There are people who devote their whole life and career to one cause. Hamze Bytyçi is such a figure. Born in 1982 in Prizren, Bytyçi now lives in Berlin and devotes his time to activism, cultural and social work as well as directing and acting. The productions he shapes and takes part in cause waves in Berlin’s cultural landscape and reach far beyond the city, occasionally also to Kosovo.

His activist spirit arose early, out of necessity and quite naturally. Due to the increasing political tensions and Milošević’s oppression of Kosovars, his family migrated to Germany in 1989. At first they had many temporary stays in residences for asylum-seekers, again being exposed to exclusion, again being denied basic human rights.

Bytyçi was only 8 years old, when he fought the deportation of his own family and joined an activist church asylum association in Tübigen, Germany. What came after this first protest against the authorities’ decision was a succession of other activist engagements while the forms of expression changed from acting and theater, to film and art.

No matter what Bytyçi does, his aim is to counterbalance the obstacles that the Roma community faces due to marginalization, racism against Roma, Ashkali and Sinti and socio-economic disadvantage. Although it is due to a nationalized, majority culture that causes marginalization, Bytyçi is convinced that only culture has the potential to change how we perceive the cultures of others and also what is supposed to be our own.

In 2015, he founded Roma Trial e.V., a transcultural Roma organization and interactive platform with the goal to bring the complex problems of antiziganism (anti-Roma discrimination) onto stage and screen — but especially to change mentality.

Bytyçi also began Balkan Onions, a film school for Roma based in Prizren every summer, as is possible. Bytyçi says he bases his work, “on improving human rights in regard to real life economic and social marginalization, mostly of the most vulnerable groups. Specifically with the biggest minority in Europe, the 12 to 15 million population of Roma, whose history and present of oppression is continuously sidelined and eradicated.”

Some of that history includes the Holocaust, during World War II, where more than a half a million Roma and Sinti were killed, a quarter of their population at that time.

K2.0 sat down to talk to Bytyçi about his social and political commitment and engagement with the issue of Roma marginalization, and about the potential of art to challenge negative stereotypes.

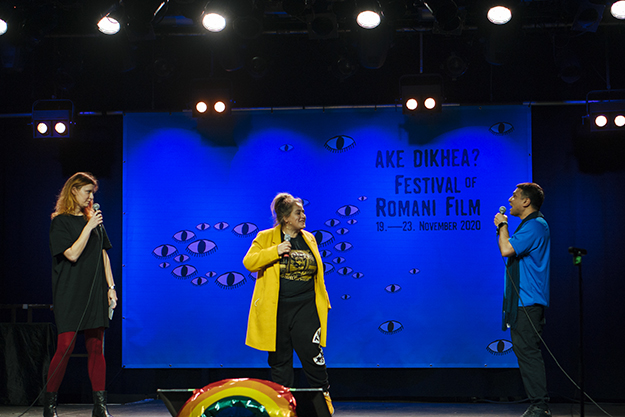

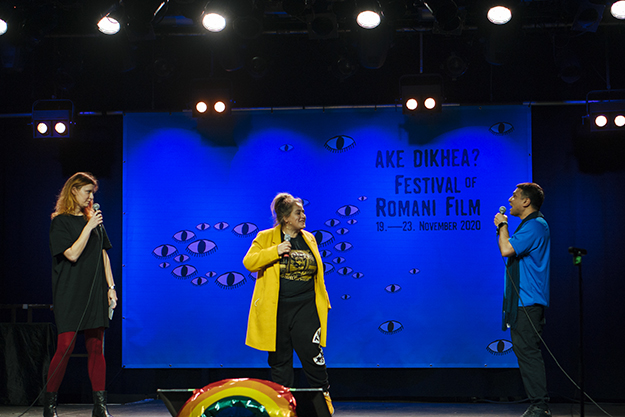

The “Ake Dikhea” festival is one of the events that Bytyqi’s Roma Trail e.V. organization produces. Photo: Stephanie Bellantine.

You have many different roles, as an actor, director, project manager. Can you elaborate on your roles and recent projects?

I do a lot of community work, I work as an educator in theater and media visiting schools across Berlin. But what I spend most time with is listening. I closely follow the behavior of the artistic field and create space for subject matter and people that go otherwise unheard. This is something I had to learn as a producer of festivals and biennials; to listen, to hear and then, of course, to act. I believe in the power of art to challenge how we view ourselves and others. But my job is not to create art, the art is done by the artists themselves. I am just the cultural midwife that creates space for them and encourages them to bring it alive.

In 2015 you founded the organization Roma Trail e.V. Can you tell us about the organization and how it operates?

