as trumpets and folk music within Western spaces. It can be really unrepresentative. That was something that really fueled me to actually start exploring cultural elements about the Balkan region. I just wanted to make sure that this was a progressive space based in transitional justice, deep conversations and authentic cultural presentation.

How do you think your diaspora positionality informs your work? Are there any particular drawbacks or advantages that come with this perspective?

The fact that I was born and raised in London massively impacts how I perceive the world. I grew up in a very ethnically diverse, multicultural space and environment. It’s something I see as a great value. When I’ve studied Kosovo’s history, I’ve recognized a lot of ethnic diversity and multiculturalism, but something I really want to make sure that I’m not doing is romanticizing or perpetuating this kind of Western-liberalesque approach to ethnic inclusion and diversity because that is something that often happens, especially through EU-mediated initiatives, especially in Kosovo.

It’s something that sometimes I feel people use against me. They’re like, “you live in the diaspora. You have this completely different experience.” But I really make sure that when I’m writing a caption or I’m presenting some information, I say that I am from the diaspora. I have this perspective and I don’t have a lived experience of being raised in Kosovo. I visited over the years, quite substantially, but my experience and relationship to Kosovo is formed through my parents’ experience. I make that quite well-known through the platform.

I’ve also wanted Balkanism to be a very open space. Obviously, I’m not going to be able to know everything about Kosovo or the region, the vastness and the different cultures and identities, so when I don’t know something, either through stories or a caption, I urge people to inform me.

It’s been precisely that process of being open to criticism that has allowed us to develop the way we’ve produced content and represented communities. I’m open about the fact that I’m not born or raised in the region. I understand that. But I’m also deeply connected to the region, historically, ethnically and culturally.

The thing is a good portion of our audience is diaspora-based as well. I think that a lot of people in the diaspora have wanted this space to exist. With that being said, I also don’t want to exclude people in the region because, of course, they are part of this conversation.

Given the many perspectives in the Balkans, how do you keep it a safe and inclusive space?

In 2021, I started a Balkanism working group. I put out a call for ambassadors. These were going to be content creators for the platform, from diverse and different perspectives in the region. It was almost like an employment process.

We got 85 applications or something like that. I was the only one doing it at the time, so I had to go through an extensive interview process with them to ensure that their values matched up to what Balkanism was trying to do. Currently, we have a working group of around 13 people. It’s a group of people from different identities and experiences and it includes both diaspora-based and Balkan-based. I wanted it to be a community-based space.

As the page grew, I saw the necessity to make sure other voices and narratives were being included. If you go to the platform, a lot of the content that’s being made is by people from specific identities. I think the necessity is to see their own voices and their own culture represented in the best way that they know how, because I obviously speak from my own individual perspective. That’s how we’ve made sure that we’re holding ourselves accountable.

How does the content curation process go?

I like things that are quite visually appealing. I go through archives and different mediums to find content and material that works for the page. What is quite unique about Balkanism is that we touch on such a wide range of themes and experiences stretching from cultural, artistic photography based, to social rights issues based. A multitude of narratives can be explored on the platform. I think that’s something that really draws people in. I’ve been asked “what’s your target audience?” It’s pretty much everyone.

What have been some of the challenges in moderating content and managing community feedback?

In the beginning, it was extremely volatile. Initially, the platform was very focused on my own relationship with the region and these beautiful photos. But I think it was July [2020], I saw that Palestine was not included on [Apple] Maps. When I looked at Kosovo, I saw it was also not included. I felt the necessity to produce some type of content focused on representing the fact that Kosovo does exist and making sure it was being represented in the best way possible.

I made a post saying “put Kosovo on the map” and it became this massive trend that went super viral. Rita Ora, Dua Lipa, Bebe Rexha, all of them were promoting it. Then I received a lot of backlash from ethnonationalist Serbs attacking me. There was this whole desire to dox me and find who I was, where I was. Death threats, a lot of death threats.

Balkanism came to online prominence when Rita Ora reshared a Balkanism post that called for Kosovo to be included in Apple Maps. Photo: Modified screenshot of Facebook post by Rita Ora.

