KOSOVO2.0

Patients are in the hands of a system that does not recognize them

A decade of failure to make HIS functional leaves patients carrying their own physical files.

In-depth

More

Patients are in the hands of a system that does not recognize them

A decade of failure to make HIS functional leaves patients carrying their own physical files.

Longform

More

Voting from afar

The vote of the diaspora expresses a desire for involvement that extends beyond electoral participation.

Perspectives

More

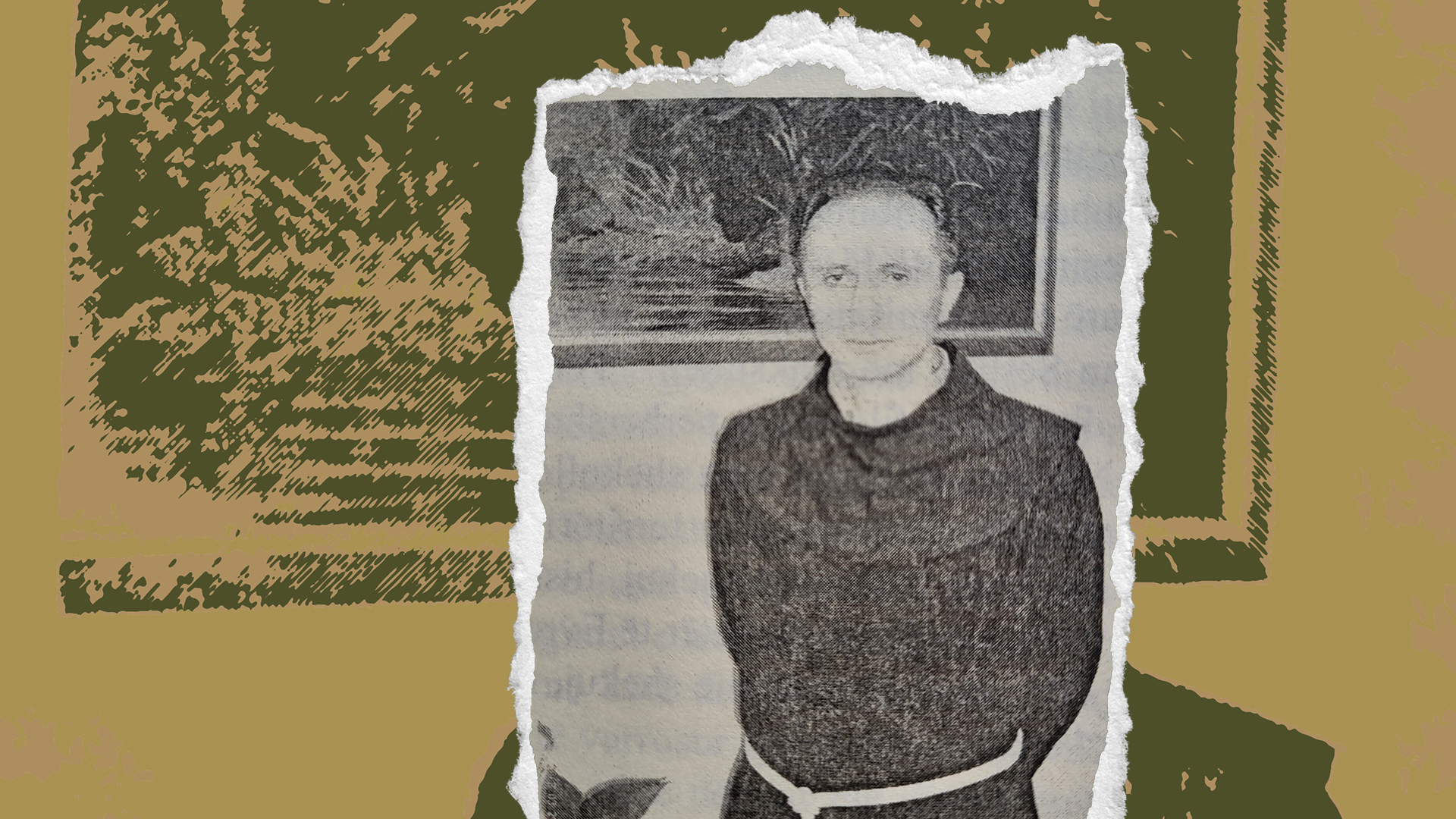

Ermela Teli’s documentary as a cathartic process of memory

“A film about the contradictory relationship between human beings and ideology.”

Videos

More

Recommended

The silences and noises of a decade

Become a member of HIVE or consider making a donation.

Photostories

Explore more

Become a member, support our journalism.

At Kosovo 2.0, we strive to be a pillar of independent, high-quality journalism, in an era where it is increasingly challenging to uphold these standards and pursue truth and accountability without fear.

To ensure our continued independence, we are introducing HIVE, our new membership model, which offers those who value our journalism the opportunity to contribute and become part of our mission.