Afrim*, a man in his 50s, wandered from one room of the Emergency Service to another. Sometimes he stopped to talk to a doctor passing by; occasionally, he picked up the phone to try to call someone.

About two hours earlier he had urgently brought in his 83-year-old mother. She had a cough, difficulty breathing and lethargy that made it impossible for her to stand on her feet. The oxygen saturation value — which in healthy people is between 95 and 100 percent — was showing 32 percent on the monitor.

She was suspected to be infected with the SARS-CoV-19 virus that causes COVID-19.

Read facts about the virus and how to keep safe, here.

The Emergency Service is the main gateway for patients needing urgent treatment to enter the University Clinical Center of Kosovo (QKUK). After diagnosis and acute treatment, this clinic refers patients requiring longer-term treatment to other QKUK clinics.

But the rapid increase of COVID-19 cases has led to an increase in the number of patients seeking help at QKUK, making it difficult to transfer patients from the Emergency Service to the clinics now known as “COVID.”

“Doctors are saying that there are no free beds,” Afrim said with concern. “I’m looking to find her a place in the Pulmonology Clinic through an acquaintance.”

“We are often forced to wait for hours until beds in the respective clinics are secured.”

Basri Lenjani, Emergency Service, QKUK

Afrim’s mother would stay in the Emergency Service for most of the day. Some time in the evening, she was admitted to the Pulmonology Clinic.

The director of the Emergency Service at QKUK, Basri Lenjani, says that patients who come to this clinic usually stay between four and six hours. But he adds that it has recently become difficult to secure places for patients in clinics where those with COVID-19 are being treated.

“We are often forced to wait for hours until beds in the respective clinics are secured depending on the nature of the problems,” Lenjani says. “This problem has been present especially in recent times for cases suspected or confirmed with COVID-19, due to limited space.”

According to the acting director of the University Hospital and Clinical Service of Kosovo (SHSKUK), Valbon Krasniqi, there are about 700 beds available in QKUK and regional hospitals for the treatment of patients with COVID-19. Over 600, he says, are currently occupied.

That number continues to rise. By Monday (August 10) the number of beds occupied by patients confirmed or suspected to have COVID-19 stood at 654.

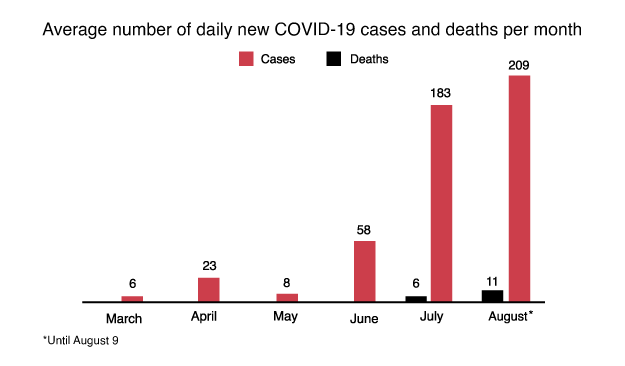

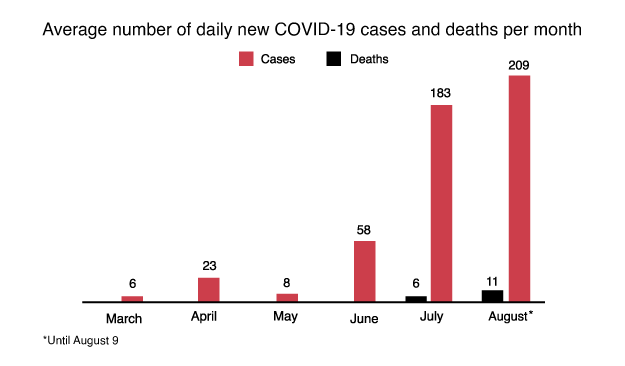

Dramatic increase in COVID-19 cases and deaths

The curve of confirmed COVID-19 cases and related deaths has become dramatic in recent weeks.