When we founded the organization in 2015, we wanted to create an interactive platform that is self-organized by those coming from the Roma and non-Roma community to create transcultural meanings and fight antiziganism through creative exchange. Ever since then it works around three focal points: Arts & culture, youth & education, knowledge and politics. Our focus is on film and art festivals, cultural and political education work for young people and adults, creative theater and film projects, summer schools and seminars against antiziganism. So it works as an umbrella organization for various activities.

Can you give us some examples of what it has been doing recently?

I am the co-director and curator of the transnational Roma-Filmfestival “Ake Dikhea,” which translates from the Romani language as “Do you see (?). The longer title is: “Do you see it is possible to self-organize a film festival without a big budget and great network?

It is the fourth time this year that we are presenting films from or dealing with matters concerning Roma communities.

This year we had to relocate the program online, with our partners SO36 [ a famous alternative arts venue in Berlin] still offering the venue for live-discussion rounds and an online platform. The outcome of the pandemic, moving the festival online showed the potential of images to connect dots, historical connections, common causes and pains, across the globe. We were fascinated by the positive feedback from Roma communities settled in New Zealand to Latin America.

Hamze Bytyçi has been an activist since he was 8 years old. Photo: Nihad Nino Pusjia.

What is the criteria you use to curate your film festival program? And why is it so different from others?

How we curate the festival and which films we chose changed throughout the years based on the reactions. I had to dive deep to find films made by Roma and learn to be cautious about those made on and about Roma from those directors outside the community. Seeing so many films on this topic, we developed a visceral understanding for who really is in solidarity and empathizes and who just would like to become famous by telling stories of others.

How do you tell cinematically if a film is merely appropriating the theme or how are well-worn stereotypes reproduced cinematically?

You can see in the first few minutes of the film if a director got it, if he got the discrimination right or if he has in some way been part of the community fighting against racism. Sometimes the line is thin. Many produce films with good intentions but the films are cinematically contaminated with well-worn stereotypes. As a rule, we exclude each film that begins with a shot of garbage or barefoot naked poor Roma. We do not screen this, even if well-meaning or produced expensively. It is counterproductive in fighting stereotypes and racism against Roma, Ashkali and Sinti. It is simply not enough.

So you prefer choosing films made by those from the Roma community?

No, let me say this differently. If well made and meant, of course we welcome films from non-community directors, we would be stupid and just like our excluders if we would not. But it has to serve the political aim. At the same time it needs to act as a counterweight to the white man directors of which there are so many in this world. We do pay extra attention to intersectionality and therefore encourage Roma directors, producers and actors to hand in their films. A few years ago, the number of “Roma directors” was limited but is now increasing. And I am so happy about that because it leaves a remarkable impression that encourages others who self-censor their history or are socioeconomically marginalized.

Another point of the festival is to encourage participation and creative activity from the margins?

Yes, for sure. Now with technological development, everyone can do films. It does not need much to make your story and tell it to others. And if the story is good, the film is good. Everybody can do it. There are so many stories related to the life and history of the Roma community that are never told and I hope more will consider telling these stories through images.

While I do not produce my own films, we as a jury offer the space and try to create a program that is aesthetically pleasing while having a narrative structure that is somewhat challenging, original and not a mere reproduction of other films about Roma.

Hamze sees his role as being a cultural midwife that creates space. Photo: Nihad Nino Pusjia.

Do you also have films that come from the Balkan region and Kosovo specifically?

Yes, of course. This past year, we had an amazing film by two guys from the Roma community in Prizren. They made a film about the special Romani flag of Prizren called “Bajraku”; it was cheaply produced but it won prizes. At that moment they were ambassadors of their own reality, with images speaking so much in the present. They enjoyed moments of glory on stage at the Berlin Film festival.

I was happy to hear that this gave them the motivation to continue making films. The two youngsters had participated in the film summer school we organize called the “Balkan Onions.” It took place for the first time in Prizren in 2015 and has since then been produced almost annually. We invite those from the Roma community internationally to participate, to learn how to make a film and think about moving images. And it made me proud to see that the educational work comes to fruition.

I think making art is the only way for reconciliation and to work against discrimination.

What was your motivation to implement your educational approach in Kosovo?

It was interesting to me — on the one hand — due to the possibility to go back to my roots. So I became a director of the film school in order to influence society back home. And once I started, I realized that what we did was unique not only to us but also to the people in Kosovo and those involved in cultural projects, because no one had done this before.

