He was hanging up above in the air, detached from the ground, maneuvering a basket on to the crane of a small truck that lifted him and his paintbrushes. For two days Andrej Zikić, an artist from Belgrade, was trying to turn the worn out façade of a building on Myslym Shyri street in Tirana into a canvas for art. The work, a boy with a bicycle thrown on his shoulders, was complete except for some final brushstrokes.

The Serbian painter, whose artistic name is Artez, is one of 13 international street artists who responded to the call of the Tirana Municipality to be part of the first Mural Festival in the Albanian capital in early June.

Tirana’s first Mural Festival saw a number of street artists hanging precariously in the sky as they painted the cities’ façades. Photo: Artan Rama / K2.0.

“Through colors we are trying to send positive messages,” says Director of the Town Hall Decoration Office, Henril Cule. With a small budget, the director also has to negotiate permission to use some of the façades, especially for the first-floor windows owned by citizens who are often skeptical of this type of art.

A few days later, ten more artists were invited to paint murals on to the façades and other objects in the capital. This time the project was being run by the City Promotion Directorate but since they both operate under the umbrella of the Tirana Municipality, the activities were merged into one.

In a city with uncontrolled urban development, street art is rushing to take advantage of an opportunity to gain a safe place and use urban space for direct communication with pedestrians.

A few blocks further, at the entrance to ‘The Commune of Paris’ neighborhood, Licuado from Uruguay is drawing a portrait of a woman on the side of a thin, windowless building. The symbols reveal a pleasing metaphor as the artist aims to turn street noise into street art. “It’s the mother… my mother,” he says. “But she represents all the mothers!”

The mother of Liucado, a street artist from Uruguay, now watches over the city. Photo: Artan Rama / K2.0.

Together with his paints, brush and a small lunch held in a small plastic container, he will stay atop the scaffolding until late. Urban noise fades away in the height, but Licuado hopes that the icon will eventually come down to the street.

Around him, a dense network of brands and Internet cables spread anxiety and insecurity, but there are threads in Her hands, which in a traditional way, as well as a modern way, connect us to the past and the promise of eternity.

“The street inspires me. It fills me with poetry,” says another street artist, Eldi Veizaj. “I adapt my colour to the terrain, just like architects do. Then the painting belongs to you,” he told K2.0. The Town Hall Decoration Office had erected scaffolding near the Grand Park of Tirana, allowing Veizaj to spend three days creating a mural for the city.

Eldi Veizaj’s piece at Tirana Mural Festival worked to complement its natural surroundings. Photo: Artan Rama / K2.0.

His work, “Ave Maria” affirms the natural elements through a feminine portrait. “I tried to break through to the people and so I built a portrait with the colors of water,” he says.

A good concept, I would think. But how does it help us to understand the city and its problems? Can it add to green space, greenery on the façade?! If not, let’s go back to the gallery!

Albania, formerly communist and isolated during the Cold War, is today an open-door city and Tirana Mural Fest is a possibility for authors to climb onto the façade.

Globalism and metropolises are fueling new aesthetics. Materials and techniques have changed. Artists, freed from curators, are expanding their energy. But is it merely an aesthetic that fulfills the unfolding of the artist’s ego?

Let's show problems through the walls, let’s even criticize through them.

A conversation with the man who, together with his team, enabled the festival helps me to understand more. ‘The Town Hall Decoration Office’ sounds like an old-fashioned term but director Çule gives off an altogether different impression. Seeing his arms covered with colorful tattoos, striving to understand his motives becomes easier.

I say to him that colors are not enough. He answers, with certainty, that the walls are not there to solve problems. But, I say to him, let’s show the problems through the walls, let’s even criticize through them. He tells me that so far no artist has asked for such a thing.

I finish the interview, but I’m never satisfied with the questions, even when I like the answers. So I put the colors aside and decide to penetrate the façade.

Nadine Kseibi, an artist with dual Romanian and Syrian citizenship, was assigned to work in the Blloku neighborhood as part of the Mural Festival. But before she started, she removed another poster from the wall, placed there a few months ago.

While the Mural Festival added color to Tirana’s façades, the new works sometimes replaced pre-existing street art, often those with a more political character, including “Sorella Tone” by activist group Çeta. Photo: Artan Rama / K2.0.

The previous work had transformed “Motra Tone,” a famous piece by Albanian classical painter Kole Idromeno, giving her a modern makeover and naming her “Sorella Tone,” a translation from Albanian to Italian, as a comment on the huge number of Italian call centers operating in Albania. It was created by Çeta, a group of activists operating anonymously that has used their creative energies to criticize government policies through graffiti.

Kseibi’s work, “Innocence without identity,” was wonderful, perhaps the best of the festival, but the circumstances under which it was created — removing another achievement and not without the help of the municipality — gave me a sense of frustration.

Nadine Kseibi’s “Innocence Without Identity” was one of the highlights of the festival, but the circumstances in which it was created were controversial. Photo: Artan Rama / K2.0.

In August 2016, the Mayor of Tirana, Erion Veliaj, issued an order on the Rules and Conditions for Using Public Space in the municipality, just a few months after Çeta had started activities.

Çeta’s work is often explicitly political. Another piece featured a transformation of Sali Shijak’s socialist-realist painting of assassinated Partisan fighter Vojo Kushi on top of a tank, repositioning him on top of a Jaguar. Another piece, Mother Zylja, referenced an elderly woman fined by the municipality for selling leeks on the street, while the group also produced a stencil commemorating Arditi Gjoklaj, a teenager who died in controversial circumstances at the Sharra landfill site in Tirana.