The number of new cases announced daily is now regularly in excess of 200, while the daily deaths attributed to the virus is often in double figures.

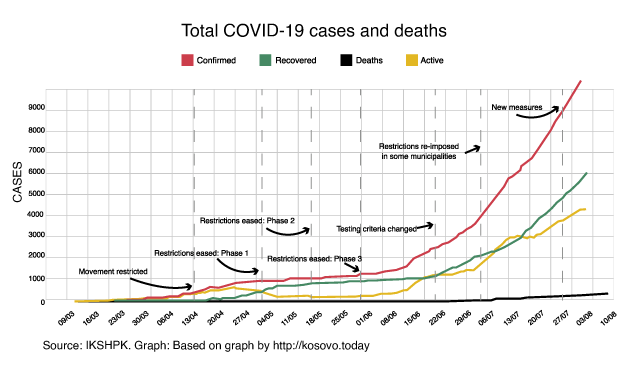

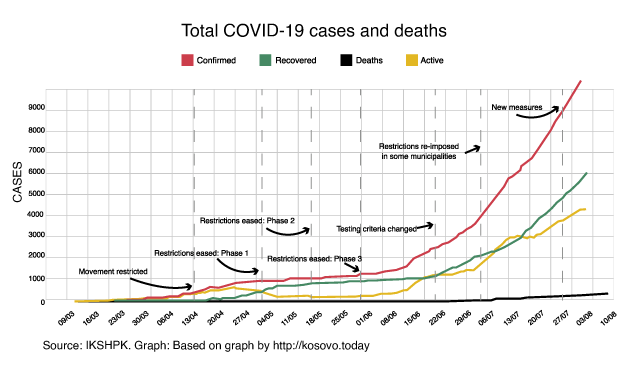

There has been a sharp rise in cases since June, which corresponds both with the easing of restrictive lockdown measures and the change in central government.

The measures taken to combat the COVID-19 pandemic began to be gradually eased in May by the former acting government led by Albin Kurti. Certain business sectors reopened, the movement schedule for citizens was extended, places of worship were reopened and quarantine centers were closed. From June 1, the borders were opened, while government officials continued to call for adherence to safety recommendations, such as physical distancing, wearing a mask and practicing good hygiene.

After the newly formed government led by Avdullah Hoti was sworn in on June 3, restrictions continued to be eased. One of the Hoti administration’s first decisions was to lift the curfew, which had previously been from 21:00 to 05:00. At that time, there were about 1,100 confirmed cases of the coronavirus and 30 related deaths.

Two months later, based on data from the National Institute of Public Health of Kosovo (IKShPK), the official number of positive cases is about 10,500; of this number, over 4,000 cases are active. The actual numbers are thought to be even higher, as the number of tests has not been increased over time, with only a few more than 400 conducted daily.

Meanwhile, at the time of publication, 341 people have died after being infected with this coronavirus.

The reason for this increase, according to the current Minister of Health, Armend Zemaj, is the balance between public health and “economic and mental health.”

“When I took office as Minister of Health, at the time when measures were being eased, I was aware that there would be an increase in COVID-19. I was also aware of the pressure from different sectors for reopening,” Zemaj said in a press conference at the beginning of August.

“It is completely different to manage a pandemic in total closure, and it’s another thing altogether when you have an open economy. But we were determined to maintain public health, but also economic and mental health.”

Meanwhile, hospitals are filling up with patients. SHSKUK acting director Krasniqi says that there is a large influx of patients who come with severe symptoms caused by the disease and who require hospitalization.

“This is putting our system under a lot of pressure to increase the number of beds, and in addition to increasing the number of the beds, that goes along with a large number of health personnel who have to be engaged to treat these patients,” he says.

Krasniqi says that they are working on the creation of a temporary hospital, which would serve only patients with COVID-19. The temporary hospital — which will have approximately 500 beds — is expected to be operational within two months.

