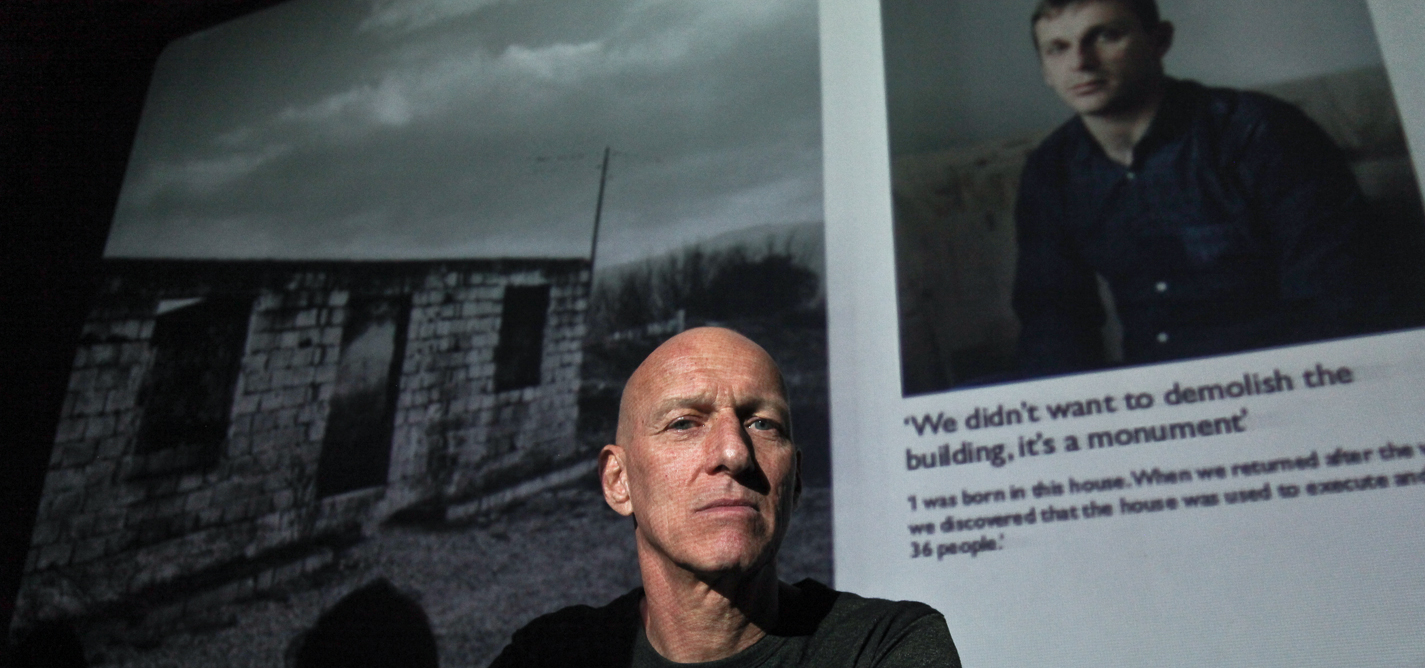

Behind an empathetic lens

Dutch photographer’s Prishtina exhibition inspired by own family history.

“They told me that they had never seen the pain captured like this.”

"I don’t just look at somebody and decide if that person is very photogenic. No, I hear the story and then I think, ‘This is a story that fits into my project, and it’s up to me if I can take a picture.’”

Dafina Halili

Dafina Halili is a senior journalist at K2.0, covering mainly human rights and social justice issues. Dafina has a master’s degree in diversity and the media from the University of Westminster in London, U.K..

This story was originally written in English.