When we started the film school, DokuFest was running parallel and we became friends with the organizers and formed alliances for upcoming collaborations. It proved a good idea to locate the workshop in Prizren as we connected with the local community and were able to build bridges. And even though the organizers of DokuFest belong to the majority ethnic group in Kosovo, they were very sensitive to us.

As a child your wish is to be part of a group and if you are excluded it makes something within you. It is a trauma.

Do you plan to do more film schools and workshops in order for art to foster building bridges between the Roma minority and others?

I think making art is the only way for reconciliation and to work against discrimination. Feeling through art is less politicized and it can be an immersive power to transcend the boundaries. I witnessed this in the past with Balkan Onions through public interventions where there is a direct dialogue through culture and art with people.

We staged a spontaneous performance in public space, a dance with Michael Jackson music, and a banner against discrimination. I expected some negative comments, but we only got positive reactions. I like to facilitate and motivate people to not shy away from each other. There are many critical bright-minded cultural initiatives in Kosovo that are worth collaborating with in the future. I believe that these can improve the life of Roma communities in Kosovo very much.

The Balkan Onions film school takes place in parallel with DokuFest and reaches out to Roma across the world. Photo courtesy of Hamze Bytyçi.

Still the reality of socioeconomic marginalization and lack of infrastructure and education support for Roma prevails in Western Europe and in the Balkans, including very visibly in Kosovo. How do you think art and film can raise awareness of these issues and even change it? What is their power that words alone cannot do?

I would say different from words, art gives the possibility of dialogue. What humans have always done since the Greek playwrights is to create space for people to be in a dialogue. To speak, to talk about things is a part of the holy process, so that means that theater, film and whatever you are doing is communicating beyond words.

How is this linked to your experiences of exclusion? Why is it crucial that Roma are given the space and place and outreach to speak themselves about marginalization?

As a child your wish is to be part of a group and if you are excluded it makes something within you. It is a trauma. You always wonder why this happened to you, and why are you different? I spent years wondering what the difference between me and the others is. This is a sickness that grows in you. And here I come to the point of diaspora double exclusion that is also linked to self-denial.

My father used to tell me, tell the others you are Albanian, Turkish or Italian but don’t say you are Roma because your friends will not play with you, because they are afraid or whatever. And this is something I will never forget. So I tried to deal with it in my way, which was not always the best one because I was in a chaotic fury without being able to speak proper German.

So speaking up in broken German without being part of the system and belonging to its community was tough. But then in school I got the support from the theater class, where I realized I could be anything I wanted to when I performed other roles. It was the only way I got applauded and appreciated for who I already was and with the potential that I had within me as a human being.

And now with your work you try to make the life of those experiencing similar things easier? To find a healthy way to channel and mobilize?

Exactly. Part of it is to leave the comfort zone, but the comfort zone assigned by others to a minority is not always the best to stay in. So art, acting, producing images can liberate. Personally, without the anger that I felt due to continuous exclusion, I do not know if I would do what I am doing today, combining activism and arts. I did not choose deliberately to work in this way in this field.

I did not choose to leave Kosovo — or better — to be expelled. And when in Germany we spent years in asylum-seekers residences, having to move frequently, being excluded and protesting against it. That was something that influenced me from an early age. It came naturally to me, arts came with it as well, because it empowered me.

So my engagement with theater is not only looking straight, but to see what comes to you along the path and then give it a space.

Now from this experience you facilitate others’ access to acting and theater, but you also still act yourself. Can you tell us about the plays you were involved in?

I completed acting school in 2005 in Freiburg while I was already active in the first Roma- theater in Papillon in Cologne. Later, collaborations with Maxim Gorki Theater in Berlin happened. I had the opportunity to direct my first play “Romeo rennt” in 2012. I got the inspiration for this play from my social work with a Roma youngster about 15 years old who had issues with the police, parents and all forms of authority.

One day this young man was riding a motorbike without a helmet, without license, with another friend at high speed until the police stopped him, by blocking off the road. A chase and run began until both fell and the youngster threw a pile of dogshit on the face of the policeman. Funnily enough this was not a joke but real; and he was condemned to do social work as penalty. I then suggested to the state authorities to make him pay by participating in theater workshops.

So I combined sectors, and from my own experience with my educational and artistic tools, I recreated this story in a play with other actors and staged it at the Ballhaus Naunynstraße in Berlin.

Is this the cultural midwife role you were speaking about?

Yes, so my engagement with theater is not only looking straight but to see what comes to you along the path and then give it a space. Here it was the stage, either as director or as an actor.

What can theaters do that other art forms cannot do considering the representation, other life-forms of Roma community?