Prime Minister Hoti has also said that the government is looking into adapting the Kosovo Security Force (KSF) hospital to treat COVID-19 patients.

Pressure on regional capacity

Currently, patients with COVID-19 are being treated in four QKUK clinics and six regional hospitals. In QKUK, patients are treated in the Infectious Diseases Clinic, the Pulmonology Clinic, Neurology Clinic, Intensive Care Clinic, and in a ward of the Gynecology Clinic that was recently made available.

Patients are also being treated in the regional hospitals of Peja, Prizren, Gjakova, Gjilan, Ferizaj and Vushtrri.

The directors of many of these hospitals contacted by K2.0 say that their main difficulty is a lack of personnel.

The director of the hospital in Vushtrri, Musel Pllana, says that they have a significant shortage of nurses in particular. Another problem he mentions is the relatively old age of many staff, who often have their own health concerns.

Since July, Vushtrri’s hospital has been adapted to exclusively treat COVID-19 patients. Only the Emergency Service is available for other patients, but according to Pllana, this is only for “extreme emergencies,” such as acute coronary problems, which require immediate intervention. Other patients are sent to the hospital of Mitrovica, which is about 15 kilometers away.

“We are in an emergency situation. We have stopped all other services that do not require immediate intervention.”

Muhamet Halitaj, Peja Hospital

Other hospitals have reduced their services for non-COVID-19 health problems.

The director of medical services of Peja Hospital, Muhamet Halitaj, says that patients with COVID-19 were initially treated in two wards of the hospital: the Infectious Diseases and Pulmonology wards. But since these wards filled up, the Psychiatric ward has also been adapted. Due to this, other cases that are not urgent are not being treated.

“We are in an emergency situation,” Halitaj says. “We have stopped all other services that do not require immediate intervention. Because the Covid-19 cases are more severe, we are gradually oriented entirely to these patients.”

It’s a similar situation with the hospital of Prizren. Director Afrim Avdaj told K2.0 that only one of the three buildings of the hospital is currently used for other services. The two other buildings are now designed exclusively for COVID-19 patients.

Adapting clinics for COVID-19

From the outside, the appearance of the Pulmonology Clinic at QKUK in Prishtina looks quite ordinary. Patients and their families enter and leave freely; most of them without any protective equipment other than masks.

But everything changes when you go inside. There is a lot of noise in the corridors. Doctors and nurses run from one room to another. The noise of dozens of oxygen machines makes the conversations between them difficult to understand.

Before turning into a “COVID” clinic, the Pulmonology Clinic had a capacity of about 70 beds. Now, over 100 patients are hospitalized within it.

The rooms on the three floors of this clinic are full of patients. Under normal circumstances, a room in the Pulmonology Clinic accommodates up to three people. Now, in each of these rooms — that are approximately 15 square meters in size — four patients lie virtually adjacent to each other.

Fifty-four-year-old Gani* lies in one of the rooms. He has been in the Pulmonology Clinic for a week, and now says he feels a little better. Gani does not know exactly how he became infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus but says he initially had lethargy, and then difficulty breathing. Three days after the onset of symptoms, he was brought into QKUK by ambulance.

He has only one complaint. He says that staying here has become boring. Since he is lying down, he says he has not left the room, as he cannot even go for a minute without oxygen. “I’ll fall down before I can go over there,” he says, pointing to the door.

“All day it’s like this. Sometimes I lie down, sometimes I sit.”

Gani has no complaints about the medical staff, saying that they are taking very good care of him.

“We work long shifts. Today I started work at 7 a.m. and will finish at 8 p.m."

Nurse, Pulmonology Clinic, QKUK

In the absence of a vaccine and effective medication to treat COVID-19, there is little the medical staff can do for infected patients. The current treatment is focused on symptomatic relief, such as administering pain relievers, medication for coughs and oxygen treatment for those with breathing difficulties.

