In March, 2020, it was announced that all levels of education would cease operation. The dormitories at the Prishtina Student Center, where about 4,000 students normally reside, would be emptied out.

Soon, as part of the government measures to stop the spread of COVID-19, which had just arrived in Kosovo, the dormitories were used as a quarantine center for those who entered the country from abroad.

Amid all the commotion, the dynamic of the students’ lives changed drastically.

Gazmend Qyqalla, a young Ashkali man who studies at the faculty of education of the University of Prishtina, describes himself as an extrovert who likes to spend a lot of time with people. For him, as well as for many others, immediately shifting from an interactive study dynamic with other students to complete isolation somehow caused him to lose connection with the outside world.

Shukrije Stolla, a student of elementary education, describes her emotional state during this time as “exacerbated” because of isolation, personal issues and the worsening of the economic situation. The dark thoughts that have accompanied her regarding the narrowed perspective for employment in the near future have burdened her even further.

Shukrije is only one of many young people in Kosovo — who simultaneously represent the largest population group and the one with the highest unemployment rate in the country — who are suffering consequences from the pandemic. According to an assessment by UNDP, 12% of youth between 18-24 had lost their jobs up until June 2020.

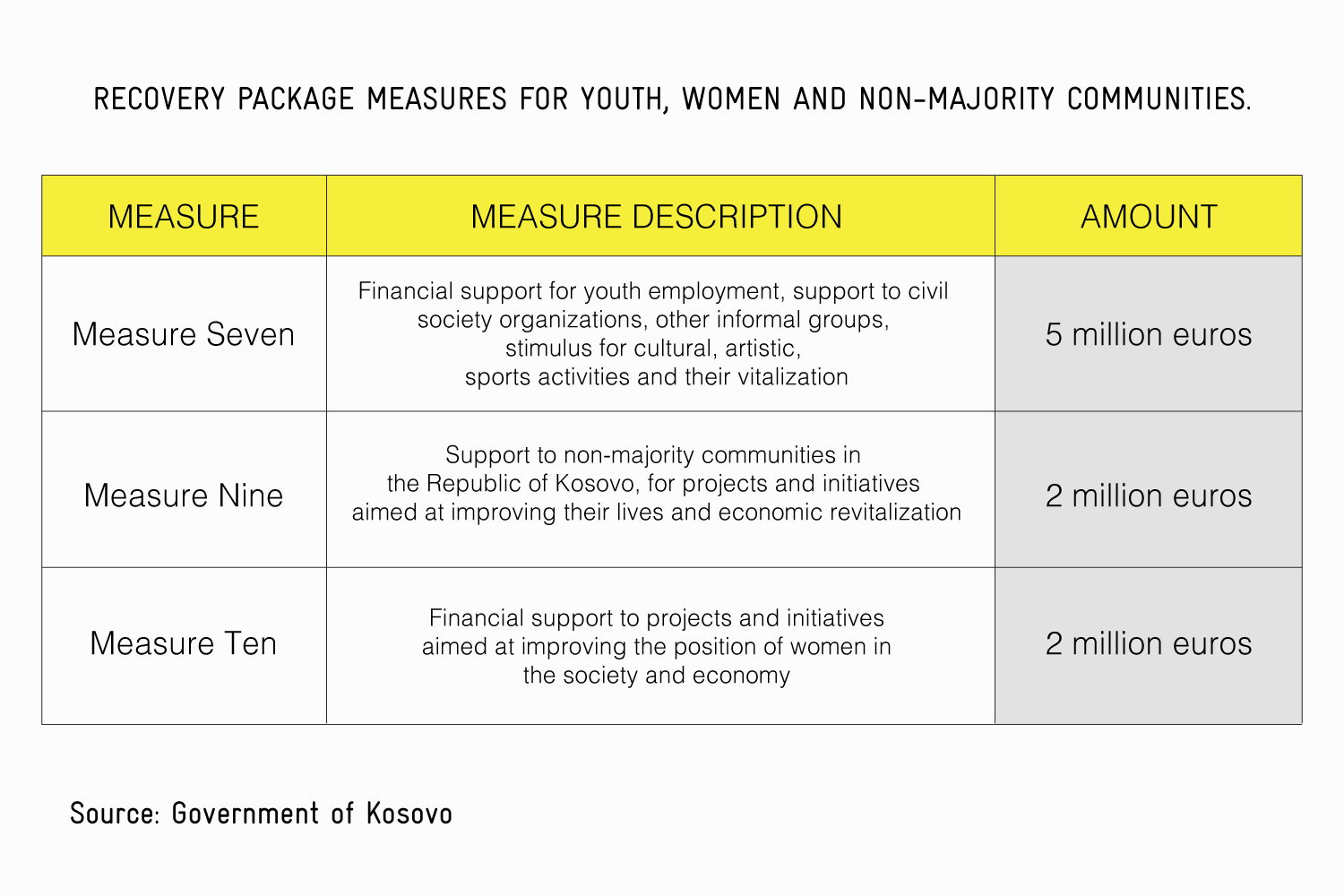

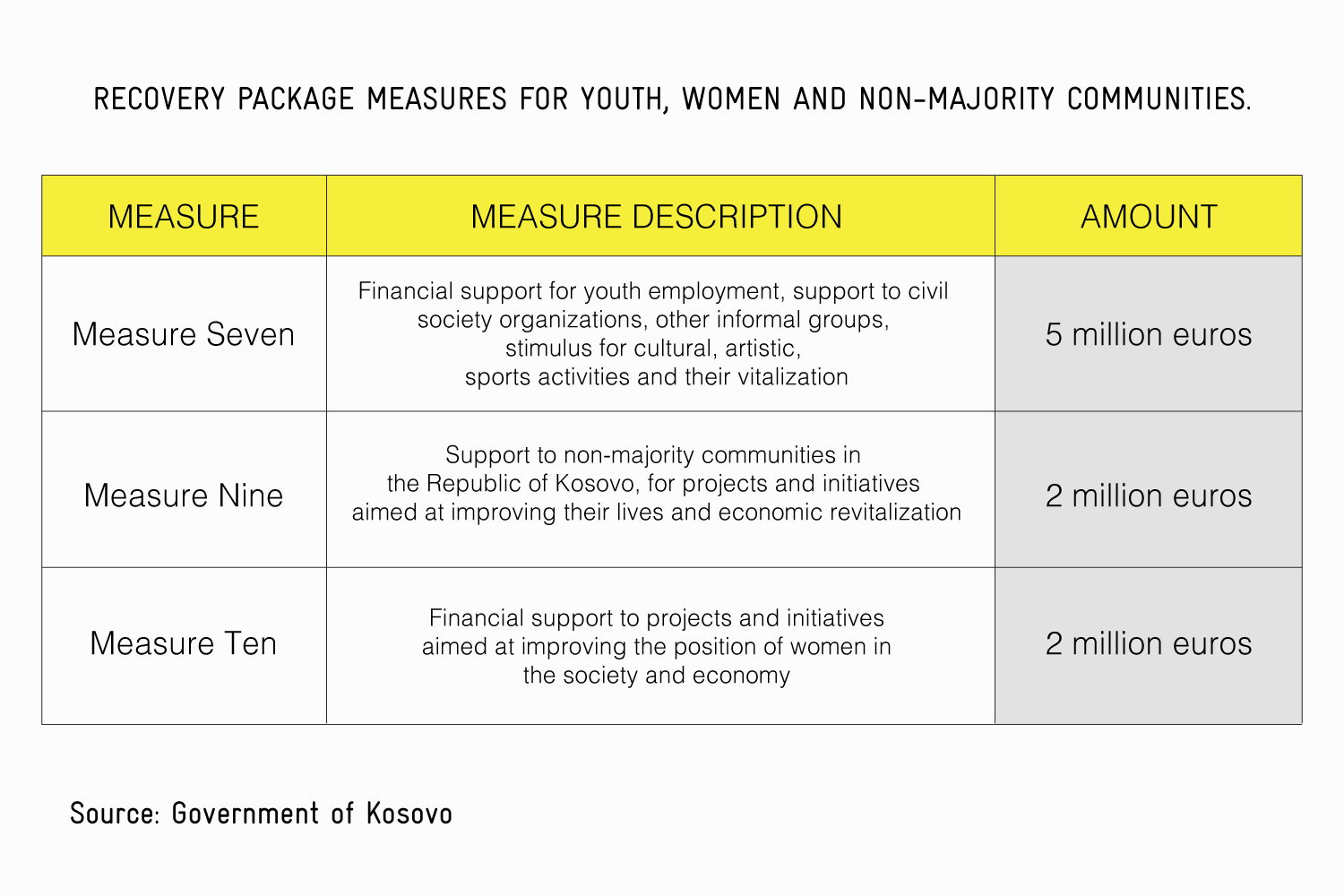

Responding to the economic damage wreaked by the pandemic, the government approved an economic recovery package in August 2020 worth 365 million euros. The package was turned into a law only in December, after a few failed attempts to pass it in the Assembly.

