August 22 is the expected date for the approval of the motion to dissolving the Kosovo Assembly, which will open the way for the announcement of snap elections within 45 days. The elections come after the resignation of prime minister Ramush Haradinaj on July 19, and the unwillingness of parliamentary political parties to create some other government majority that would continue the mandate to the culmination of its legal term in June 2021.

Although officially the electoral campaign has not yet begun, political parties have already started their political activities in the field. Compared to the 2017 election, the political landscape seems even more fragmented with the creation of four political poles (LDK, LVV, PDK and AAK) that will seemingly have a difference no greater than 7% between one another. As for other parties, it seems that Nisma is the only one that will reach the 5% threshold, whereas support for PSD and AKR is below the election threshold.

In this situation, the next parliamentary elections will determine the governance trajectory in Kosovo. More concretely, they will determine whether we will continue to implement the existing model that was installed by PDK in 2007. This model, according to recent reports by the European Commission and other international organizations, has made for a situation in which the state has been captured, the judiciary is controlled by the people in power, and monopolies in the economy have been created. Alternatively, will this year’s snap parliamentary elections present an opportunity to change the governance course, to implement one that is based on transparency and accountability? But in the current political context, how likely is it that we will see radical changes in the model of governance?

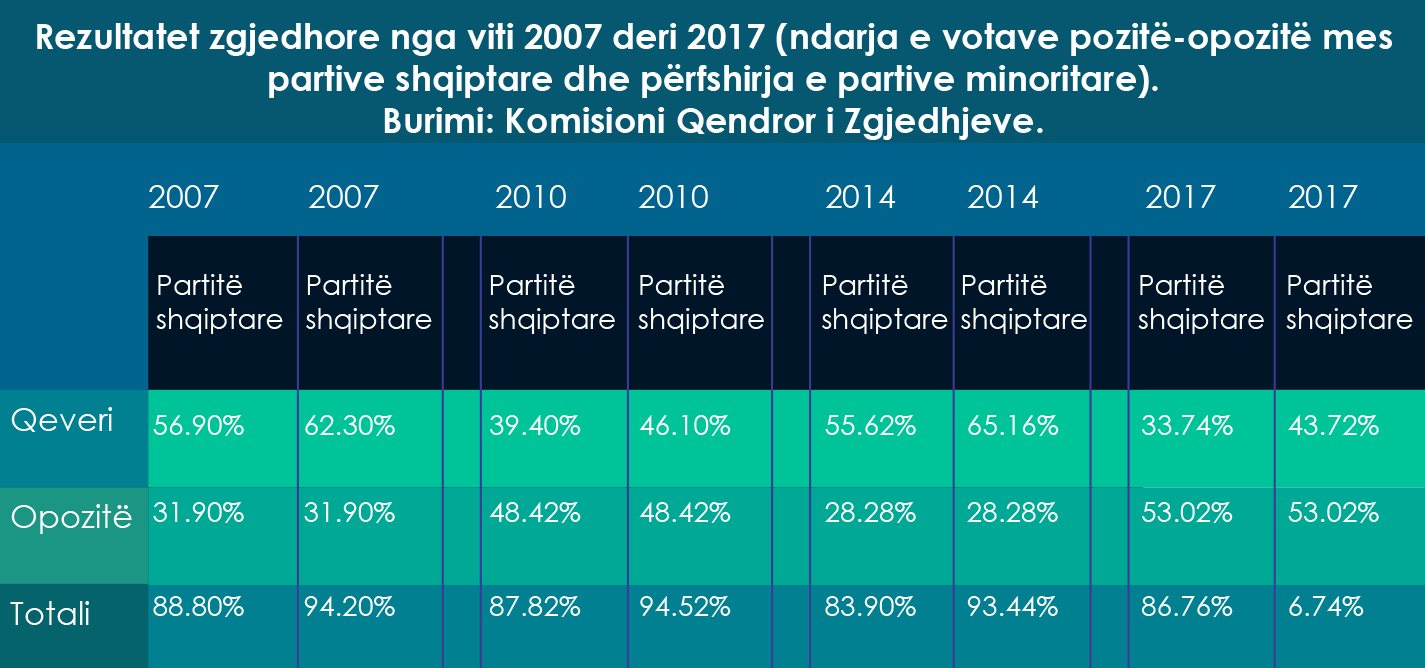

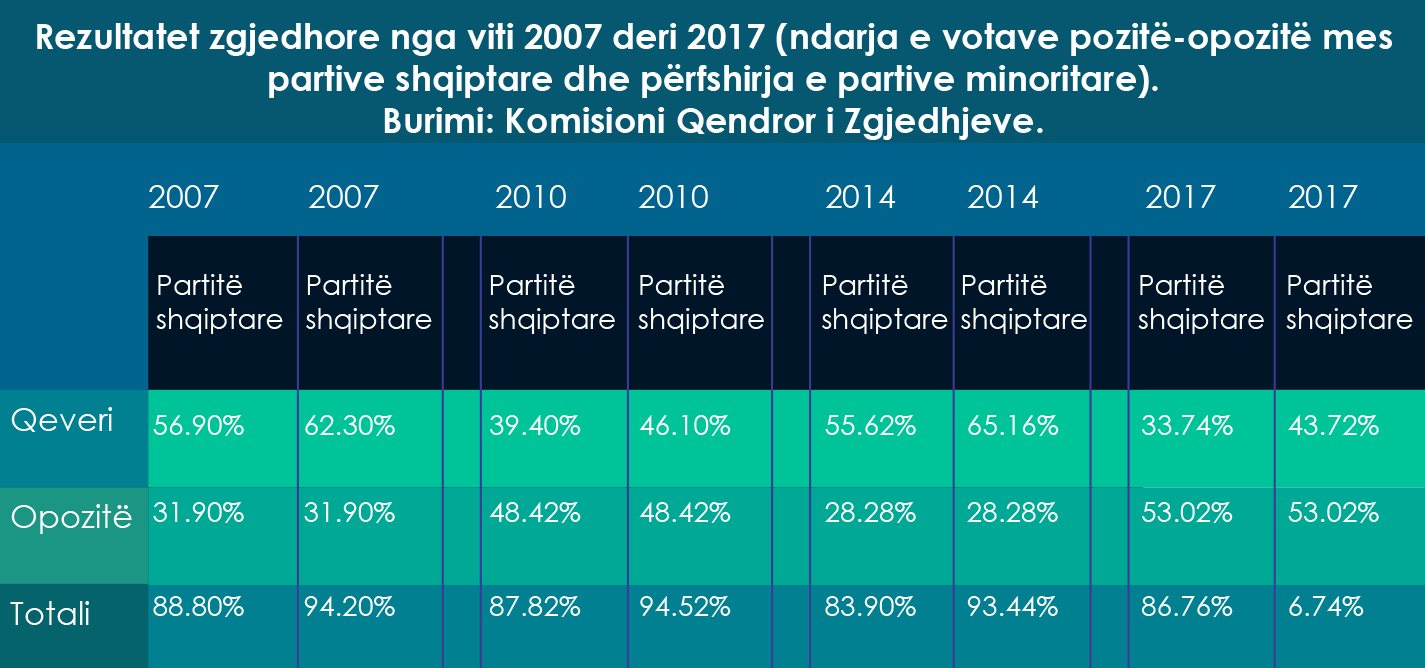

Based on parliamentary election data from 2007 to 2017 (shown in the table below), we can identify a series of conclusions.

Election results from 2007 to 2017 (the division of votes between Albanian parties in the government and opposition, as well as including minority parties). Source: Central Election Commission.

