How does one publicly make use of one’s mind to begin the conversation about the first Pride march of Bosnia and Herzegovina (on September 8), and how can one discuss this issue?

It seems to me that, seven or eight years after the war, when I used to play “Celluloid Closet” in the classroom, an HBO documentary providing a historical overview of LGBTQI representation in Hollywood, it was easier to start a conversation about such topics with students at the Banja Luka University English Language Department than it is today with a new generation of young feminists and queer theorists in the Balkans coming of age.

Ten years later, when the movie “Brokeback Mountain” came out, most of them reasoned — although not without backlash, and a few hateful looks — that even in these crags of ours, there has to be some truck driver who likes “boys,” who isn’t allowed by the patriarchal macho culture to come out. The general consensus was that girls had it easier, but more or less they came to an understanding that being an LGBTQI person in our society is a predicament.

It was important for my students to be able to publicly articulate themselves, talk and write about lesbian, homosexual and queer sexuality, while personal opinions were kept “at home” and discussed in coffee shops.

To pass their exam they had to be familiar with gender and sex, “compulsory” heterosexuality, gender as a cultural configuration, performativity, media representation, the sign and the signifier, the symbolic order, and a few other concepts. It was irrelevant what the personal beliefs of people were, but all these subtopics were used to spread their horizons, making the acceptance of others and of different people more digestible and less problematic — it seemed to me that theory was never as efficient in shaping practice as it had been back then.

Academia had offered only bits and pieces, and all around there was a world of those who kept on either living incognito, or in tacit agreement with postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina.

From my experience as a professor in Banja Luka, Sarajevo and Tuzla, I would say that only a small portion of the academic community teaching about gender and queer studies was intent on introducing LGBTQI topics as an obligatory part of the curriculum. However, neither Jeanette Winterson, Judith Butler, nor even the Brontë sisters according to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, could have been read or interpretated without the queer key.

Flaunting intentions and individual kamikazes

Dormant lay such knowledge torn between fragile and flaunting intentions of an occasional academic kamikaze and tough institutions, resulting at times in vehement discussions, profound analyses, an occasional student’s ‘coming-out’ and the best and brightest of them leaving the country for good.

Even some seemingly white and straight women would often think of themselves as queer due to their politics, and students knew how to read this. This particularly rang true when the issues of sexuality and politics overlapped, when we discussed public and private lives, and when we all realized that social norms were to “enter the bedroom,” which was jointly hated and resisted by most in academic circles.

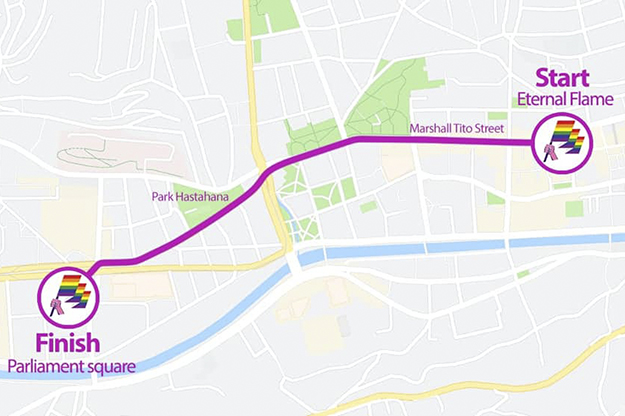

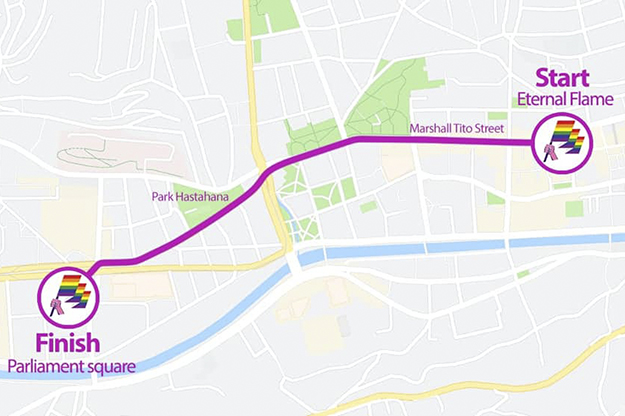

Pride will take place on September 8, 2019. Photo: courtesy of the Organising Committee of the first BiH Pride March.

Living a queer life was possible for anybody who would uncompromisingly oppose “gender, the state, and capital,” as can be read in the book titled “Irreconcilable,” published in 2018. However, in a parallel fashion, there was an entire world of LGBTQI people living under the radar, with no access to academia and jobs, often faced with prostitution and various forms of slavery and oppression, with no opportunities to come, talk, meet, and make friends.

Academia had offered only bits and pieces, and all around there was a world of those who kept on either living incognito, or in tacit agreement with postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina.

On the other hand, and in particular following the dissolution of the ambitious gender studies master’s program in Sarajevo, which appeared to be a solid start to more serious conversations, gender and queer topics were somehow taken over by the non-governmental sector. The last generation of students was enrolled in 2010-11, after which the program was shut down.

At first, there were sporadic attempts to organize queer parties in Banja Luka, with a lot of security and occasional problems. After that, things became a bit more systematized: lectures were held at the feminist school of Žarana Papić, organized by the Sarajevo Open Center as a two-semester academic and activist educational program, a 2015 psychoanalytic seminar was held in Tuzla organized by the Workers’ University and the feminist festival named BLASFEM is being held for the third year in a row, organized by the Banja Luka Social Center (BASOC).