That was really difficult because we were in COVID. I was stuck at home with my family. It was equally quite incredible because there were even posters printed out of the post I had made in the middle of Prishtina. My cousins sent it to me, saying “look Arbër, you’re in Prishtina,” and my Slovenian friends showed me Slovenian news reporting on it. It was such a crazy time, but equally really difficult because I was dealing with it myself, having people attack me quite harshly.

Then, super ethno-nationalist Albanians were accusing me of being a traitor for wanting to run a Balkan-based page. There were a lot of Albanian and Serbian groups that would attack me and be super problematic and really volatile, with a lot of really disgusting language. It carried on quite consistently through 2020.

Block is a fantastic feature. So I just kept blocking people while also being quite consistent with posting, because I saw a lot of people who wanted me to stop the platform.

It was really difficult. I think I expected it from the ethno-nationalist Serbs. The conversation about Kosovo becomes super tense, but having it from members of my own community was really difficult because I was backing and supporting Kosovo as an independent state. And outside of this, in my own endeavors, I’ve received a lot of critique for the positions that I hold, and for the identity that I have, as somebody who’s from Kosovo.

We went from 300 followers to 10,000 in a couple of days, which was quite crazy.

But I think I’m quite Albanian, in the sense that I’ve got the desire, I’ve got the passion and when I’m onto something positive, I feel like I need to continue it. So I continued with the work. We went from 300 followers to 10,000 in a couple of days, which was quite crazy. But we’ve had sustained growth. We’re nearly at 50,000 followers four years down the line and that’s something that we have done organically.

The thing is that critique is fine. I’m not against critique when it comes to ideas and theories. And I know that my ideas and my approaches are massively impacted by my own personal lived experience, by my family’s lived experience and by the research that I’ve done. Sometimes, especially through Albanian social media and through Balkan social media more generally, if you don’t fit a certain narrative, you are completely chastised.

But four years later, I’ve come to deal with it quite well. At Balkanism now, thankfully, touch wood, we don’t really receive any volatile comments. I think they know they’ll just be removed.

How did launching Balkanism’s first print edition go? What were some of the challenges you faced during the process?

It was definitely a very stressful experience. For the last two years or so, I took writing more seriously. I was included in a bunch of Britain-based magazines and publications online and in print. I got the bug. I love independent publications. I had the idea maybe three, four years ago to have my own publication of sorts, but I was studying for my master’s at the time, so I didn’t really have any time.

The designer of the magazine is Verica Petrović. She’s a book and magazine designer based in Serbia. We became really good friends through the page and she started working on Balkanism as a lead ambassador. She took the initiative to make a mock Balkanism magazine, maybe two years ago, as a part of a university project and it came out super beautifully. That’s where the idea was born: a publication that deals with Balkan identity and represents Balkanism in an overall sense.

Balkanism’s first print magazine featured a striking photo of a Kosovar Roma woman, taken by Janet Reineck. The magazine was designed by Verica Petrović.

Last year, I was going through multiple different avenues trying to secure funding and gain as much experience as possible before producing the product. Sadly, securing funding for a project like Balkanism proved to be very difficult, because we hold quite strong positions, especially politically and socially. And I feel like a lot of people are just a bit weary when it comes to dealing with the Balkans in that sense. Earlier this year we put a call out for contributors. I had also commissioned about 11 people to write essays, articles and photography. We had, maybe, over 100 submissions of artwork, pictures, all these different things. If I had the budget I would have included them all.

Funding was the issue. I wanted to contribute my own funds into it and was very privileged to do so. But we also went through a crowdfunder campaign: from April to June [2024], we launched a Kickstarter through Balkanism and we were able to raise 4,200 pounds [roughly 5,050 euros]. It was really incredible and amazing that people wanted to contribute to Balkanism.

Verica started designing around April [2024]. It took about four months, because we were liaising with so many Balkan people in the region, in London and all over the world. A lot of people were not on time, which is very understandable and expected with independent publications. We finished it fully in late August and went to print in September.