From 2007 onwards, every other election cycle has produced a government with a two-thirds majority of deputies. Compared to compositions in the past, the composition of the Kosovo Assembly in 2017 was the most representative of the votes, with 96.74%. Elections in 2010 and 2017 produced a minimal government majority that didn’t have the support of the majority of voters in Kosovo. In 2010, the government majority represented 46.1% of voters, while in 2018, the percentage was only 43.72%. This represented the lowest percentage of voter support for the government majority since 2001.

In the last four parliamentary elections, the percentage of votes for Albanian parliamentary parties was around 84-89% of the general electorate. The percentage of votes of minority parliamentary parties has risen from 3.4% to 6.6% in the last elections in 2017. Meanwhile, political parties and election initiatives that do not reach the election threshold represent 3-7% of the body of voters on average.

Can extraordinary parliamentary elections change the representation in the Assembly?

If we consider the results of surveys conducted by international organizations that work with political parties, and if the five main parliamentary parties run alone (without pre-election commissions), their ranking is expected to change in the snap parliamentary election.

LDK is expected to receive 24-26% of the votes, which translates to 26-28 deputies. Despite frequent statements from LDK representatives regarding a significant increase in the level of public support for their party, an eventual victory would not see the party very far off from the others. On the contrary, the results represent only a small increase compared to results in 2017, when LDK received 25.53% in a pre-election coalition with AKR and Alternative.

On the other hand, despite the departure of a few members of its parliamentary group in 2018, LVV is expected to receive 22-24% of the vote, which translates to 24-26 deputies. This result will increase LVV’s level of representation in the Assembly, although the election result will be worse compared to the 2017 election, when LVV received 27.49% of the vote alone.