The “Roma Armee” (Roma Army) play that premiered at Gorki Theater under the direction of Yael Ronen is one example of the best antiziganism workshops. Theater plays are immediate connections to people, they travel from town to town and this one had a huge tour through different cities in Europe. The audience and actors are live, they cried, laughed and fell in love and you get so many reactions after the show, conversations which make up for the richness of theater.

The play played with the utopia of a Roma Army attacking Europe to make it democratic hinting at their century-long marginalization. And oddly, people from the audience did not know what is true or false, but they understood the realness in the utopia, the gravity of the past and present in relation to the eradication of Roma and Sinti in Germany and Europe in general.

A lot of people criticize the quest for participation as identity politics or token art. But it is way more than that, it is about filling these spaces of dialogue with diverse experiences of marginalization.

Cultural productions be it theater, film or art still operate within a system that is imbued with homogenizing understandings of culture, identity and nationalism. What are obstacles and criticism toward your approach?

There is criticism from the Roma community and the bigger national communities. Some Romani activists do not want to participate in Q&A with Ceks (non-Roma) because their pain is too deep and their frustration too high. But I try to build bridges and encourage a critical dialogue between people belonging to some national or community identity. To trace their stories in their trajectories of what has happened and continues to happen to the Roma minority, while trying to remain intersectional.

Another important aspect is the self-denial of many from the Roma community. Denying their heritage, be it Ashkali, Egyptian or Sinti, trying to subsume yourself under stronger nationalities or remaining silent about it which also erases the genocides that happened in the past from the record of history.

So to summarize you believe in the empowering aspect of doing art and influencing culture toward a less discriminatory spirit. When you label your events as Roma film festivals do you then speak to one Romani culture and do you think such a thing exists?

With naming it Romani art and culture, I try to create the space that is otherwise not given to them. My intention is to shape awareness and deconstruct notions of identity attached to them as part of the Romani community. Only in this way can there be defense, a dealing with the past and creation for justice. I oppose the use of speaking about one single Roma culture, there is no one Roma culture, there is a variety. Just as culture is not a static homogenous entity, identity too is fluid, it can invent and reinvent itself. But we must be aware of the history that has shaped us in order to improve the future.

Do you think labels such as “Roma art” can bring change or are they counterproductive reinforcing exclusion? And how do you deal with it?

A lot of people criticize the quest for participation as identity politics or token art. But it is way more than that, it is about filling these spaces of dialogue with diverse experiences of marginalization. You do not have to be visible as a person of color to be marginalized, white people can be marginalized too. For me if you are an artist and you come to a show as an artist, then you are this in the first place. But to make space for those marginalized, for the sake and process of facilitating, I do call it Romani festival for instance. Otherwise it is difficult to do that.

Could an intersectional approach inhibit a homogenization of one Roma culture?

Yes of course! And this is what we try to do all the time. We need brave people from the LGBTIQ+ community more than ever, not to fill expectations or a quota but to make visible through activism and art that identity is constructed and that you chose your identity, not others. They know what it means to belong to nothing. They know the pain, they experienced pain. And exposing this pain is so crucial for bringing us forward.

It is an honor for me to do what I do but I am also restless.

Do you encounter difficulties in positioning yourself within the cultural politics that try to understand your activism, while at the same time risking marginalization by labeling it?

We are still in the matrix and power dynamics of fighting for space of representation, of creating our own image and diversifying homogenization. I think it will take some generations where we can stop debating about labels, and I hope one day the Romani artist can be just the artist without the need of an appendix. For now, we create our space in the paradigm of culture, we break it, question it, and hopefully one day we can be the artists without reference to our ‘backgrounds’ while being appreciated for the art we bring to the world.

What needs to change in the cultural politics in Germany and abroad to facilitate more active participation of Roma communities in art and society?

I always say, we are glad we are accepted to play in the Paralympics. But very often the artistic value of artists, filmmakers and directors falls into oblivion. There is more to it than it being told or created from a Roma, it has an artistic power, a life and higher spirit. Artists such as Damian Le Bas [a famous British Romani artist] are Champions League, but we are kept in the Paralympics. We are at the beginning of fighting for inclusivity and it is still a long path.

What keeps you going is the motivation to make space for the stories of “others” coming from the Roma community across the globe, but it is also anger, when do you think your hunger for justice will be stilled?

The childhood house of a person is its treasure. My treasure was taken away, without any apology by Serbian authorities, without compensation. Following that: Exclusion and racism in Germany. It is an honor for me to do what I do but I am also restless. I cannot stop. As long as this restlessness will not stop I will continue to do what I do.K

Feature image: Lutz Knospe.