As Gani shares his impressions about his treatment, a nurse comes into the room with a large bottle of oxygen.

“It’s a pretty tiring job,” the young nurse says, as he pants in exhaustion from pulling the bottle. “We work long shifts. Today I started work at 7 o’clock in the morning and will finish at 8 o’clock in the evening. Tomorrow I’ll work at night; I’ll start at 8 p.m. and then finish at 7 a.m.”

He works in Ward D on the second floor of the Pulmonology Clinic and provides assistance to about 12 patients. He says that the ward where he serves is full of patients, and that it is similar in other wards.

In addition to physical and mental fatigue, he’s also concerned about the risk of infection. He points out that many of his colleagues at the Pulmonology Clinic are already infected.

Protecting healthcare staff is a challenge for all health centers in the country. According to Faik Hoti, the Ministry of Health spokesperson, over 750 health workers have been infected with COVID-19 to date. The bulk of them, about 430, are nurses.

The infection of healthcare workers, according to Hoti, is an additional challenge, which complicates the battle with the coronavirus, the end of which is nowhere in sight.

The long road to a vaccine

There are currently more than 20 million people infected with the Sars-CoV-2 virus worldwide. Over 700,000 have died. The vaccine remains a scintilla of hope to help bring the pandemic under control.

Vaccines typically require years of research and testing before they are approved and mass vaccination programs established. However, given the scale of the current pandemic, scientists are racing to produce a safe and effective vaccine against SARS-CoV-19 within 12 to 18 months.

The steps to a vaccine

There are a total of three phases of clinical vaccine testing.

In the first stage, the vaccine is tested on a small group of people, to see if it stimulates the immune system response, and if it has significant side effects.

In the second phase, the vaccine is tested on several hundred people, including different groups, such as children and the elderly, to observe the effect on these groups.

If this stage is also passed successfully, then the testing passes to the last stage, in which it is administered to several thousand people. At this third stage, it is determined whether the vaccine has serious side effects, and whether it really protects against the virus to a level that is considered sufficient.

In the U.S., for example, the Food and Drug Administration’s requirement for a vaccine approval is to protect at least 50% of those vaccinated.

There are about 165 groups of scientists registered at the World Health Organization who are working on the development of a vaccine against the novel coronavirus. Only seven of them have reached the third and final testing phase.

The most promising vaccine so far seems to be the one developed in the UK by Oxford University scientists in collaboration with the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneka. The results of the second phase of clinical trials suggest that the vaccine is relatively safe, with no serious side effects. Meanwhile, antibodies that fight the SARS-CoV-2 virus, according to the study, have been activated in over 90% of study participants, which gives scientists hope that the vaccine may be effective.

If this or another vaccine turns out to be successful after the third phase, then mass distribution may be expected to start in early 2021.

However, vaccines alone may not be enough to put an end to the pandemic for a number of reasons.

Firstly, it is still unknown how effective any vaccine will be; experts suggest that in order to create so-called herd immunity — where the percentage of people with immunity is high enough to minimise risk of transmission — the vaccine should have a relatively high efficacy of at least 70 percent.

The vaccine also may not work well in older people, who are most at risk of becoming seriously ill and dying from the disease.

Significantly, it is still unknown if the vaccine will produce long-lasting immune responses. Some initial studies suggest that antibodies in people who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 last only several months. If that is also the case with any vaccine, then the likelihood of achieving herd immunity would be slim.

Ultimately, there still remain many unknowns.

What we do know is that to help Kosovo’s fragile health system from becoming completely overwhelmed we still have to stick to the public health approach: wearing masks, physical distancing and maintaining personal hygiene. For the time being, they remain the only effective means of protection against the coronavirus.K

Editor’s note: At the request of patients and their families, the names in this article have been changed to protect their identities.

Feature image: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

My partner and I stumbled over here from a different website and thought I may as well check things out. I like what I see so now i'm following you. Look forward to looking over your web page repeatedly.