Thanks to their community work, the Q Association, Sarajevo-based CRVENA (Red), Prijedor-based Youth Center KVART, the Banja Luka Citizens’ Association Oštra Nula, Geto and others constituted the main pillars of support for the tiny bits of activism that showed themselves, seeking to branch out.

The fact is that we all, no matter our social class, were and still are afraid of the violence in BiH that has somehow always been at one’s fingertips.

However, it all seemed insufficient. Once, I happened to attend the most amazing underground LGBTQI party in Prijedor, a city that struggles with its war past to this very day, and met feminist activist Boba Dekić who told me the following: “Danijela, our generation has completely failed, this will be achieved by the young people.”

My work colleagues throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina and the wider region didn’t want to out themselves, and neither did any politicians — the ultimate celebrities in our region — who did not even want to go to an underground LGBTQI party. A parallel life on online dating platforms such as Romeo, Tinder, as well as abroad, was in motion without too much noise, and it seemed as if it would continue this way.

Even after Serbian Prime Minister Ana Brnabić entered Serbian politics as a publicly self-identified lesbian — whom the communists and feminists saw through as the introducer of austerity measures — nothing similar has happened in BiH.

The March will lead down ulica Maršala Tita (Marshal Tito street), the main boulevard in Sarajevo. Photo: courtesy of the Organising Committee of the first BiH Pride March.

The fact is that we all, no matter our social class and even association with political elites, were and still are afraid of the violence in BiH that has somehow always been at one’s fingertips.

We had the first Queer Festival in BiH in 2008 and the International Queer Film Festival Merlinka in 2014 as reminders of that violence and of the sharp opposition from the religious communities of this country. Even today, I am banging my head with the question of whether the police will want and be able to protect my fellow comrades in Sarajevo on September 8 this year.

Entering politics

With the announcement of the first Bosnian and Herzegovinian Pride under the motto “We’re coming out,” things became further entangled.

The postwar enthusiasm was replaced by impoverished everyday lives, by the widening gap between the rich and the poor, conservatives and progressives, women and men, religious and secular people, while the professionalized LGBTQI sector not only stopped caring about the gay truck driver from the beginning of this story, but became segregated within itself based on social class and interests, justifying it through personal political choices.

Some entrenched statistics say that the segment of LGBTQI people always represents between 10 and 15 percent of the population in a society. Specifically in BiH, there is no available research in this field. In socialist times, homosexuality was punished, and then accepted under the “don’t ask, don’t tell” doctrine, as discussed in the research of historian Franko Dota — it seemed that by the means of “NGO-centring” grew an elite circle of well-to-do youth who expect a salary in return for their activism.

I view Pride as a part of a solidarity network of these and other struggles.

One friend, a seasoned gay activist, recently told me that he is actually wondering who he is going to be marching for on September 8. Because, it is questionable whether the LGBTQI crew would stand side by side with ethnically cleansed Bosniaks, Serbs or Croats. Or with David Dragičević or Muriz Memić, the youngsters who were killed while their assassins were never caught; if they will stand with the disenfranchised workers of DITA, with the Women of Kruščica who are defending their river, and whether they would oppose the installment of human cages and stand in solidarity with the people on the move who want to cross BiH to reach the European Union.

I view Pride as a part of a solidarity network of these and other struggles, and I believe that we must not turn a blind eye to the number of other issues present in the fragile left spectrum of BiH.

It remains to be seen how to do this and through what kind of continuity. The first Pride needs to be maintained, and there should be no discussion about it.

Great expectations, little solidarity — Will we come out?

When I was a 20-year-old — at the turn of a century — I was discovering feminism and the LGBTQI and queer movement, which seemed for me to be one uniform struggle, one front against collective deceptions, against silence when faced with injustice, against the cruelty of everyday life. A clear and unequivocal criticism of the agreement of the patriarchy on gender and sexuality, of war and violence as oppressive management techniques, with insights about the liminality of specific positions on gender, the system, and the state.

“Our Struggle” is one of the slogans of the Pride March. Photo: courtesy of the Organising Committee of the first BiH Pride March

This is why knowledge is important, in order to discover what types of nightmare leads people to engage in prostitution, how women and male rape victims deal with their trauma, in order to think about surrogacy as a highly complex political issue, not only with regards to what its arrangement legalizes, but also in terms of what happens with a “rented” uterus and what happens to women who see this as the only way to have children and who can actually afford this.

This year, the aforementioned Ana Brnabić became a mother in Serbia, where neither gay marriage, artifical insemination of same-sex partners nor surrogacy are allowed; this is possible only for those benefiting from middle-class privilege and because of the fact that they are members of the political elite.

Have we become wolves of the left living in the decaying peripheral states of southeast Europe?

If all relations are connected to either power or powerlessness, doesn’t this make it challenging to build solidarity?

Today’s debates push me to ask myself whether there is a place in LGBTQI activism for feminists and communists today. Why don’t some feminists recognize trans people and why are some trans people blind to feminist struggles, discarding them as not relevant to their person? What types of crises are these? Where and how is power distributed within leftist circles?

Have capitalism and the logic of privatization eliminated not only our memory of ownership under socialism (which may not have been perfect, but in comparison to what we have today, it constitutes a civilizational step forward), but also abolished the possibility to think differently?

Have we become wolves of the left living in the decaying peripheral states of southeast Europe?

It is up to us to decide which policies will be advocated for and how, who will represent “our policies,” what kinds of solidarity networks will be knit and how. Will we keep on using old solidarities and building new ones — maybe even where there weren’t any before. Because, well, it’s tough to do it.

Otherwise, we can all “come out” — not only to Pride, but also “get out” of our countries of residence. Many have already done so.

Feature: courtesy of the Organising Committee of the first BiH Pride March.