PDK is expected to receive 20-22% of the votes, which translates to 22-24 deputies. This result will be a testament to the drastic decrease in the level of support of voters for PDK, which was not notable in 2017 due to the formation of the PAN coalition. This is expected to be PDK’s worst election result since its establishment, since for the first time electoral support for the party will fall under 25% (including the 2001 and 2004 elections).

AAK is expected to receive 15-18% of the votes, which translates to 17-20 deputies. Support for AAK is expected to increase drastically due to their populist policies, with almost double the votes compared to the 2014 election, when they received 9.54% of the votes. It seems that AAK has managed to attract a considerable number of former PDK voters.

The Social Democratic Initiative (Nisma) is expected to receive 5-6% of the votes, which translates to 6-7 deputies. This result reflects the maintenance of Nisma’s electoral strongholds and is a testament to the electoral stability of the party.

Coalition for a change of governance or just a change of government?

Due to the electoral system and the fragmentation of political representatives into four political poles, it is unlikely that one of the parties will manage to form a government on their own in the near future. As such, coalitions between political parties, formed before or after the election, are inevitable for the formation of the government.

After the election, will political parties continue the practice of political bargaining and the “hunt” for deputy votes so as to create a government majority that goes against the will of the voters? Or will they attempt to form pre-election coalitions with parties with which they manage to agree on future governance priorities?

If we take the above-mentioned election results for granted, then we can expect the following developments regarding post-election coalitions:

- Like in the 2007 and 2014 elections, the 2019 election can produce a government with a two-thirds majority of deputies. In today’s context, this can only be achieved if two of the four main parties manage to form post-election coalitions with the support of Nisma and all other parliamentary parties of minority communities.

- As such, if Nisma runs alone and manages to reach the election threshold, it will play the role of “kingmaker” in the formation of such a majority. Reaching the election threshold as an individual party gives the party leverage in negotiations to form a new government.

- It seems that LDK is in a more favorable position to lead the government, because it can form post-election coalitions with all parties except the PDK. LDK’s potential post-election allies are Nisma, AAK and LVV.

- On the other hand, LVV does not have many alternatives for post-election coalitions. LVV refuses to form a coalition with PDK, but can form one with LDK and Nisma. This will undoubtedly limit LVV’s leverage in negotiations for a post-election coalition with LDK and Nisma, because the latter two parties also have the opportunity to form a coalition with AAK. However, LVV does have its advantages because it can offer LDK the opportunity for long-term political cooperation, which could change the manner of governance and the political scene for the coming decades.

- PDK seems to be in the most difficult position, because half of the Albanian political block (LDK and LVV) have ruled out the idea of forming a new government with them after the election. AAK and Nisma have not yet rejected such a possibility. So PDK’s only option to remain in government is to recreate a PAN 2 coalition after the election. So it is very likely that PDK will return to parliament as an opposition party.

- Although it is expected that AAK will increase its representation in the Assembly, its alternatives for becoming a part of the new government are tied to the LDK and PDK. Due to their aggressive manner of governance from 2017 to 2019, as well as the increased international isolation, AAK could be left out of post-election coalitions. If it goes back to being an opposition party, AAK could radicalize its position concerning the negotiation process with Serbia, and continue the trend of cannibalizing PDK’s electoral base.

It seems that what will determine the winner of the extraordinary parliamentary elections, among other things, is the ability to form pre-election coalitions with as many initiatives and parties that do not have the chance to reach the election threshold. The main political parties that reach these political agreements could win an additional 2-4% of votes. Although this might seem like a small percentage, the weight of it is extraordinary when we consider that the difference between the first and third party may not be more than 5%.

The 2019 extraordinary election will be different from the one in 2017 due to the electoral influence of the departure of the youth in the last couple of years. The fact that these youths will not take part in the election is expected to negatively influence the election results of opposition parties.

Ultimately, the 2019 election is expected to produce the next paradox in the local political scene. Despite the PAN coalition’s misrule, in general they are expected to receive more votes, 42-45%, compared to their result in in 2017, which was 33.74%. So Kosovar voters will “award” the PAN parties, despite their misrule. Moreover, voters are expected to “condemn” one of opposition parties, since their general percentage is expected to fall from 53% to 50%.

With these potential election results, which impose the creation of a government coalition of more than two big political parties, it is difficult to expect drastic changes in the governance model. The formation of such coalitions will be followed by compromises regarding government objectives and the purity of the future composition of the government, which will limit the space for brave decisions in the battle against crime, corruption and monopolies.

Feature image: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.