Puna me karakter të qartë politik e Çetës përmbledh një seri veprash të cilat bien ndesh me qëndrimin e shtetit shqiptar. Posterat dhe vizatimet e tyre, shpesh janë fshirë prej autoriteteve lokale. Fotot: Artan Rama / K2.0.

Puna me karakter të qartë politik e Çetës përmbledh një seri veprash të cilat bien ndesh me qëndrimin e shtetit shqiptar. Posterat dhe vizatimet e tyre, shpesh janë fshirë prej autoriteteve lokale. Fotot: Artan Rama / K2.0.

Vdekja e 17 vjeçarit Ardit Gjoklaj në vend të punës, nxiti protesta në vend si dhe muret e qytetit ishin mbushur me grafite në të cilat kërkohej drejtësi për vdekjen e tij. Foto nga Artan Rama.

Vdekja e 17 vjeçarit Ardit Gjoklaj në vend të punës, nxiti protesta në vend si dhe muret e qytetit ishin mbushur me grafite në të cilat kërkohej drejtësi për vdekjen e tij. Foto nga Artan Rama.

After the series of works ended, exposure remained a problem. Public space became Çeta activists’ favorite exhibition hall as well as their battlefield with the authorities. Within a few hours or days, images made by Çeta were often hidden or altered.

In just a few minutes, through spray techniques, chalk and posters, activists filled the walls and hidden, under their hoodies, avoided cameras on the street.

One evening, I met three of them. They didn’t tell me their names, but they showed me enough about their subversive action. In a small shelter, with a roof and a yard I developed this chat:

Me: Who are you?

Çeta: A political art group.

Me: What do you mean to do?

Çeta: To provoke, but also to emancipate.

Me: Why are you hiding?

Çeta: To avoid fines and not to put the focus on us, but on the phenomenon.

Me: Who pays you?

Çeta: We work voluntarily.

Me: Who guides you?

Çeta: No one! Decisions are taken as a group.

Me: Why do not you ask permission to stick the posters in public spaces?

Çeta: Because they are public spaces and belong to us all.

They told me they would stay anonymous and that joint work is more important than everyone’s ego.

Puna e Diversantit (Ergin Zaloshnja), me një karakter të theksuar politik, gjithashtu është fshirë, por ai shpreson se numri 13 i fanzinës së tij mund të mbetet në mur. Fotot Artan Rama / K2.0.

Puna e Diversantit (Ergin Zaloshnja), me një karakter të theksuar politik, gjithashtu është fshirë, por ai shpreson se numri 13 i fanzinës së tij mund të mbetet në mur. Fotot Artan Rama / K2.0.

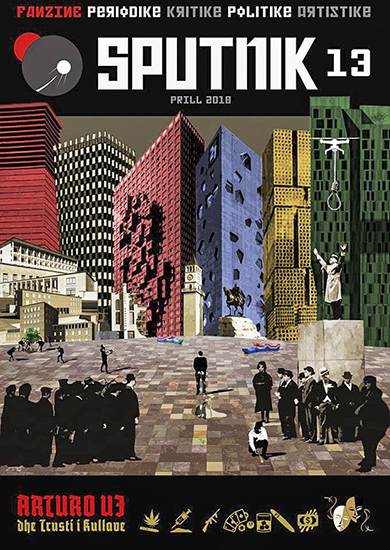

Another street artist, Ergin Zaloshnja, whose artistic name is Diversanti and who created the first wall based fanzine titled Sputnik five years ago, has also had work removed by the Municipality.

For Zaloshnja, hiding has never been a goal, but his fanzine has not had better luck than Çeta. He has pasted twelve poster fanzines on to the walls of the capital, before workers of the Town Hall Decoration Office removed them. But on the outskirts of Blloku, there are traces of his forbidden graffiti, or rather what is left of them…

The thirteenth piece, “The Trust of the Towers,” is expected to be released soon. Let’s see how long it will stay! Regardless, in the eyes of the capital’s consumers, the city’s decorative paints can be seen more clearly than the dark of a dystopian society that Ergini represents.

In efforts to win the hearts of residents, artists and the authorities are using the street to create a new urban aesthetic, one with a message. But beyond their goals, because of different motives, street art is turning more into a battle for the street than for art itself. And the right to public space risks allowing the authorities to make selective decisions, to the detriment of both their opponents and political freedom.

This early summer in Tirana, some of the international artists who ‘occupied’ the façades were really wonderful. But when the effect that is caused by the color comes to a halt, a question arises: Who does the art of the façade serve? Is it an illustration of a trend, or something more than the ego of a contemporary artist?

Tirana is elevating its façades. Let’s give the walls the opportunity to tell the truth, through colors, but also through contrasts, through an action aimed at a collective reaction and not just the egos of street artists.

The “small city decoration office squad,” as Mayor Veliaj labelled them during his electoral campaign, has just started to understand the great weight of decision-making. But do they have the freedom and the opportunity to turn street art into a platform of dialogue rather than a dictatorship?

In a city where street noise threatens to suffocate any sound, façades must be heard and spoken. The Tirana Mural Fest at least shows that they have just begun to stammer…K

Photos: Artan Rama / K2.0.