“I feel endangered and I fear for my life,” wrote Šejla Bakija in a report filed to the Police Department of the Podgorica Security Center on August 26, 2021. Just over a month later, on September 30, Bakija’s 28-year-old former partner Ilir Đokaj murdered her in the yard outside her family home in Tuzi, firing 11 bullets and severely wounding her father as well.

Three months after she left Đokaj, whom she listed in her report as her fiancé (the media and police would later describe him as her “common-law husband”), 19-year-old Bakija moved back to her family home to live with her parents and younger siblings. Đokaj started to harass the family afterwards, making threats and coming to their residence demanding that Bakija should get back with him. She reported everything to the police; after her death, her report found its way to the public through social media, its authenticity confirmed by the police.

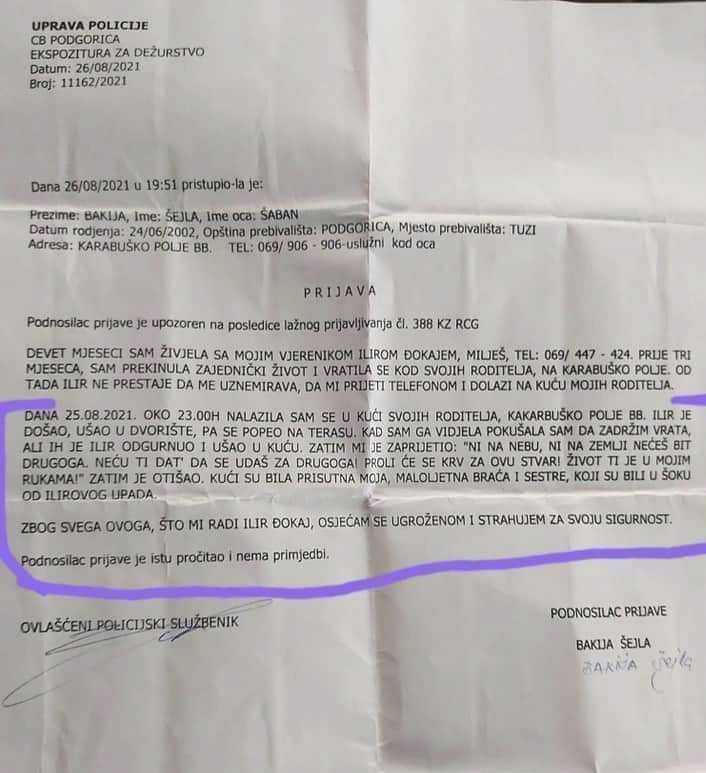

The statement Šejla Bakija gave to the police on August 26 found its way to the public after she was brutally killed. Photo: Jelena Kontić

“On August 25, 2021, around 11 pm, I was at my parents’ house… Ilir came, entered the yard, and headed to the terrace. When I saw him, I tried to hold the door shut, but he pushed it open and walked into the house. He threatened me: ‘Neither in heaven nor on earth will you belong to another man, I won’t let you marry someone else. Blood will be shed for this. Your life is in my hands!” Then he left. My underage siblings were at home, so his intrusion left them in shock. Due to everything that Ilir Đokaj has been doing to me, I feel in danger and I am concerned for my safety,” the report from August 26 says in conclusion.

Competences over prevention

The public in Montenegro realized in the days after the murder that the authorities had failed to react, despite the fact that Bakija had described the harassment and threats in detail and voiced concern for her life.

On August 26 the prosecutor from the Basic State Prosecutor’s Office who was on duty at the time assessed that Bakija’s report did not contain “any elements constituting an offense.” The police used this to justify their inaction. The State Prosecutor’s Office said that they acted “correctly” and “in line with the law,” and that they do not have the authority to act preventively. The High State Prosecutor’s Office said the same thing.

“Are there any elements constituting an offense now?” asked the people who took part in the protests held across Montenegro some days after Bakija’s murder.

Yes, there are “elements constituting an offense” now, most definitely. But Šejla is gone.

Was Bakija’s life the price that had to be paid so that the Montenegrin legal system would finally heed the calls of all the other girls and women who are in danger? Worse than issuing ineffective press statements or offering support too late, the Montenegrin state’s official response was to simply deny responsibility.

As is obvious, nothing has changed for years, except that the number of domestic violence victims has been growing. Most of the victims are women. Meanwhile, the case law has shown that the perpetrator usually gets by with a warning like “don’t do it again,” or says himself “I won’t do it again” — that is, until the next time.

No response

Research points to disturbing views held within Montenegrin society. For instance, a 2021 study titled “The Perception of Sexual Violence against Women and Girls” shows that one in five men in Montenegro think that when a woman says “no,” they actually means “yes,” while 18.8% think that for victims of rape, “it’s her fault,” i.e. that the woman “had done something that led to rape.”

It is important to note that Montenegrin legislation does not recognize “violence against women” as a criminal act, but only addresses “gender-based violence” as defined in the Law on Gender Equality. This is contrary to the provisions set out in the Istanbul Convention, which Montenegro signed in 2011 and ratified in 2014.

According to the constitution, the Istanbul Convention (whose full title is the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence), as well as other international acts Montenegro is party to, have primacy over local legislation and are directly applied “when they prescribe actions different from the internal legislation.” The convention provides for preventive measures, so the system — had it wanted to — could have taken such measures in Bakija’s case.

However, there was no response to Bakija’s call for help.

I am only a little bit older than Šejla Bakija. After this case, as well as all the previous cases, I am left wondering what sort of message those who should protect us are sending. Because to me it seems that a death threat made against a woman is not taken as a serious concern in Montenegro, not adequate enough to trigger a response.

Numerous requests have been submitted for the law to be improved, but what has the Montenegrin system done in response? Nothing.

What has the Montenegrin system done since September 30, when Šejla Bakija was murdered? The answer remains the same. Nothing. The murderer even turned himself in and chose to remain silent. Well of course. In a society that has so easily remained silent about injustices, crimes, violations, abuse and corruption, in such a society remaining silent is definitely the best defense.

Bakija did not want to remain silent, she spoke out to the police believing they could protect her from her abuser. She is all the more reason for every one of us to stop being silent.

The system that does not offer protection

Lately, people have been saying, “We’re all Šejla.” There have been protests, demands for justice… But no, not all of us are Šejla. Šejla was a brave girl who decided not to keep quiet when it comes to violence. Šejla started telling her story, but she was silenced and became a victim — a victim of an abuser and a victim of a system that failed to protect her.

Šejla was silenced by a system created by those who turn a deaf ear and a blind eye to violence and red alerts like this one, who do not respond to the threats that can be heard clearly, or to fights in their neighbourhood, to the all-too-frequent bruises, to nervous ticks and to speechlessness…

People in Montenegro will no longer be silent about the increase in unpunished domestic violence cases. Photo. Jelena Kontić

Not all of us are Šejla. But not all of us are the inactive system either. People have been protesting and demanding justice. However, we have to be louder! We ought to dare to tell the story. And it is necessary to support those who dare to do so.

In the last few days, the call for us to speak up has been coming from the Ispričaj priču do kraja campaign (“Tell your story to the very end”), which is under the umbrella of the Women’s Rights Centre. Such a call comes while Šejla’s story is echoing through a system that does not listen.

Even though it seems that anyone who dares to speak is unheard, we ought to do so. We ought to tell our stories to the very end. To help ourselves, or someone we care about. So that we do not grieve for another Šejla.

Justice, law, the system, the society and the state will become better when we better ourselves.

Feature image: Jelena Kontić.