The package stipulates financial support mostly for businesses, but also for other vulnerable groups of the population, including youth, women, and members of the Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian communities.

Although it has now been almost five months after the announcement of beneficiaries of the economic recovery package, there is still no clear and sufficient information by the institutions about the implementation of the three foreseen measures for supporting these groups.

According to an analysis published recently by the GAP Institute, “Inclusion of Women, Youth and Non-Majority Communities in the Economic Recovery Package,” only 400 young people have been supported by measure seven in the form of internships funded by the Ministry of Youth, Culture and Sports at 500,000 euros total.

Regarding measure 10, the Gender Equality Agency has allocated the second sum of 1 million euros this March to small businesses and organizations that work within the community; the first 1 million was allocated in December last year.

Meanwhile, the last notice published by the Office for Communities regarding the implementation of measure nine dates back to October last year and there is still no information on the beneficiaries and the degree of execution of this measure.

To learn about the individual experiences of people who belong to these vulnerable groups, we have spoken to some of them about the institutional support that they have received, or that has been absent.

‘Leftover crumbs’

Nuhi Berisha, a young Ashkali man whose studies are financed by his parents, said that he and his family’s economic situation have taken a hit over the past year. “My family’s income is dependent on crop and animal farming, and there were movement restrictions and market shut down measures,” he explains.

For youth who come from non-majority communities in the country, being discriminated against and pushed away from society is a bitter reality. Difficulties in accessing health care services, education and employment make them more vulnerable to the pandemic than the rest of society, and in various dimensions too.

As far as financial support during the pandemic and toward recovery is concerned, studies in the field attribute the greatest assistance to civil society and international organizations, rather than domestic institutions.

"We as a family do not have a registered business, be it as crop or animal farmers."

Nuhi Berisha, student

Nuhi agrees, saying that he has also been assisted by the Municipality of Fushë Kosova, where he lives. “We managed to do it somehow with the help of the municipality, various NGOs that aid the community, and the diaspora,” he says.

When asked about the government recovery assistance, he explains the layered barriers that have prevented his family from receiving the package’s benefits.

“We as a family do not have a registered business, be it as crop or animal farmers — thus we were unable to benefit from it,” he says. “The taxes that have to be paid for maintaining a business are unaffordable — we don’t profit that much anyway from our work as a family.”

Apart from his studies, Gazmend works as an educator at the Balkan Sunflowers organization, which among others focuses on education and minority issues. He pays a lot of attention to the damage that has been caused to schoolchildren by the disruption of the education system as a result of the pandemic.

According to him, the pandemic year has set pupils back almost a full year because many Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian children have not been able to attend online teaching because they do not have the necessary technological devices. “Although some NGOs tried to distribute technology tools, the number was small because the demand is high,” he says.

Gazmend Qyqalla, educator at Balkan Sunflowers, says that the lack of online attendance by Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian schoolchildren has been very evident. Photo: Agan Kosumi / K2.0.

In all decisions and measures of the government and ministries as part of the recovery package, only measure nine provides for the financing of projects for these communities — there is no other affirmative measure.

In line with the government’s program, the Office for Community Affairs (ZÇK) is the institution responsible for implementing measure nine of the package, which provides for the distribution of 2 million euros in support of non-majority communities.

This office has published a call for non-governmental organizations and small enterprises with three objectives: Providing basic living support for people in need from non-majority communities through food and hygiene packages, mitigating the economic consequences of the pandemic through supporting small enterprises and employment, as well as the provision of psychological assistance to abandoned and sick persons.

The ZÇK did not provide data on where the funds were distributed to the communities.

Meanwhile, Gazmend says that he personally did not receive any help through the package, as he had expected. “We protested in front of the government not to vote for the package because we knew it would not be inclusive for non-majority communities because what usually happens is that the Serb community benefits [more], and the rest is left to other communities.”

Both the relevant measures and the public notice of the ZÇK refer to “non-majority communities” without distinguishing between the Serb community and other communities.

‘To me, this NGO is the state’

Youth and minority communities are not the only vulnerable groups not sufficiently involved by the government in its efforts to mend the damage dealt by the pandemic. Women too, who even before the pandemic were generally at a disadvantage both in the family and in society at large, were severely affected by COVID-19 and did not receive sufficient assistance.