I am thankful to have the cover. I had seen this image, maybe, four years ago. Janet Reineck [who took the photograph used for the cover image] researched a lot about Kosovo and the ‘80s and ‘90s. We gained a really good relationship and I found her archive online. I really wanted to use this image front and center because it depicts a Kosovo Roma woman with traditional hand henna. I thought it was such a striking image.

In the publication, we deal with a range of themes related to race, ethnicity, sexuality, gender identity, people from the diaspora, people from back home, issues to do with being a minority in a majority-other ethnic country and other facets and experiences. It depicts communities and cultural practices that are really not represented within Balkan spaces. The initial reception has been super positive.

Aside from Balkanism’s online community, you’re also involved in the Balkan London Collective, which hosts events, parties and Balkan Pride. Was it important for you to have the Balkan diaspora community interact in-person?

Definitely. Balkan London Collective came into existence due to relationships I created through Balkanism. Tamara [Vujinović] is the co-founder. We had known each other for two years. She had been already doing Balkan-related events in London, book events, panel events. She had this really good relationship with a cafe in London Bridge [an area in London]. She would do these events on a regular basis and I communicated with her that we need something else. We need something more for Balkan LGBT people and Balkan people more generally to engage in a progressive space.

And so there was a real necessity to make sure that we were creating and curating spaces for all Balkan people within this space.

Balkan London Collective developed in a very grassroots way. We wanted it to be a “by the people, for the people” approach. We connected with a really cool bar in Dalston, which is known for hipster vibes, a very alternative scene.

Qendresa, a London-based Kosovar-Albanian artist, performed at Balkan London Collective’s International Women’s Day event. Photo: Kairo Urovi

Albanian parties in the West tend to be very traditional and cultural and have these systems of oppression that we’re used to. It becomes really difficult to access your culture. When I was younger, in my late teens or early 20s, I often searched for spaces for cultural engagement that would accept aspects of my identity. They simply didn’t exist. And so there was a real necessity to make sure that we were creating and curating spaces for all Balkan people within this space. But also being very firm in our beliefs of being anti-ethnonationalist and very progressive.

It’s been going very strong. We did our second Balkan Pride. We had a singer. We had drag queens. We had different DJs and the vibes were absolutely immaculate. What’s really incredible, as well, is that it’s almost like our entire family has become a part of the process. My mum would do the catering. She’ll make mantia and flija and bring it to the event. People are just so grateful that spaces like this exist, which is why me and Tamara continue to do this. There’s such a demand and necessity to see Balkan spaces like this, because something like this really never existed, especially not in the U.K..

Oftentimes, “Balkan” is solely associated with ex-Yugo countries. We were able to join our collective groups — it’s so incredible seeing Serbians dancing to Valle Kosovare and us dancing to Turkish or Greek music.