Arta Maliqi Shala, who started a business called Zanart two years ago with filigree and leather handicraft accessories, says the only aid she has received from the state is two deposits of 170 euros allocated to workers in April and May 2020 because of the emergency fiscal package.

During the pandemic she worked from home sewing masks, while she also had to take care of her three children. “No matter what position you have, you have to be the head of the family,” she says, having now begun to return to her initial business and gradually develop it while hoping for subsidies to get her up and running.

According to a survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in Kosovo, out of 166 registered business owners, 68% faced economic difficulties during the pandemic, and about 65% of their businesses were completely or partially closed during the quarantine period in the first half of 2020.

Arta Maliqi Shala says that she expects the state to help her with subsidies so that she can return to working on her business. Photo: Agan Kosumi / K2.0.

In the package for economic recovery, through measure ten, the government has provided financial support for projects and initiatives aimed at improving the position of women in society and the economy, in the amount of 2 million euros.

According to the Agency for Gender Equality, measure ten is directly applicable to the goals of inclusive growth and preschool education. This aims to help strengthen the position of women in society, knowing that the burden of caring for children and the elderly falls mainly on women, so increasing the inclusion of children in preschool education may help women become more likely to be included in the labor market.

The package does not help women who work in the informal sector.

The first group that has benefited from this measure are the private preschools and kindergartens registered as NGOs, with 1 million euros. According to the GAP Institute report, since 1 million euros have been allocated to help preschools, they are earmarked for rents and operating costs and thus do not help the women affected by the pandemic to recover economically.

According to the GAP report, the low level of activity of women in the labor market, the high unemployment rate and the high number of women working without contracts make it impossible for most of them to benefit from this measure. Among the main problems is that the package does not help women who work in the informal sector.

Mimoza*, a single mother raising her only son, worked as a dishwasher before the pandemic. She says she has been fired many times because of the time she has to devote to her son who suffers from epilepsy.

During the pandemic, she says that the only help offered to her were two food packages from the Municipality of Prishtina, while she survived the entire pandemic year with the help of good Samaritans who provided her with food, as well with the support of the charitable organization “Nëna dhe Fëmijë të Lumtur” (Happy Mothers and Children) where she herself is a volunteer.

“To me, this organization is the state,” she says.

Gresa* is registered with the same organization to receive assistance with clothing and food packages. She is a single mother of five children who during the pandemic could not continue her work as a cleaner and the only help she received were food packages from the municipality.

However, she continues to hold on and not lose hope, saying: “I am responsible for my children and I cannot turn my back on them.”

‘A virtually insurmountable crisis’

Edita Dula, founder of the “Happy Mothers and Children” organization who maintains it with the help of two volunteers working part-time, says that during the pandemic, the demand from women for food, medicine and children’s clothing has increased.

Out of 750 people registered in this organization, 300 are single mothers. “We need to remove some because we have no space for them,” she says. During the interview at the organization’s facility, women would continuously come and ask to be registered, while the answer of the volunteers was: “We cannot do it — you can come and get clothing every Friday, but we do not have food packages.”

In the absence of support from the government, Edita Dula and her organization offer as much help as they can to women. Photo: Again Kosumi / K2.0.

“Here is where they set their hope — they clothe their children for school, get food, medicine, and we offer courses,” Dula says.

She has called on private daycare centers to accept at least two children of single mothers registered with the organization, but she says that she always encounters resistance. “Let them calculate what is left over from others, he or she is fed — they have no other expense but food,” she nonetheless appeals.

The pandemic has caused sudden unemployment and increased the housework that women usually do, has also created a serious crisis for single mothers especially who for several months have had children at home learning online. What’s worse, they are completely excluded from the economic recovery package.

The representative of the NGO Single Parents, Arjeta Gashi, who is a single mother herself, expresses deep disappointment that she has not received any help for her and her child. “Single mothers have seen this as an almost insurmountable crisis,” she says.

Unlike Kosovo, the neighboring state of North Macedonia in government measures adopted in June and December has included one-time assistance for single parents in the amount of 100 euros. Such help, or any other kind of help is needed according to Arjeta, and would help single mothers overcome the crisis that has been deepening for over a year now.K

Editor’s note: The names of the two single mothers have been changed to protect their identity.

Feature image: Agan Kosumi / K2.0.

This article is produced as part of the Mentorship Program within the EU-funded project “Citizens-engage!”, implemented by Kosovo 2.0 in partnership with GAP Institute. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Kosovo 2.0 and GAP Institute and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.