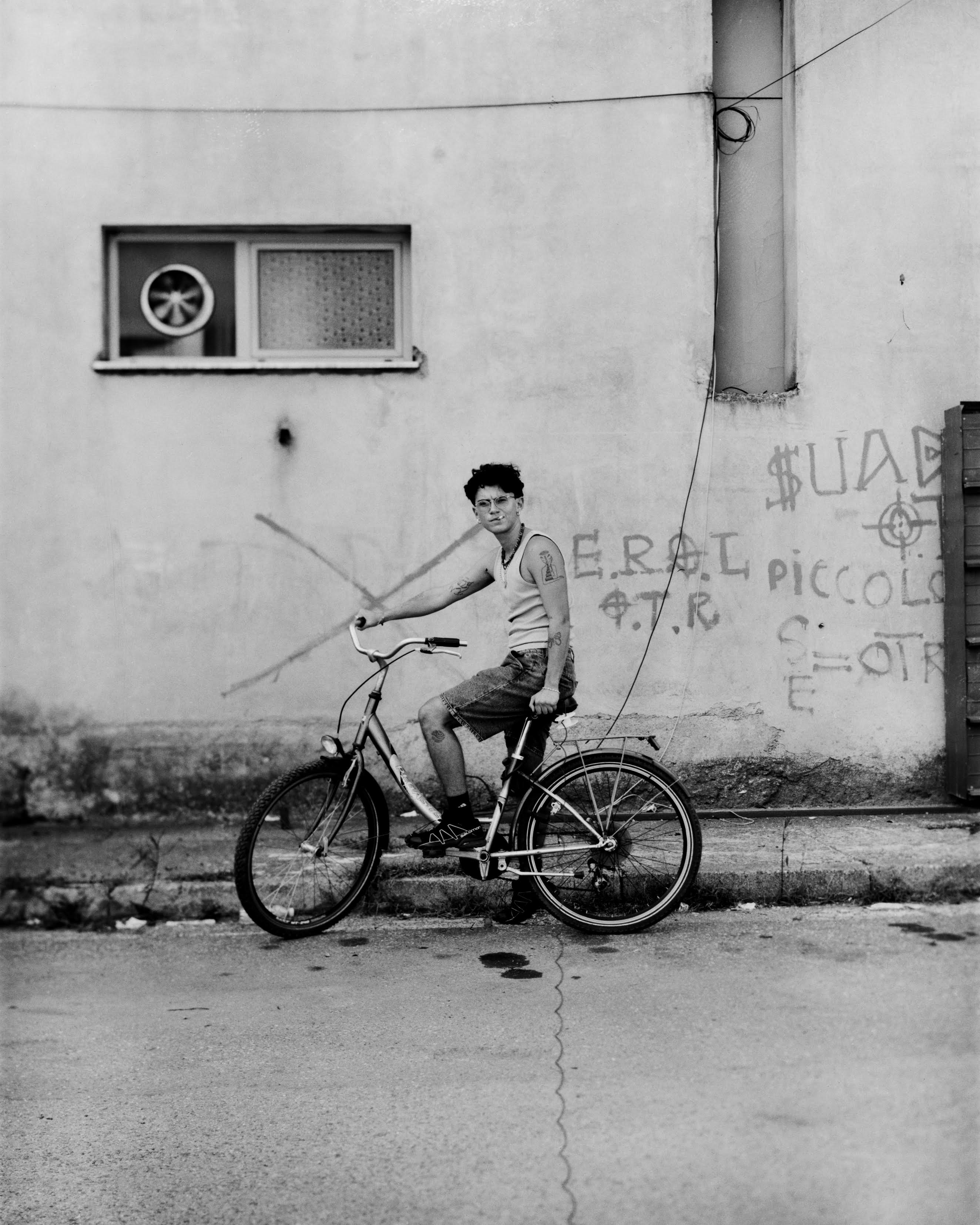

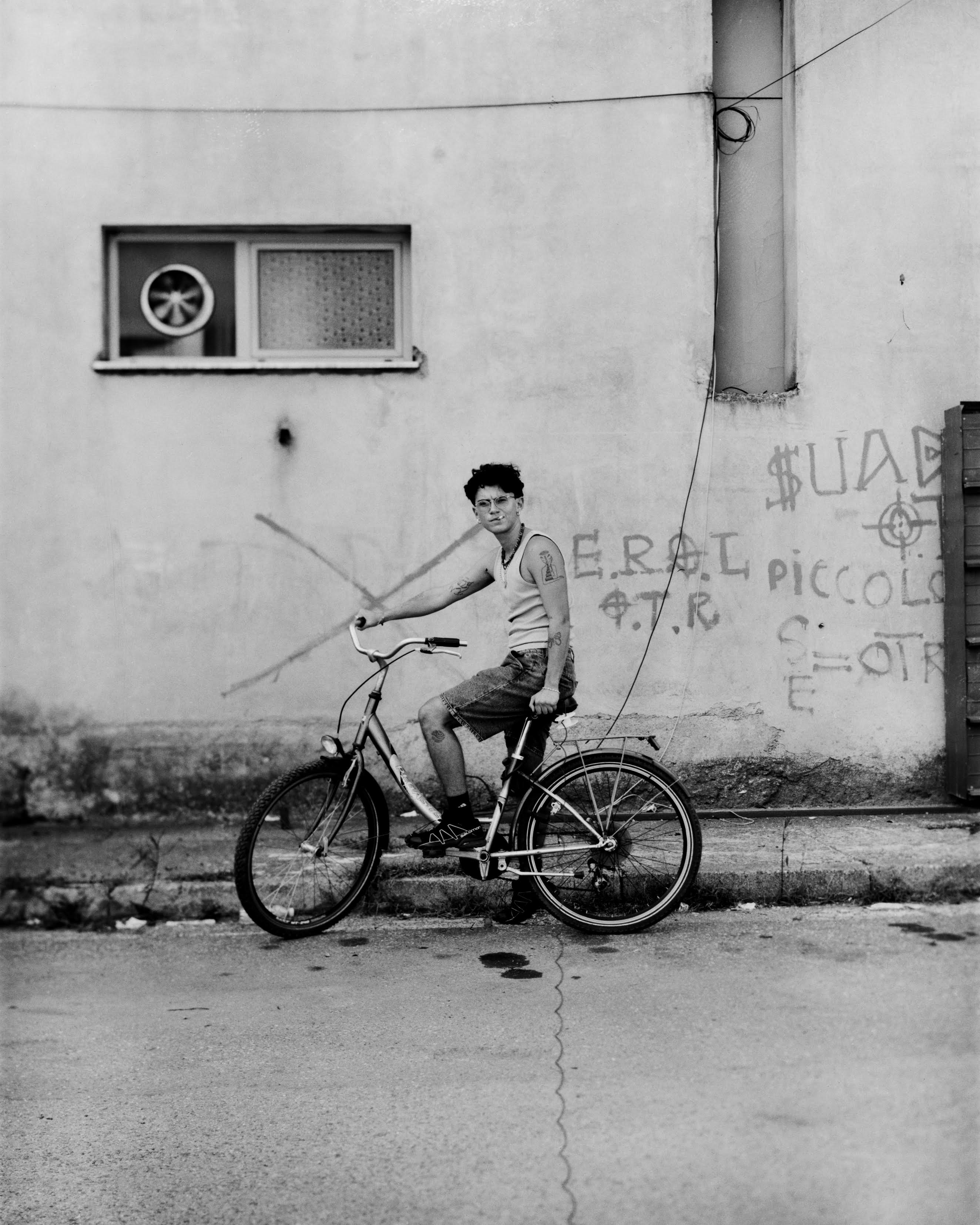

Balkanism aims to embrace and showcase the complexity of Balkan identities. Photo: Arber Sefa

Can you share a memorable moment or piece of feedback from the community, in either Balkanism or Balkan London Collective, that has left a lasting impression on you?

We had a young non-binary person who was coming to these events, quite consistently. At our last event, they came up to me in the smoking section and said “Arbër, you don’t understand how much this means to me. You don’t understand what you’ve done for me, for years, I haven’t been able to relate to my cultural identity, but you’ve been able to infuse that in me.” It was such a beautiful thing to feel, because I always wanted something like this when I was young and never had it. It sounds so cheesy but you can’t be what you can’t see, if that makes sense.

Through Balkanism, I think, one of the most impactful ones was a young woman who’s half Kosovar and half Palestinian. When we started posting about Palestine, she sent us a very long message saying “you’ve literally infused both of my cultural identities in this space and it just feels so impactful to see Balkan people also be really supportive of Palestine.” Those sentimental moments of people just showing their gratitude are the best thing ever. We’ve even had a Balkanism wedding. Two people met through the page and ended up getting married two years later.

Feature Image: Iva Mareva.

This article has been edited for length and clarity. The conversation was conducted in English.

Editor’s note, January 10, 2025: The original version of this piece stated that Tamara Vujinović was a co-founder of Balkanism. It has been updated to reflect the fact that she is the co-founder of Balkan London Collective rather than Balkanism.

Want to support our journalism? Become a member of HIVE or consider making a donation. Learn more here.

Want to support our journalism? Become a member of HIVE or consider making a donation. Learn more here.